In 1932, my mother had to leave her North Norfolk village school to go out to work, at the age of 14. My grandfather was a farm labourer, so the family income was not sufficient to keep her and her two brothers on at school for any longer than that.

This meant that she had no opportunity to study any foreign languages formally, something which she greatly regretted and tried to rectify as best she could as an adult by, among other things, borrowing appropriate German course-books from our local library. But she did know at least one French word which, it turned out, the rest of our immediate family had no knowledge of, including my father, who had stayed on at his city school until he was 16 and had studied some French.

This one French item which Mum knew and the rest of us didn’t was largesse, which can be translated into English as “generosity”. When it is found in English-language texts it can also be spelt “largess” without the final letter e.

The reason my mother and other country children of her generation knew this word was because, as the Rev. Robert Forby tells us in his 1825 book The Vocabulary of East Anglia, it was used to refer to “a gift to reapers in harvest. When they have received it, they shout thrice, the words ‘halloo largess’.”

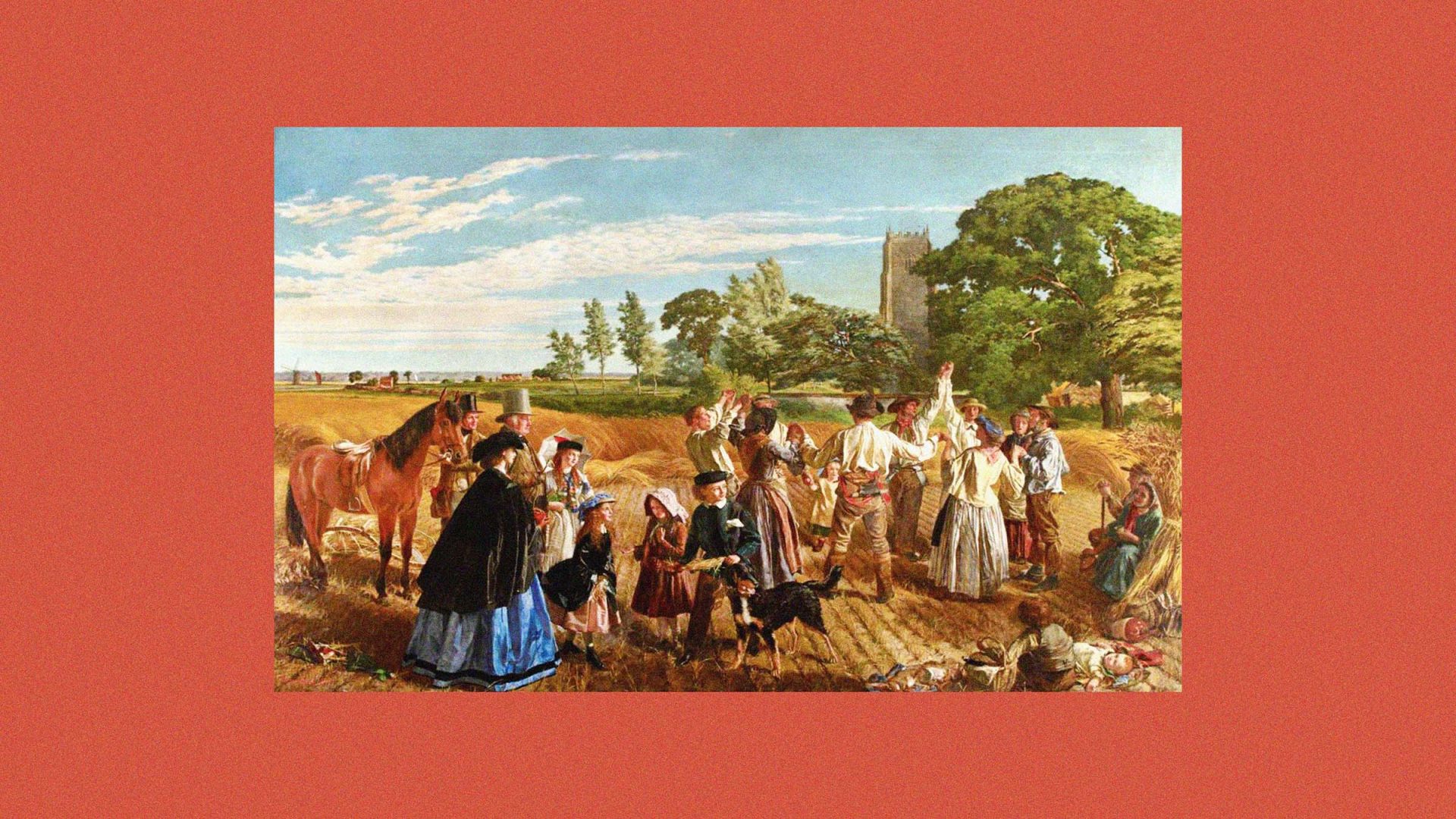

Scotney Castle in Kent exhibits a painting called Hullo Largesse, a Harvest Scene in Norfolk by William Maw Egley, an artist who had been a guest at Reedham Old Hall in Norfolk in 1860. Apparently, anyone staying at an East Anglian farm during the 19th century was traditionally obliged to give harvesters a present or “largesse”, which they acknowledged with the cry “Hullo largesse”.

Suggested Reading

The Gaelic roots of a French football star

When describing this practice, my mother always pronounced the word in the quasi-French manner with the stress on the second syllable, largESSE. She and the other children would run alongside the farm-workers’ horse-drawn carts, and coins would be thrown down to them.

The Oxford English Dictionary writes that “(a) largesse!” was a call for a gift of money, which used to be addressed to a person of relatively high position on some special occasion, such as a royal coronation, but also the annual harvest.

The word largesse first appeared in English around 1200. It comes from Old French largesse or largece “a bounty, munificence”, from Vulgar Latin largitia “abundance”, itself from Latin largus “abundant, copious, plentiful; bountiful, liberal in giving, generous”. This is also the source of Spanish largueza, Italian larghezza, as well as of English “large”.

The subtitle of the Rev. Forby’s work was “An Attempt to Record the Vulgar Tongue of the Twin Sister Counties, Norfolk and Suffolk, as it Existed in the Last Twenty years of the Eighteenth Century”. From 1759 to 1825, Forby was the vicar of Fincham, a village which is about 10 miles south of King’s Lynn and 34 miles west of Norwich. Forby himself came from Stoke Ferry in the West Norfolk Fens, close to the border with Cambridgeshire, and was a student for a while at Caius College, Cambridge.

Largesse is now no longer distributed to reapers in this way. The mechanisation of farming, of course, means that there are no reapers to distribute largesse to.

Vulgar

The most usual contemporary meaning of vulgar in English is probably “making explicit and offensive reference to sex or bodily functions; coarse and rude”, but the etymology of the word goes back to Latin vulgaris, which signified “belonging to the lower classes of society, ordinary, common to or shared by all’”.