PICK OF THE WEEK

Othello (Theatre Royal Haymarket, London, until January 17)

The great Shakespearean scholar AC Bradley hailed Othello as “a being essentially large and grand, towering above his fellows, holding a volume of force which in repose ensures pre-eminence without an effort, and in commotion reminds us rather of the fury of the elements than of the tumult of common human passion.”

He might have been describing David Harewood who, in Tom Morris’s tremendous production, returns to the role that he first played at the National Theatre in 1997 (shamefully, no Black actor had ever been cast in the role at the NT before then). His Othello is a figure of colossal dignity, a Venetian general of mythic accomplishments – which makes the spectacle of his psychological disintegration all the more compelling.

In this respect, it is important that Caitlin FitzGerald’s Desdemona is not the passive ingénue of some interpretations, but a woman deeply in love with her new husband who is nonetheless uninhibited in her exasperation as their marriage is mortally threatened by intrigue and lies (“O, these men, these men!”).

At the heart of it all is Toby Jones’s astonishing performance, the best Iago I have ever seen. Cleverly repurposing his status as the face of national decency – sealed by Mr Bates vs The Post Office (2024) – he presents the scheming ensign as a crumpled figure in Dad’s Army fatigues, excluded from the glamour of high society, taken for granted (as he sees it) by Othello. His deceit could scarcely be more deadly, or more absolute: “I am not what I am”.

The origin of Iago’s hatred for the Moor is one of the great controversies of Shakespearean drama. Coleridge wrote of his “motiveless malignity”. True, he has been denied the office of lieutenant by Othello, who favours Cassio (Luke Treadaway) instead, and suspects that his own wife Emilia (Vinette Robinson, excellent) has been unfaithful to him. But, as played by Jones, he is driven by deeper forces: a love of power, of manipulation, of choreographed disaster. More than simply a man slighted, he is an arsonist of the psyche.

All of which flows from a wretchedly amoral view of humanity – “men are men” – and a genius for undermining the self-esteem of others. “Reputation, reputation, reputation!” cries Cassio. “O, I have lost/ my reputation! I have lost the immortal part of/ myself, and what remains is bestial. My reputation,/ Iago, my reputation!” In the age of clicks and likes, this man-made despair feels all too contemporary.

The tragedy of Othello is, in its way, as multi-layered as Lear’s. He knows that his suspicion of Desdemona will destroy him – “when I love thee not,/ Chaos is come again” – but cannot fight off the fears that his treacherous friend has implanted within him. For all his martial achievements, he is a man of profound vulnerabilities – fault-lines traced brilliantly by Harewood. Enhanced by PJ Harvey’s score and Ti Green’s design, the whole production is a tour de force.

Suggested Reading

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere is music to your ears

FILM

Bugonia (selected cinemas)

In her fourth feature film made in collaboration with director Yorgos Lanthimos, Emma Stone plays Michelle Fuller, the chief executive of pharmaceutical company Auxolith; a corporate ninja, featured on the cover of Time and Forbes, officially in favour of family-friendly working hours but clearly contemptuous of them.

Teddy (Jesse Plemons), a beekeeper and deranged conspiracy theorist, plots with his autistic cousin Donny (Aidan Delbis) to kidnap Michelle. He works for her company in the shipping department and believes that his mother Sandy (Alicia Silverstone), who took part in one of its drug trials, is in a coma because of Auxolith’s negligence. But his extremely online investigations have also persuaded him that – wait for it – Michelle is an extraterrestrial from Andromeda and that he can force her to take him to the aliens’ mothership during the next lunar eclipse.

Lanthimos loves the collisions of absurdity and power – witness his breakthrough movie Dogtooth (2009), The Lobster (2015) or Kinds of Kindness (2024) – and Teddy, establishing the “headquarters of the human resistance” in his basement, seeking by a crackpot regime of medication and exercise to rid himself and Donny of their “psychic compulsions”, is a sweatily preposterous figure.

Yet, in the age of “conspirituality”, QAnon and podcasts devoted to secret cabals, UFOs, and the Illuminati, is he really such a fringe figure, or (in fact) a cliché of the new mainstream? When Michelle wakes up, her head shaved (long hair is apparently how the Andromedans communicate with her), she sees immediately what and who Teddy is. “Lies, truth, what’s the difference?” she says to her captor. “I can’t change your mind.”

