Suddenly the talk at Westminster is of the government wanting a closer relationship with the European Union. What should we make of this? Let us start with the basic fact that the pro-Brexit majority in 2016 has gone. It has literally died out.

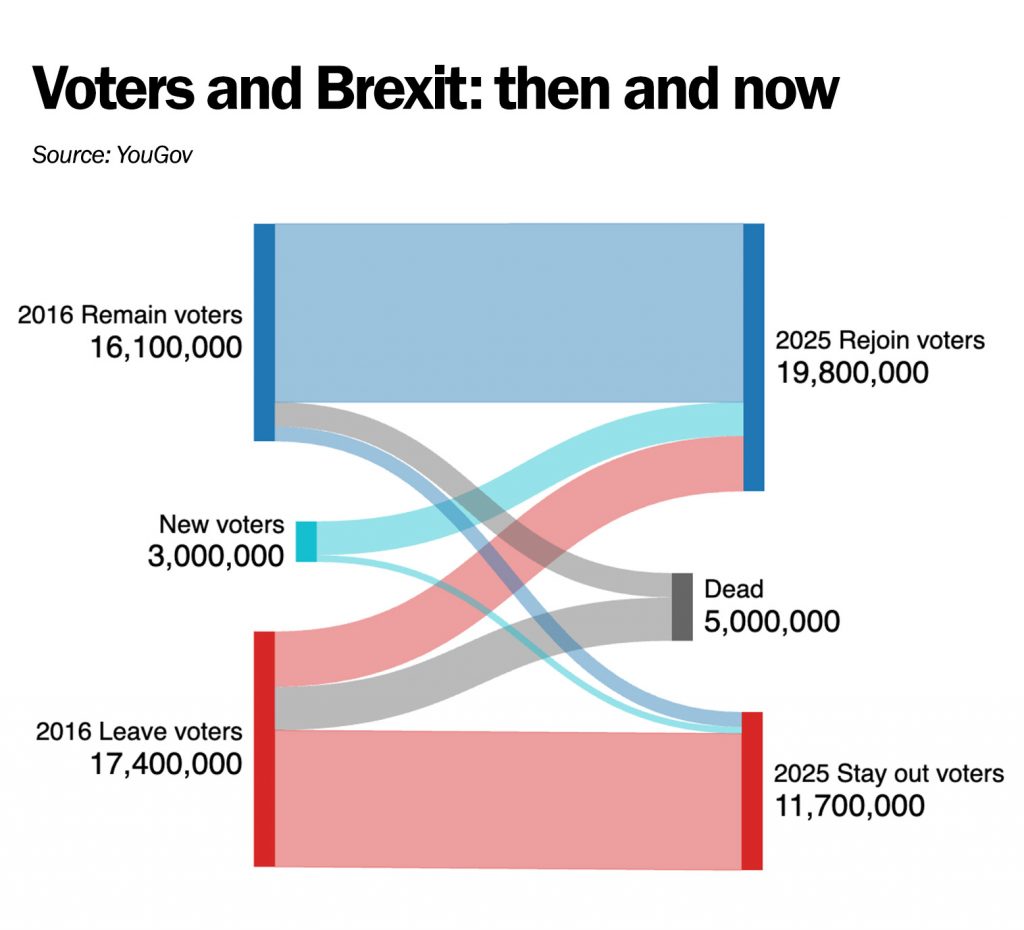

Nine years ago, 17.4 million people voted to leave the EU, 16.1 million to remain – a majority of 1.3 million.

Since then, more than six million Britons have died. We know a) that turnout among older voters was higher than average, and b) that those over 65 backed Brexit by 64-36%. That gives the best guide to the votes of those who have died – with the highest death rates among the oldest, most pro-Brexit, voters balanced by the deaths of younger, less pro-Brexit voters.

Assuming that five million of the six million people who have died turned out in the referendum, 3.2 million people who voted Leave have died, as against 1.8 million who voted Remain.

This means that among people who are alive today and who voted in the 2016 referendum, remainers exceed leavers by 14.3-14.2 million.

Yes, that’s an estimate, based on cautious assumptions. We can’t be certain that the remainers are now ahead. Statistically, it’s best to consider the survivors’ historic verdict as a dead heat. Given all that has happened in recent years, that is significant in itself. However, there are two more facts that tilt the balance further towards the pro-EU camp.

First, six million people have reached voting age since the referendum. YouGov’s data suggest that they back rejoining the EU by five-to-one. However, younger Britons turn out less than their parents and grandparents. If we assume that just three million of them would actually vote, then remainers outnumber leavers by 2.5 to 0.5 million.

