It is far too early to be sure that Reform will challenge for power at the next election; but not too early to predict that it might – and therefore not too early to consider how to thwart it. What is to be done?

Let us start with the way things are at the moment. First, Labour owes its landslide victory last year to the split in the right-of-centre vote. For example, Labour’s Allison Gardner won Stoke-on-Trent South with just over 14,000 votes. The defeated Tory and Reform candidates won more than 22,000 votes between them. Had there been a single right-of-centre candidate, Gardner’s majority of 627 would have been wiped out. Altogether, Labour won 144 seats with fewer votes than the combined Tory and Reform total.

Lesson number one

Labour needs both Reform and the Tories to remain in business. Destroying either could hand a shedload of seats to the surviving party of the right. This would wreck Keir Starmer’s chances of remaining prime minister.

Also, Labour has lost far more votes in the past 12 months to its progressive rivals than to the right. This month’s YouGov polls show that Labour has retained the support of 63% of those who backed the party last year. This is where the other 37% have gone: progressive parties 24% (Liberal Democrats 14%, Green 8%, SNP/PC 2%); right-of-centre parties 12% (Reform 9%, Conservatives 3%); and others 1%.

Lesson number 2

Labour must beware its flank. It hopes that progressive voters will end up returning home in the key marginal seats, in order to prevent a right-wing government. But Starmer can’t afford to take them for granted.

Suggested Reading

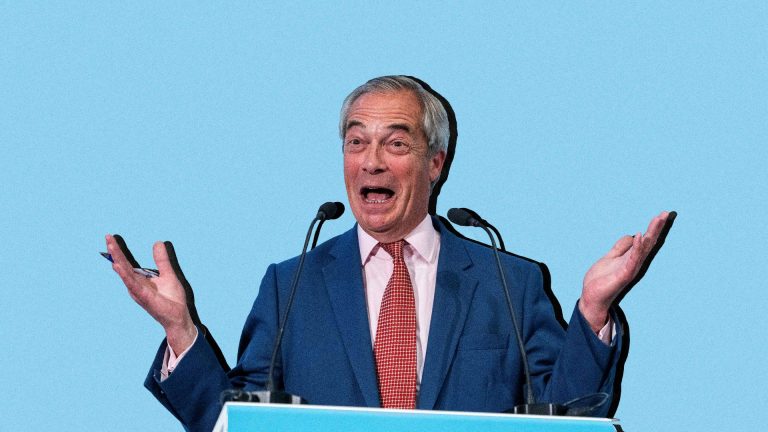

Will Farage be prime minister? Really?

Nigel Farage’s Reform currently outscores Labour by two-to-one among C2DE, working-class voters. Labour used to dominate working-class constituencies, but then came Brexit, Boris Johnson, and Labour’s loss of red wall seats to the Tories. Reform has now picked up many traditional Labour supporters who switched to the Tory Party six years ago.

Lesson number 3

Labour would be well on the way to remaining in office if it could win back these past supporters.

There is little Labour can do to keep both the Tories and Reform alive except, perhaps, concentrating its attacks on the stronger party if its weaker rival seems to be drifting towards death’s door. The challenge is to apply both lesson 2 (win back disappointed progressives) and lesson 3 (woo the former Labour voters who defected to the Tories and now back Reform). Can Labour do both, or must it choose which to prioritise?

If a fresh general election were to be held this year, Labour would be in trouble. It would have difficulty devising manifesto promises on immigration and Europe that could appeal both to Reform voters and defectors to the Greens and Lib Dems. Time is needed to develop a plan that has a chance of appealing to both.

Fortunately, Labour has time. With its big majority it has four years to get this right. By 2029 it will need two things: a record the government can defend, and future policies that are credible.

On immigration, we know that the main concern for most voters, including Reform voters, is control. Complaints about rising overall numbers are rooted in a belief (exaggerated: but perceptions trump truth at election time) that Britain is being flooded with vast numbers of people we have been unable to keep out and don’t want. At the same time, most of us (again including Reform voters) want to admit the people we need to make our lives better: nurses, doctors, care-home staff, engineers, fruit-pickers, plumbers, electricians, waiters and so on.

The key thing for Starmer is to be able to say in four years’ time, “We have stopped the boats and dealt with the asylum seekers who are hanging around with their future unresolved. At the same time, we have positively welcomed those who are fleeing persecution and have a contribution to make to Britain’s future. We should be proud of our record of making strangers our friends. We have also caught those who come here to live under the radar in the cash economy without paying their taxes or enhancing British society.”

If Starmer has achieved those things by then, he has the opportunity to create a consensus around effective action that embraces most progressives and most Reform supporters, and marginalises the minorities on both sides who wish to admit either everyone or nobody. But without a record of achievement, he is bound to alienate his target voters on the left or right, and possibly both.

Much the same applies to Europe. By a consistent margin of more than three-to-two, voters tell YouGov that we were wrong to leave the EU. And by more than two-to-one they tell Opinium that we should now rebuild our bridges to Brussels, either rejoining the EU (34%) or seeking a closer relationship while remaining outside (25%). Far fewer voters want either to leave things as they are (16%) or have a more distant relationship (12%).

So buyers’ remorse has set in, not least on the right. Those who voted Tory last year are evenly divided between those who want bridges rebuilt (46%) and those who don’t (45%). Reform voters are more pro-Brexit, but even here as many as 31% favour one of the two bridge-building options. Once again, if Starmer can point to clear evidence of the benefits of a close relationship with the EU, he has a chance to satisfy, or at least stop annoying, target voters on both the left and right.

However, while four years is a long time in politics, it can be a short time in economics. Starmer needs to act more urgently to bring down barriers to trade with the EU if the benefits are to feed through to extra jobs and greater prosperity by 2029.

One final point. The worst thing Labour can do is tack to the nationalist right. Its message is likely to backfire if it says Reform is raising legitimate concerns, but goes too far. If that’s the choice, then a chunk of Labour’s target voters – the only doubt is how big a chunk – would turn away and decide that they prefer full-fat Farage to semi-skimmed Starmer.