As you would expect from two world-class actors, Plemons and Stone are electrifying in these exchanges. “99.9 per cent of what’s called activism,” Teddy concedes to Michelle, “is really personal exhibitionism and brand maintenance in disguise.” But he still needs a map of meaning, however ridiculous, to explain what he sees all around him. “We are not steering the ship, Don,” he says to his cousin. “They are.” This is both terrifying and consoling.

Loosely inspired by Jang Joon-hwan’s Save the Green Planet! (2003), Lanthimos’ 11th feature is as bold as ever, drawing upon the director’s unique aesthetic, emotional and moral palette. ‘Bugonia’, by the way, refers to the ancient ritual sacrifice of a cow so that bees might spontaneously emerge from its carcass. This may make more sense once you’ve seen the movie.

STREAMING

Down Cemetery Road (Apple TV+)

After five terrific seasons of Slow Horses, here comes the much-anticipated adaptation by Morwenna Banks of the first novel in Mick Herron’s earlier Zoë Boehm series. Once again, source material, casting and excellent scriptwriting converge to highly entertaining effect across eight episodes.

Sarah Tucker (Ruth Wilson, superb as ever) is an art conservationist in Oxford, married to investment banker Mark (Tom Riley). In the middle of a socially awkward dinner party they are hosting, the house is rocked by a nearby explosion. The impulsively inquisitive Sarah offers to take a get-well card drawn by a neighbour’s child to five-year-old Dinah Singleton (Ivy Quoi), who is recovering in hospital. When she is ejected from the lobby by its staff, she cannot help but dig deeper.

All of which brings her into contact with Zoë (a spiky-haired Emma Thompson, laconic and magnificent), who runs a private investigations service with her husband Joe (Adam Godley). The official explanation for the blast – a gas leak – would make sense, were it not that, as Zoë soon discovers, the gas at the house had been cut off.

Herron’s genius lies in the juxtaposition of ordinary eccentricity with institutional malfeasance; which in this case is provided by the wonderfully sarcastic chief defence spook C (Darren Boyd) and his hapless case officer Hamza Malik (Adeel Akhtar). They are trying to put the genie of a scandal back in the bottle – and, to C’s fury, failing miserably.

I shall not spoil the nature of that scandal but the circuitous path by which Zoë and Sarah – often apart, sometimes, like an irritable Thelma and Louise, together – get to the truth is a satisfying blend of dark thriller and screwball comedy. “Are you deliberately mean, or is there something wrong with you?” Sarah asks Zoë, who wears her leather jacket like armour.

There are great needle-drops – Björk’s Bachelorette, The Clash’s Know Your Rights, Tricky’s Black Steel – and uniformly strong supporting performances, not least Fehinti Balogun as the unflappable assassin Amos. Best of all, there are three more novels to adapt.

BOOK

The Uncool, by Cameron Crowe (4th Estate)

