Another year in tennis is winding down, although you might think otherwise when stories about Björn Borg and Boris Becker are still making headlines in the UK. It has often been observed that, while the British nation collectively is not very interested in the game of tennis, it really is rather deeply invested in any homegrown players who might show promise, as well as the fortnight-long All England Wimbledon Championships, known to most of us simply as Wimbledon.

The singles champions this year were the Polish woman Jadwiga “Iga” Świątek and the officially Italian but ethnically Austrian (ie German-speaking South Tyrolean) Jannick Sinner. As is traditional, the two winners danced together at the Wimbledon champions ball.

Some of the vocabulary associated with tennis is a little on the opaque side, and includes a number of English-language words which have been borrowed from French. This happened because the sport has some of its roots in a French precursor game called jeu de paume “palm game”, referring to the palm of the hand, as it was originally played without racquets. Also, French was the lingua franca of the European aristocracy, who were the people with enough wealth and leisure time to indulge in sporting activities during the early days of the development of the sport.

The name of the game of tennis itself came from Anglo-Norman French, where the instruction “tenetz!”, literally “hold, receive, take!”, indicated that a player should get ready to receive the ball.

Other tennis vocabulary is also medieval French in origin. “Deuce” is derived from Old French deus, modern French deux “two”. It denotes a rather complicated concept – a situation where two players have each won three points in a game (called 40 points), in which case one of the players must win two successive points to win that game.

Suggested Reading

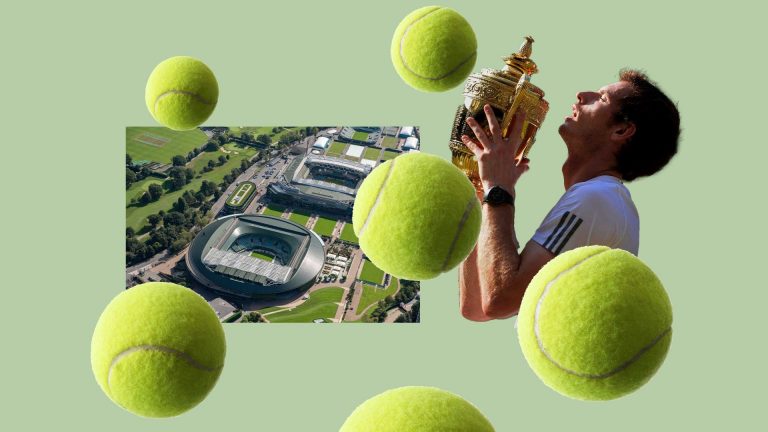

Nerd’s Eye View: 14 things you need to know about Wimbledon

“Love” is the specialised tennis term for nought or zero, but nobody is very sure about where this usage comes from. Some people have argued that it originates in French l’oeuf “the egg”, assuming it was a jocular way of referring to the similarity between the form of the numeral 0 and the ovoid shape of a duck’s egg. The same analogy also can be called on as the source for the cricketing term “duck”, meaning a score of zero as in “he was out for a duck”, which we can assume is short for “duck’s egg”.

On the other hand, the term “let”, in its meaning of a stoppage or obstruction, is an entirely English word from Germanic stock; it is now obsolete except in legal documents, where it is found for the most part only in the fossilised phrase “without let or hindrance”. A let in tennis refers to a serve which catches on the net and therefore slows down, but is not stopped by this hindrance. When this occurs, the rules of the game state that the serve should be replayed, so as to avoid giving the server an unfair advantage.

The etymology of “racquet” is not at all certain, but it seems that the word also came into English via French, from Old French rachette, which, ironically, was the name of a game in which the ball was hit with the palm of the hand. It has been suggested that the word originates in Arabic rāhat, grammatically derived from rāha “palm of the hand”.

Fortnight

Fortnight meaning “two weeks” is an ancient word that is a contraction of “fourteen nights”. The word is rarely employed by Americans and indeed is not even understood by many of them. Its companion word sennight “week”, from “seven nights”, is now unknown even to most British speakers.