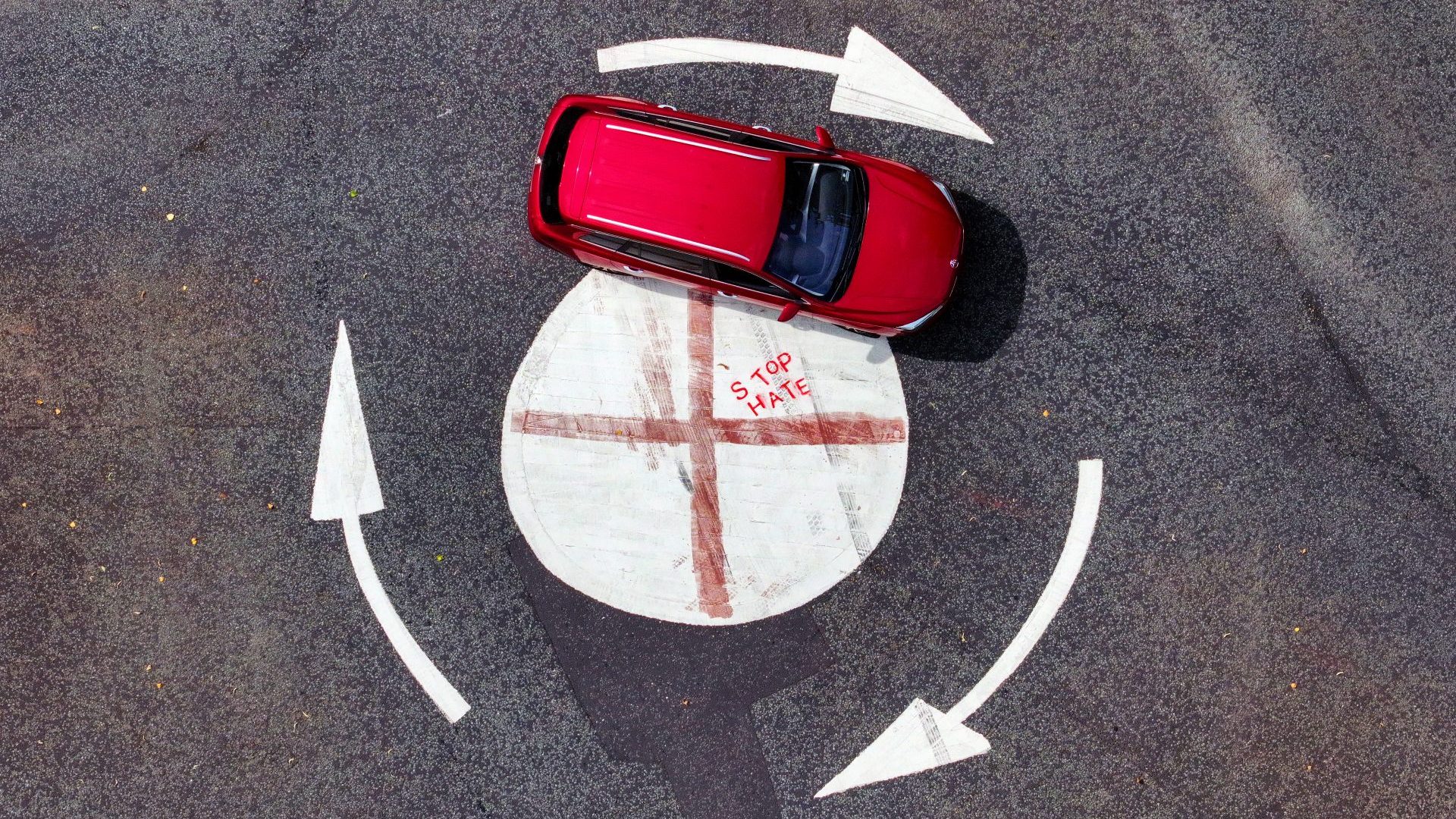

On Saturday, September 13, Tommy Robinson will lead what he hopes will be a mass rally in central London, styled as the “Unite the Kingdom Free Speech Festival”. The longtime scourge of Islam and former leader of the English Defence League predicts that 500,000 to one million peaceful protesters will join him.

“The entire world is going to be watching us,” he says in the pinned post at the top of his X account. “We’re about to inspire the entire western world about what resistance is about.”

The clip is striking because of the tone struck by the 42-year-old Robinson – real name Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, or “Yax” to his closest friends. This is not the pep talk of a Luton Town FC gang leader to his firm before a punch-up with Millwall supporters. Robinson sounds more like a benign headteacher warning his pupils not to disgrace themselves in public on a day trip.

So, no face masks, no alcohol, no aggro: “You’re letting your family down, you’re letting your country down, if you misbehave, if you bring any aggression on the streets of London that day.” He speaks warmly of the Met and his coordination of the event with its officers.

