So that’s it. Nigel Farage would become prime minister if an election were held this month. Reform is miles ahead in the polls. More importantly, it would win enough seats either to secure an overall majority or dominate a minority government.

Fortunately for the rest of us, there will not be an election this month. It could well be almost four years away. Past experience tells us that much can change in that time. What more recent experience suggests is that the arithmetic of elections has changed from the days when two main parties carved up most of the vote and competed for power – days when the relationship of votes to seats, though skewed, was reasonably predictable. We cannot rule out either a collapse in Reform’s prospects – or Nigel Farage becoming prime minister in the teeth of the bitter hostility of most voters.

For progressive voters, the joy of last year’s election result came with a stark warning. If Labour could win a landslide with just 35 per cent support in mainland Britain, might Reform do the same next time?

However, there would be one big difference. Last year, voters wanted the Tories out. Keir Starmer was the only plausible alternative to Rishi Sunak. Head-to-head polling showed that voters preferred Starmer by three-to-two. His victory was at best lukewarm, but few people regarded that fact of his arrival in Downing Street as a democratic outrage. Farage enjoys no such lead over Starmer or even Kemi Badenoch today. On current polling numbers a Reform victory would be both likely and outrageous.

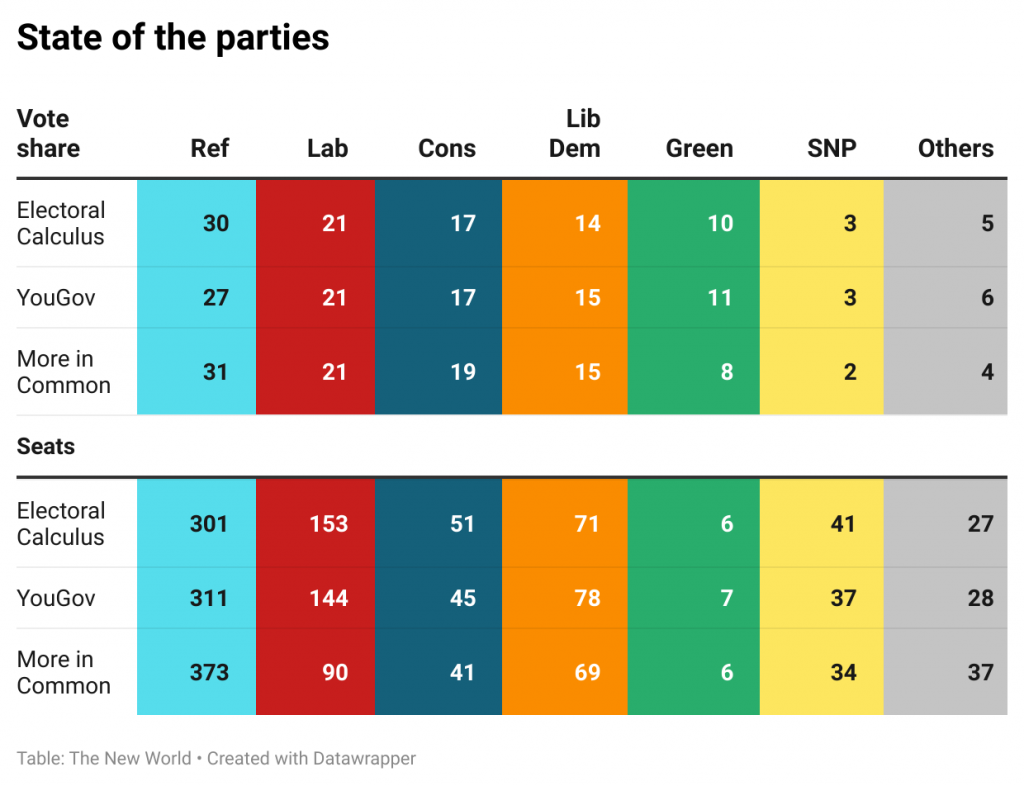

Three recent surveys tell broadly similar stories. With around 30 per cent of the vote across mainland Britain, Reform would be by far the largest party. More in Common gives Farage a clear majority, YouGov and Electoral Calculus show him a little short of the 326 seats needed for outright victory.

Last year the same three companies’ final predictions all overstated Labour’s performance, by between 19 and 42 seats – but they also overstated Labour’s vote share. That was the main source of error. Their current figures should be taken seriously.

What now? One of the most important lessons from recent polls is that many more seats next time will be won and lost by small margins. YouGov finds that 82 Reform MPs would have majorities of less than 5%. A small rise in its national support would give it a large majority – while a small dip could prevent it being the largest party.

More widely, YouGov’s figures indicate an average majority across all constituencies of just 10 percentage points, well down from the 16 points in last year’s election and 26 points in 2019. It follows that small errors in overall voting intention, or shifts in public sentiment, would cause more seats to change hands than similar shifts in pre-Reform days.

Suggested Reading

Why is the mainstream media so uninterested in the Nathan Gill scandal?

In short, the recent surveys point to a huge amount of uncertainty about the next election – especially if Reform’s bubble bursts. Today’s polls suggest the joint support of the two main legacy parties, Labour and Conservative, is now below 40%, less than half the 84% just eight years ago. We are in uncharted territory. But for what it’s worth, history tells us that opposition parties benefitting from government unpopularity have always slipped back significantly from their mid-term peak, typically by around ten percentage points.

The pattern is familiar. Mid-term polls and by-elections allow voters to express their discontent with the government of the day (”send a message” is the cliché). But, to update Ecclesiastes, there is a time to moan and a time to choose. General elections are a time to choose.

It’s possible that Reform will peak well above its current level. Even so, it’s clear that it has been gaining ground because of the public perception that the government has failed, especially on immigration and the economy, while the Tories have yet to be forgiven for the state Britain was in when they were voted out of office.

This is unquestionably a time of moan and protest. Farage is shrewd enough to know this. Hence his attempt to convert protest votes into positive support, almost weekly presentation of new policies that he says a Reform government would implement.

However, unless he succeeds in persuading voters that he really could run the country, he risks watching his electoral soufflé collapse. The same vote-to-seat gearing that puts Farage in Downing Street with 30% will punish him if he gets much less. With 25% support, Reform may not be the largest party. With 20%, it might not even be the official opposition.

There is one factor that could upset these calculations – in either direction. Last year, tactical voting cost the Conservatives dear, with the Liberal Democrats in particular benefitting. We cannot know how much tactical voting there will be next time, or what its overall impact will be. YouGov’s current data shows Labour losing 231 seats to Reform. But in all bar 19 of them, the combined votes of Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Greens are greater than Reform’s support. It’s fanciful to imagine every single progressive voter lining up anywhere behind a single candidate; but determined anti-Reform tactical voting could keep Farage out of Downing Street.

Likewise, Labour would lose 76 of its current expected 144 seats if all Tory and Reform supporters voted the same way locally.

Some weeks ago, I argued on Substack that Britain’s voters still divide broadly between left and right in their values. Who governs Britain after the next election could turn on which cluster of tribes, left or right, succeeds more in uniting, seat by seat, to defeat those on the other side of the line.

Meanwhile, if forced to bet on it, I would put my money on Reform slipping back between now and the next election. But if immigration dominates campaigning in 2029, and Labour is still blamed for economic failure, Farage could overcome the hostility of up to two-thirds of voters and still end up as prime minister.