All of which means we are looking at remainers outnumbering leavers by 16.8-14.7 million – a majority of two million. We are told that it would be undemocratic to overturn the 2016 referendum result. After almost ten years, that requires a belief that the votes of the dead count for more than the views of the young.

Secondly, those figures assume that nobody has changed their mind since the referendum. But some have. Again according to YouGov, 8% of those who voted Remain would now vote to stay out, while 29% of Leave voters want to rejoin. That’s 1.1 and 4.1 million respectively. (Until 2021, when Brexit was fully implemented, few Leave voters said Brexit was a mistake. The proportion has risen steadily as the costs of Brexit have become clear.

As the table shows, the combined impact of demographics and changed minds is to convert a 1.3 million majority for leaving the EU into an 8.1 million majority for rejoining it. Even the greatest landslide election victories have come nowhere close to this lead in the popular vote.

To repeat, these are estimates. The true figures may well be slightly different. But the two factors – demographic and attitudinal – have unquestionably moved public opinion in a pro-European direction. My estimated majority for rejoining the EU is too large to be overturned by sampling error, or even turned into a nail-biting outcome.

The far greater uncertainty is how voters would react if the government now sought much closer trading links with the EU – either rejoining the customs union and single market, or something similar but with a different name. I agree with Anthony Wells, my former YouGov colleague, who told The Times: “The question is whether, when it came to it, voters would really want to open the can of worms that such a change in approach would involve.”

There would plainly be a big public debate. What could ministers do to win it? The key group are the four million Leave voters who have switched sides. If they return to their pro-Brexit stance, the pro-European cause would be lost. At the very best, the electorate would be evenly divided. Ministers would be denied the level of public support they really need for a pro-European strategy to stick.

According to a YouGov survey for Best for Britain, the dominant reason why so many Leave voters have changed sides is that only 25% of them think Brexit has been a success, while 35% judge it a failure. Among the 35%, the two most commonly cited reasons are that it has damaged Britain’s economy and failed to generate the promised extra money for the NHS.

Keir Starmer and, more strongly, David Lammy have started saying more clearly that Brexit has been bad for the economy. They could scarcely say otherwise. Until recently, the consensus view among economists was that Britain’s gross domestic product has taken a 4-5% hit from Brexit. Last month, America’s highly respected National Bureau of Economic Research calculated that the cost is actually much greater. Its team included Philip Bunn, an economist at the Bank of England. This is their verdict:

“By 2021, five years after the referendum, our estimated GDP impacts were very close to these initial predictions at between 4% and 6%. However, the effects have since continued to grow over a longer horizon. One reason the magnitude of these initial estimates may have been too low is because they were made without including the additional costs of uncertainty… We estimate that by the start of 2025, the UK economy was approximately 8% smaller than it would have been without Brexit.”

Eight per cent amounts to £240bn a year. This would have given the government an extra £80-100bn in tax revenues to spend on hospitals, schools, strengthening our armed forces, fighting crime and reducing poverty. Leave voters are right to complain that Brexit produced no NHS dividend. Our Brexit-weakened economy stood in the way.

Earlier this year Starmer negotiated a reset with the EU that, we were told, would “support British businesses, back British jobs, and put more money in people’s pockets.” It offered real benefits, such as making it easier to trade food and drink. But how big were those benefits?

I checked back with exporters I had first spoken to at the start of this year. Each had told me a story of niggles, frustrations, delays and extra costs. After Starmer’s deal, they judged that his reset would do no harm, but help only slightly. Their verdict chimed with the calculations made by the Centre for European Reform. They predicted a long-run benefit of 0.3-0.7% of GDP. The reset would repair less than one-tenth of the damage done by Brexit. The reset was no game-changer. At most it was a game-tweaker.

Back to the political challenge facing the government. To win the argument with those critical, disappointed Leave voters, it needs a credible plan, now more than ever, to repair all the damage, not just one that fiddles around at the edges. This means a far more radical policy than that of the reset – and an end to cherry-picking diplomacy with Brussels. It requires a return to frictionless trade, with no ifs or buts. Lammy may have gone beyond strict government policy last week when he enthused about the Customs Union; but if his loyalty was a bit wobbly, his logic was rock solid.

To win the argument, ministers will need to confront the charge that Britain must accept EU trading rules and the decisions of the EU’s Court of Justice. Their task is to show that the benefits to jobs, living standards and cash for public services outweigh the costs of curbing British sovereignty. Any attempt to duck the issue and pretend that we can both emerge from the Brexit tunnel and keep our own rules is bound to fail.

In short, ministers need courage, clarity and confidence. You don’t see any signs of that so far? Perhaps they are just saving them up.

Peter Kellner is founder of YouGov. His substack can be found here