PICK OF THE WEEK

“Wuthering Heights” (general release)

In her great 1964 essay on the subject, Susan Sontag wrote that “Camp sees everything in quotation marks.” It is a shame that she is not around to render aesthetic judgment on Emerald Fennell’s third movie because I am pretty sure she would say: “Wow. Now that is camp.”

The quotation marks around the movie’s title are a big clue. My favourite adaptation of Emily Brontë’s novel – first published in 1847 under the pseudonym Ellis Bell – is still Andrea Arnold’s rough-hewn, elemental film of 2011 (also the first in which Black actors played Heathcliff, who is described in the book as “a dark-skinned gipsy”).

But Fennell’s take on the story is not really an adaptation: more like a version of a version of a version; inspired, as she has said, by her memories of the novel when she fell in love with it aged 14. She does not so much take liberties with the text as unleash fabulous anarchy upon it.

In the leading roles, for a start, she has unashamedly cast two ridiculously good-looking screen stars – Margot Robbie as Catherine Earnshaw and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff – with an eye to making a film that will be “this generation’s Titanic” rather than to appease campus literary critics. The character of Cathy’s brother Hindley is dispensed with entirely and Isabella (Alison Oliver) becomes the ward of Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif) rather than his sister. Mr Earnshaw (Martin Clunes, splendid) is much more prominent than in Brontë’s original.

Thrushcross Grange, the Lintons’ home – which becomes Cathy’s too when she marries Edgar – is less a Yorkshire manor house than a hyper-real palace of vast spaces, primary colours and kitsch modernity. Costume designer Jacqueline Durran ditches historical accuracy in favour of fever-dream impact, mixing vintage Thierry Mugler and Alexander McQueen with Chanel jewellery, Russian hats and cellophane.

When Heathcliff, dismayed by Cathy’s marriage, deserts Wuthering Heights and then returns years later, wealthy and well-groomed, he looks more like a Britpop Byron than a Georgian entrepreneur. And the love of his life, the childhood friend with whom he ran across the crags and fields, is now a fairy tale princess, apparently dressed by Balenciaga.

Add in the soundtrack by Charli xcx, and you have a movie that owes much more to acid culture, rock videos that go heavy on the dry ice, Wes Anderson formalism, and behind-the-scenes fashion sizzle reels than to the traditions of the well-behaved literary adaptation. This is truly an exercise in world-building rather than narrowly bookish homage.

Fans of Fennell’s Saltburn (2023) will not be surprised by the movie’s steaminess – far more explicit than the suggested passion in the book, though true to its Freudian juxtaposition of Eros and Thanatos. The film could also not make the moorland more fetishistic if it tried: this really is Fifty Shades of Grouse.

As I say, Arnold’s adaptation is still top of my list. But I truly enjoyed Fennell’s dialled-up vision and its counter-cultural determination to thumb its nose at contemporary primness and tone policing. “Nobody likes a sourpuss,” says Mr Earnshaw. “Now where’s my fucking horse?” Exactly.

Crime 101 (general release)

“What do you see? What do you feel? Remember that there’s great power within you.” The meditation app favoured by Los Angeles insurance broker Sharon Colvin (Halle Berry) provides an intermittent Zen commentary to Bart Layton’s terrific heist thriller; its soothing affirmations sharply at odds with the status anxiety, pulsing greed and compressed resentments of its characters.

Inspired by Don Winslow’s hardboiled 2020 novella – which was dedicated to Elmore Leonard – Crime 101 takes its title from the course designation given to US college starter classes. But there’s a double meaning in the allusion to Highway 101, the north-south route on the Pacific coast along which jewel thief Mike (Chris Hemsworth) has carried out a series of meticulous robberies.

Alone in his department, LAPD detective Lou Lubesnick (Mark Ruffalo, now well-established in his paunchy cop phase after last year’s excellent Task) spots this geographic pattern, matched by the consistent non-violence of the thefts.

“People who grow up in chaos crave order,” Sharon tells Mike when he seeks to involve her in a huge criminal payday. The tension between smooth surfaces and internal bedlam – in LA itself and its citizens – is at the heart of the movie.

And never more so than when Mike’s seen-it-all mentor and fence Money (Nick Nolte) loses confidence in him and recruits the trigger-happy biker Ormon (Barry Keoghan) to take over his scores. Not since the arrival of drug dealer Marlo Stanfield (Jamie Hector) in season three of The Wire has there been a more captivating, reckless pretender to criminal dominion.

Blonde-thatched, twitchy and ultra-violent, Keoghan’s character is a daemon consumed by ambition and fury; a chaos agent who sneers at Mike’s caution and his dream of a life free from crime.