In The Peter McCormack Show on August 28, Robinson also promised that there would be a Black gospel band, Canadian and Australian musicians, and even 110 Māoris performing the Haka ceremonial dance.

Short of singing We Are the World, Robinson is doing all he can to frame the event as a celebration rather than a provocation.

He knows that a big counter-protest – the “March Against Fascism” – has been organised by the campaigning group Stand Up to Racism, which is coordinating coach transport from all over the country. So, in the casino of public opinion, he is engaged in a high-risk wager: that his supporters will behave themselves and not give his perceived enemies in the government and mainstream media the spectacle of violence he believes they are yearning for: “Do you want to hand it to them on a plate?”

Let us not get dewy-eyed about Robinson’s supposed redemption arc. On August 4, he was arrested on suspicion of assault occasioning grievous bodily harm after allegedly punching a man to the ground at St Pancras station. Last Wednesday, the police and prosecutors said he would not face charges. At 5.15pm on the same day, he posted on X: “Now I can say it, fuck around & find out.”

In a lengthy interview with Konstantin Kisin and Francis Foster on their Triggernometry podcast, posted on August 10, he admitted that “I don’t mind a punch-up”. And he didn’t push back too hard when Kisin compared him to the violent character Begbie in Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting. Leopards do not change their spots; and Old Lutonians don’t forget how to knock the other geezer spark out.

That said, it is a huge mistake to dismiss or underestimate Robinson. The line-up of speakers at his rally currently includes Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s former chief strategist, now one of MAGA’s most influential podcasters; and Jordan Peterson, the bestselling in-house philosopher of the new right.

Like him, these two men have recognised – and made lucrative careers out of – the buckling of the social contract, and the international populist rebellion against the old elites, the “deep state”, globalisation and mass immigration. Hate them all you like: they have energy, momentum and (most important) stamina.

In the 10 years since the EDL folded, Robinson has devoted most of his time to new media, describing himself (risibly) as a “journalist”. Under the wing of Ezra Levant, the Canadian lawyer and owner of the hard right Rebel News platform, he has produced thousands of videos, as well as books and merch.

In her recently published memoir Hate Club, Robinson’s former colleague Lucy Brown describes the often tawdry, hyperkinetic milieu in which his small production team raced around the country filming clips to post online, troll their opponents and command digital attention.

Though often mocked for his height – he is 5’7” – he was the undisputed “Godfather” of the gang. “We lined up the shot, gave him the ball, and time and again, it bounced back and hit him in his own stupid face,” she writes.

Even so – as Brown’s account attests – he keeps getting off the canvas. In and out of prison and rehab, bankrupted, treated as a pariah, Robinson has never lost his sense of purpose. And therein, I think, lies a deeper and extremely important lesson about the multi-layered movement of which he has been and remains a leading figure.

Suggested Reading

Britain’s real immigration scandal is not the one you think

What he grasps, instinctively or otherwise, is precisely the role that he is meant to play. When he ran for the European Parliament in 2019, as an independent candidate in North West England, he was utterly humiliated, gaining only 2.2% of the vote and losing his deposit. This was a serious error, not to be repeated.

Social movements thrive and are consequential when each part of the whole understands its allotted function and sticks rigorously to it. Nigel Farage leads the electoral campaign for office, is the principal voice in the mainstream media and (when invited, as this week) appears before US congressional committees.

Though he leads a parliamentary party of only four, he is now setting the agenda in Westminster and beyond, routinely leaving the prime minister and Kemi Badenoch in the dust (witness his speech last week promising mass deportation and the UK’s withdrawal from a host of international treaties).

According to a BMG poll in Saturday’s i newspaper, Reform is supported by 35% of voters, 15 points ahead of Labour. No less striking was a More in Common survey for the Sunday Times, which indicated that 21% of 16- and 17-year-olds would vote for the new party proposed by Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana – but that 23% would back Reform (only one point behind Labour, supposedly counting on all these newly enfranchised teenagers coming to Keir Starmer’s rescue).

At the other end of the continuum is Homeland, a genuinely neo-Nazi party, which splintered from Patriotic Alternative in April 2023, and has been a shadowy force online, organising demonstrations outside asylum hotels in the past month. In locations such as Peterborough, Nuneaton, Weathersfield and Epping, Homeland activists have used Facebook groups to mobilise and coordinate action.

In the marchlands between online fascists and Farage roves Robinson. Though he now supports Advance UK, Ben Habib’s breakaway party – as does Elon Musk – his core task is to leverage his public profile in “Podcastistan” and to front major rallies that will (he hopes) dramatise the anxieties of ordinary British families rather than the longing for violence of testosterone-charged young men.

This has (for example) involved the surreal spectacle of Jordan Peterson reverently telling him Bible stories in a podcast last year that achieved more than 2.7 million listens. Robinson’s own speaking style is that of the motormouth in a London working men’s club: he doesn’t do soundbites or neatly packaged interviews.

