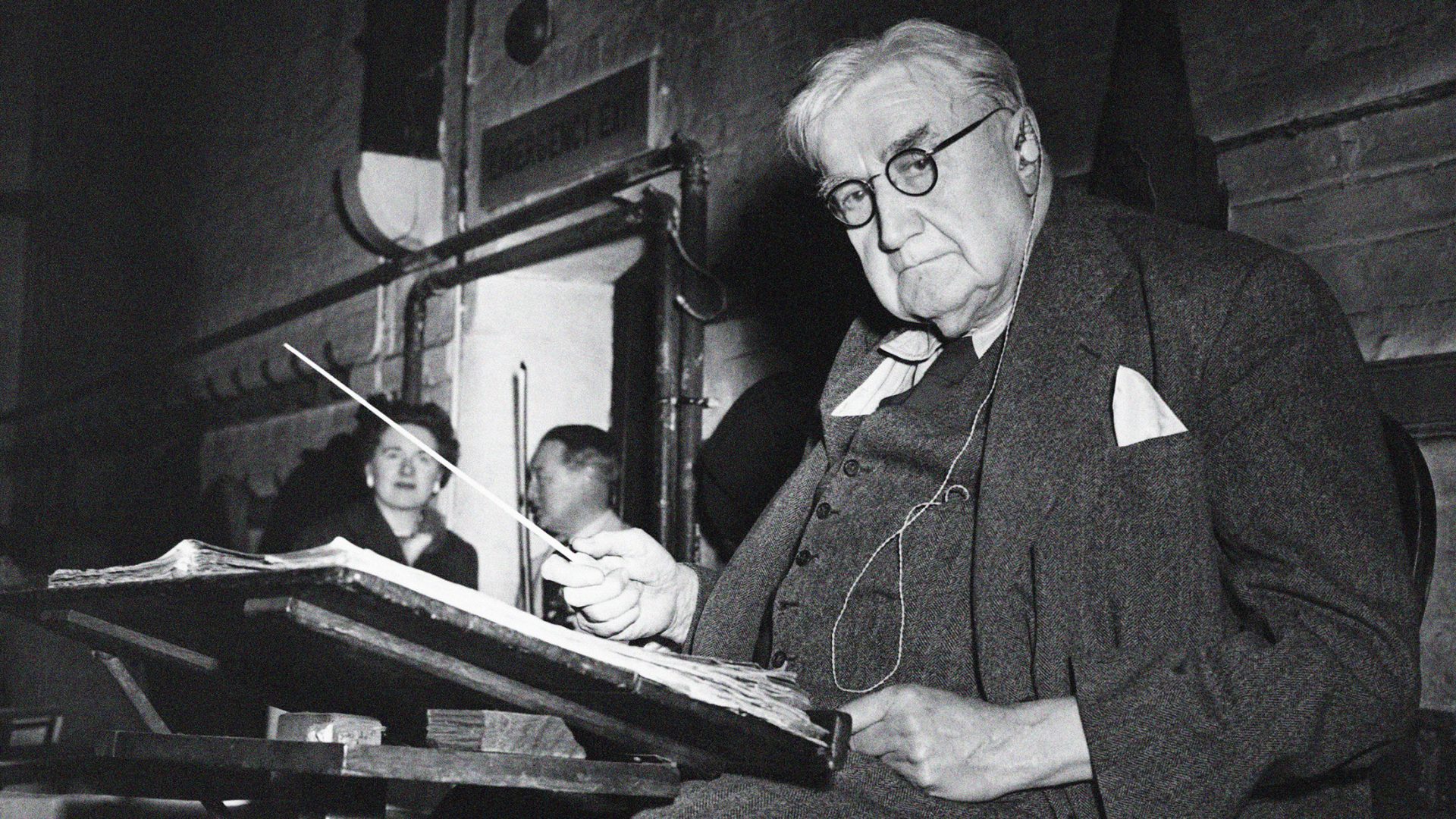

Classical music aficionados who read this column will probably be very familiar with Ralph Vaughan Williams’s 1910 orchestral piece Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, which was one of the first works to gain him international recognition as a composer.

Like Vaughan Williams, Thomas Tallis himself (1505-1585) was also an English composer. His compositions were primarily vocal and choral, and he is still considered to be one of England’s greatest composers.

But there is considerable evidence to suggest that these same aficionados may be rather less familiar with how to pronounce the name of Vaughan Williams’s piece itself – specifically, how they should say the word Fantasia.

This term first appeared in English in 1724. It was a borrowing from Italian – as is the case with so many other musical terms, ranging from allegro to vivace. It unsurprisingly means “fantasy”, and in the context of music it refers to “a composition in a style in which form is subservient to fancy”.

Suggested Reading

Becoming vexed by vanishing vocabulary

Until the 1940s, people in Britain were not in any doubt about how to pronounce fantasia: they pronounced it as best they were able to in the Italian manner (entirely reasonably given its Italian source), with the emphasis on the penultimate syllable – fantas-EE-a.

The word ultimately goes back to Ancient Greek, where phantasía meant “an act of making something visible”, from the verb phantazein “to make something visible”, from phanein “to show”. The Ancient Greek word survives in Modern Greek as phantasía, which is probably now best translated into English as “imagination”. The Modern Greek verb phantázomai means “I imagine”.

The current English word fancy functions in a very versatile way as a noun, as in “to take a fancy to”; as a verb, as in “I fancy a coffee”; and as an adjective, as in “fancy dress”. It first appeared in written English in the 1500s, and is in origin simply a reduced form of fantasy, although the meanings of fancy and fantasy have diverged rather considerably over the centuries, just as the spellings have also changed.

But then in a highly unusual development, external forces intervened in the history of the pronunciation of the word fantasia. These external forces arrived in 1941, emanating from the California studios of Walt Disney, who in that year released a highly innovative film – or movie as younger British people now say – called Fantasia, which took the form of animated cartoons set to eight different pieces of classical music. These include Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue for Organ in D minor, Tchaikovsky’s Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy from the Nutcracker Ballet Suite, and perhaps most famously the French composer Paul Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, with the cartoon animation to the piece starring the famous Disney character Mickey Mouse.

The orchestral score for the film was recorded mostly by the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of the English-born conductor Leopold Stokowski. When the film first arrived on these shores, it came complete with the American pronunciation of its title, which puts the stress on the second syllable. And since then, “fan-TAY-sia” has become increasingly popular as a way of pronouncing the word, even on the part of some of the BBC Radio 3 classical music announcers.

Movies

When I was a teenager, when we went to the cinema, we said we were “going to the pictures”. Pictures was a truncated form of the American phrase “moving pictures”, which the Americans themselves would truncate in the alternative way as movies. It has now become very common over on this side of the Atlantic to use the word movies too.