Crime 101 is an explicit love letter to the movies of Michael Mann, including Thief (1981), Collateral (2004) and – especially – Heat (1995): Mike’s tentative romance with Maya (Monica Barbaro) is a nod to the fateful relationship between ice-cool thief Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) and graphic designer Eady (Amy Brenneman).

But Layton’s homage is not confined to one director: the influence of William Friedkin is also clear in the spectacular car chases (best enjoyed in 4DX). In a wonderful scene towards the end of the film – in which both men are pretending to be someone else – Lou and Mike discuss the relative merits of Steve McQueen’s most iconic roles.

The cast is superb: Jennifer Jason Leigh appears in only two scenes as Lou’s soon-to-be-ex-wife Angie and is still memorable. Corey Hawkins is great as Lou’s exasperated partner, Detective Tillman. So is Tate Donovan as Monroe, one of Sharon’s plutocratic clients whom Mike selects as his final mark.

“You hold the power to create all that you desire out of nothing,” says the app. That’s the delusion with which all the characters struggle in Crime 101, and the incantation that the City of Angels itself whispers to them, and to us.

THEATRE

Dracula (Noël Coward Theatre, London, until May 30)

From the moment that Cynthia Erivo walks onstage, lies down and begins to speak as Jonathan Harker – the young lawyer despatched to Transylvania to arrange a property deal with Count Dracula – she commands the attention of the audience with extraordinary power and agility.

Thirteen years after her acclaimed performance as Celie in The Color Purple at the Menier Chocolate Factory, which transferred to Broadway, one is reminded of her greatness as a stage performer. In this adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 horror classic – following his triumph with Sarah Snook in The Portrait of Dorian Gray in 2024 – Kip Williams once again entrusts the whole story to a lone actor. Once again, the theatrical experience is riveting.

In taking on 23 roles, and narrating a 20,000-word script, Erivo is more than a quick-change artist. Yes, as the doomed Lucy Westenra she wears a white dress and long blonde wig; as Professor Abraham Van Helsing she has the beard of a sage and the golden crucifix of a vampire hunter; as Dr Jack Seward, administrator of the asylum near the count’s new estate, Carfax, she adopts the guise of a fretful Victorian gentleman; as Quincey P Morris, Lucy’s Stetson-wearing suitor, she plays up the character’s Texan swagger and wit; and – best of all – as Dracula himself, with red hair, natty white suit, fangs and talons, she portrays a creature of diabolical charisma, supernatural power and (unexpectedly) pathos.

Yet none of this would be work – or work so well – were it not for the connective tissue of Erivo’s storytelling voice. As ever, Williams uses screens, Steadicams, music and imaginative set design to great effect: achieving a hypermodern form of drama in which the solo actor is constantly interacting with versions of herself and high-tech visual effects, in what amounts to cybernetic theatre.

“I am not a creature of the underworld,” says the count. “I am a thing of the mind.” That the line rings so true is a tribute to the success of this audacious and absorbing production.

BOOK

The Score: How to Stop Playing Someone Else’s Game, by C Thi Nguyen (Allen Lane)

From time to time, a book comes along that causes the reader to reconsider just about everything. In The Score, C Thi Nguyen, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Utah, deploys his scholarly research on games, values and rankings as a prism to reinterpret our hypermodern world. The results are extraordinary.

Central to his thesis is what he calls “value capture” which “occurs when you get your values from some external source and let them rule you without adapting them.” Metrics, he readily acknowledges, have many constructive uses; but they can also become tyrannical, deadening and a poor guide to what matters in life.

So desperate are we to chase social media clicks and likes, or better academic grades, or higher rankings for the services we offer, that we lose sight of nuance, subtlety and joy. “If we let institutional metrics set our values and drive our lives,” Nguyen writes, “we end up chasing what’s easy to count, and not what’s really important.”

This leads, ultimately, to value collapse: “a feedback loop whereby over-simplifying your values changes how you approach the world, what you notice about it, and what you spend time exploring.” We are hypnotised by a process of “objectivity laundering” that makes us the serfs of metrics we imagine to be value-neutral – but are no such thing.

So what to do? Ingeniously, Nguyen detects in games (broadly understood) a healthy, flexible form of score keeping and an enriching form of endeavour that he calls “striving play”. Every game has an objective, of course, but “we adopt a goal in order to have the struggle that we really want.”

Whether playing pickup basketball, charades or Red Dead Redemption 2, we strategically pursue an objective in order to engage in a challenge that we find intrinsically enjoyable. “Games offer value clarity,” he writes. “They are an existential balm for the confusion of ordinary life.”