Instead, he tells long, involved stories that are almost impossible to follow but, like Trump’s “weave”, have a persuasive power that has absolutely nothing to do with logic. This barstool patter is useless for Newsnight or Good Morning Britain. But it is perfect for long-form podcasts. As so often in effective social movements, technology is at the heart of the matter (the Protestant Reformation would not have happened without the printing press; John F Kennedy would not have defeated Richard Nixon without television).

Too many progressives draw comfort from the fact that Farage and Robinson loathe each other. It is true that they do. As long ago as 2018, Farage resigned live on his LBC show from the UK Independence Party, citing the advisory role that the then leader Gerard Batten had given to Robinson.

On The Peter McCormack Show last week, Robinson condemned “flip flop fucking Farage” as “a City banker who does not give a flying fuck about the working class”. Confirming that his hatred of Islam is undimmed, he expressed disgust that Farage had given Zia Yusuf – “some random Muslim” – a seat at Reform’s top table.

But this feud is much less important than the operations of the movement as a whole. Though such personal divisions naturally generate headlines, they can distract from deeper synergies. To put it another way: camaraderie is much less important than division of labour.

This is because – broadly speaking – Farage, Robinson and organisations like Homeland have coalesced around a hard core of issues: grooming gangs, asylum hotels, state control, net zero, and the bleak sense so many parents have that their children’s lives will be worse than their own.

Suggested Reading

Rejoin isn’t the issue of the era. Racism is.

To an extent that is still radically under-reported, Covid enabled the new right to broaden its message from immigration to the notion that freedom itself was imperilled, that today’s statecraft was both amateurish and sinister. The movement’s constituent cohorts share the view that Labour’s dismal performance in office is a counterpart to Joe Biden’s presidency: the necessary prelude to an authentically nationalist era.

In Robinson’s words: “It had to happen. We needed Keir Starmer. We needed to see the weaponisation of the judiciary, we needed to see the oppression of the working class. We needed to see the attack on British people who dared to voice their concerns. We needed to see Lucy Connolly imprisoned.”

It doesn’t matter whether each part of the movement likes or even talks to every other part. What matters is that each performs its task and that the broad trajectory remains intact.

This has always been true. In 16th-century Germany, the mainstream Protestant followers of Martin Luther loathed millenarian radicals such as Thomas Müntzer. But they shared an even deeper loathing of the Roman Catholic clergy. Division concealed effectiveness.

In the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks needed the Mensheviks (until they didn’t). In 2016, the official pro-Brexit campaign, Vote Leave, and Farage’s Leave.EU publicly scorned each other. But, as complementary forces, they led the UK out of the European Union.

There is an old Marxist saying that “not all conspiracies are conscious”. Movements are more often organic than coordinated. And this is especially so in an age in which loose-knit networks matter more than traditional institutions; when the old partition between mainstream and fringe is wholly porous.

As the Oxford academic Philip N Howard argues in his important book Pax Technica (2015): “The state, the political party, the civic group, the citizen: these are all old categories from a pre-digital world.” To understand how power works today, Howard writes, we must understand it “as a system of relationships between and among people and devices”.

The fashionable coping mechanism among progressives in 2025 is to claim that the voters will calm down. They will scrutinise and cost Farage’s proposals and find them ludicrously wanting. They will see Robinson on social media and dismiss him as an irredeemable jailbird, rebranded in a smart polo shirt. They will recognise how tough it is for poor Starmer and wait patiently for Labour’s five-year strategy to deliver.

In reality, the electorate is better understood as a heavily concussed trauma patient in a high-dependency unit who has experienced a long and pulverising series of shocks: the financial crash, austerity, Covid, the cost-of-living crisis, unaffordable housing, technological hyper-revolution, and bruising inequalities, whereby wages stagnate but the wealthy keep getting wealthier.

As the monitor bleeps, Labour is standing by the bed with a screen of bar charts and data viz, talking drearily of “fixing the foundations”, “milestones” and (for some reason) “a toolmaker”. But all the desperate patient wants is for the pain to stop, for someone to listen. Why can’t they just pay attention? Just for a moment?

This is the context in which the new right is thriving. It offers only snake oil; scapegoats not answers; dopamine hits not a decent life. But like all the best hucksters, it does so persuasively.

It is persistent, and immune to just about everything that the establishment throws at it; understanding that, in complex societies where social stability is very tightly geared, successful disruptive movements depend not upon absolute numbers of supporters but intensity of emotion. Right now, this particular movement is winning.

Will the fever break? It might. But, then again, there is no intrinsic reason, no law of political science ensuring that it will. “We’re now,” according to Robinson, “bordering on a British revolution. I totally believe we are”. On September 13, that bold claim will be tested as never before.