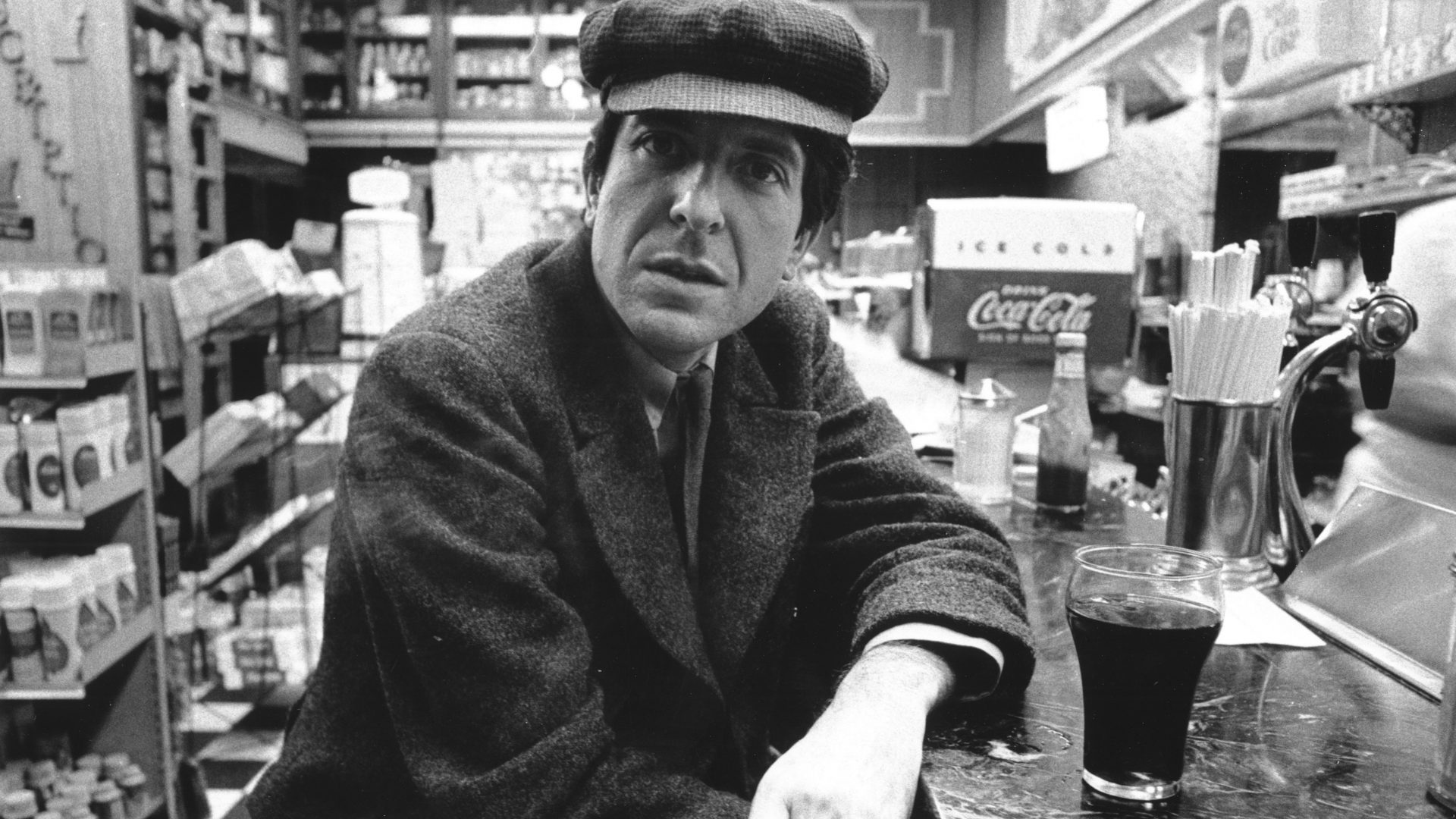

Aged only 15, Cameron Crowe was Rolling Stone’s youngest-ever contributor: a prodigy in the world of seventies rock journalism who wrote memorable articles on the Allman Brothers Band, Led Zeppelin, the Eagles, Joni Mitchell, Fleetwood Mac and many other artists.

That period in his life was dramatised in the fourth film he directed, Almost Famous (2000) and is now recounted in greater depth in this absorbing memoir. When his mother Alice took him to see Bob Dylan in April 1964, something was awoken in Crowe – as in millions of other teenagers. “Music was already more than music,” he writes. “It was a door that opened for three minutes. Sometimes way longer. In the forbidden world there was no judgment. Only your own thoughts and secret desires, slashing through the atmosphere. And when the song was over, the door clanged shut again.”

His first interview – unplanned – was with labour leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez. Taken by his sister Cindy to the headquarters of the underground San Diego newspaper, the Door, he started to write music reviews and discover the sense of belonging that had hitherto eluded him.

Somehow, he befriended his journalistic idol, Lester Bangs, who (as in the movie) urged him to be “honest and unmerciful.” Somehow, he interviewed Kris Kristofferson. Somehow, he was an extra in Orson Welles’s unfinished The Other Side of the Wind. Somehow, he ended up living in a place off Mulholland with Don Henley and Glenn Frey of the Eagles (“a guided missile of creativity”).

Most extraordinary of all, perhaps, Crowe was invited into David Bowie’s world in the mid-1970s for a rolling series of conversations in many locations. “The only problem with this house,” said Bowie on one occasion, “is that Satan lives in that swimming pool… I’ve seen him!”

Like Almost Famous, Crowe’s memoir is as much a homage to family – especially to his late mother – as it is a love letter to music. What he calls the “happy/sad” of great pop maps onto his experience as the youngest of three children and of home; a place of safety marred by a particular tragedy. The Uncool is funny, candid and hard to put down, written by a self-proclaimed “historian of the heart.”