Part intellectual thesis, part memoir, part carnival of personal enthusiasms (it begins with the author’s joyous discovery of rock climbing), The Score is beautifully written and full of aphoristic wit. Games are “metrics methadone”; “a kind of spiritual vaccine, an inoculation against the harsher institutional scoring systems that they resemble”; and (best of all) “toy governments, but for fun.”

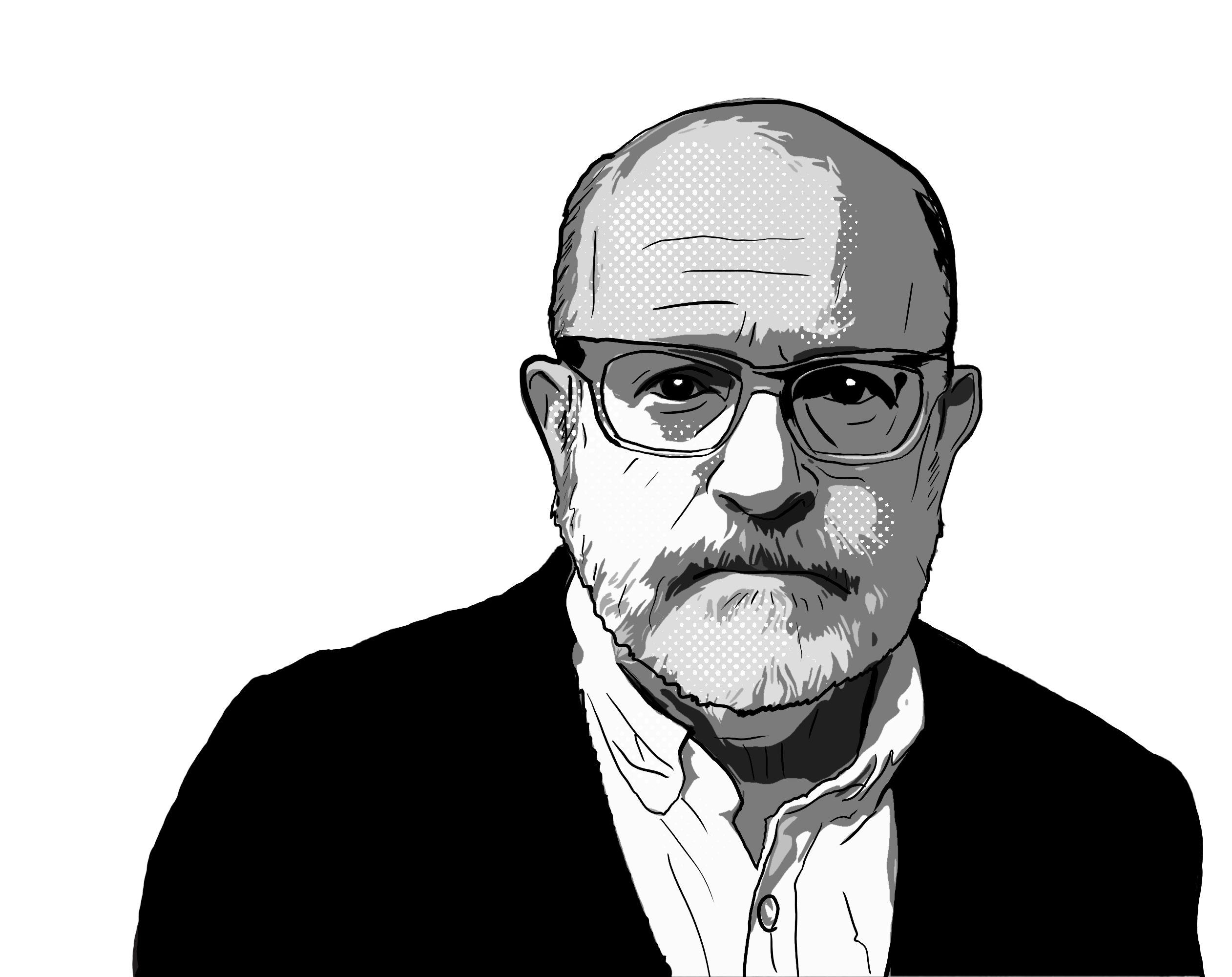

This rigorous comparison of institutional metrics and games supports his central message that “[t]he meaning of life is not in the outcome but the process.” At their best, games “offer the possibility of a splintered, decentralized, hyper-tailored form of life.”C Thi Nguyen will be talking to TNW founder and editor-in-chief Matt Kelly and me in a forthcoming episode of The Two Matts.