“If you can learn a simple trick, Scout, you’ll get along a lot better with all kinds of folks,” Atticus Finch tells his daughter in To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

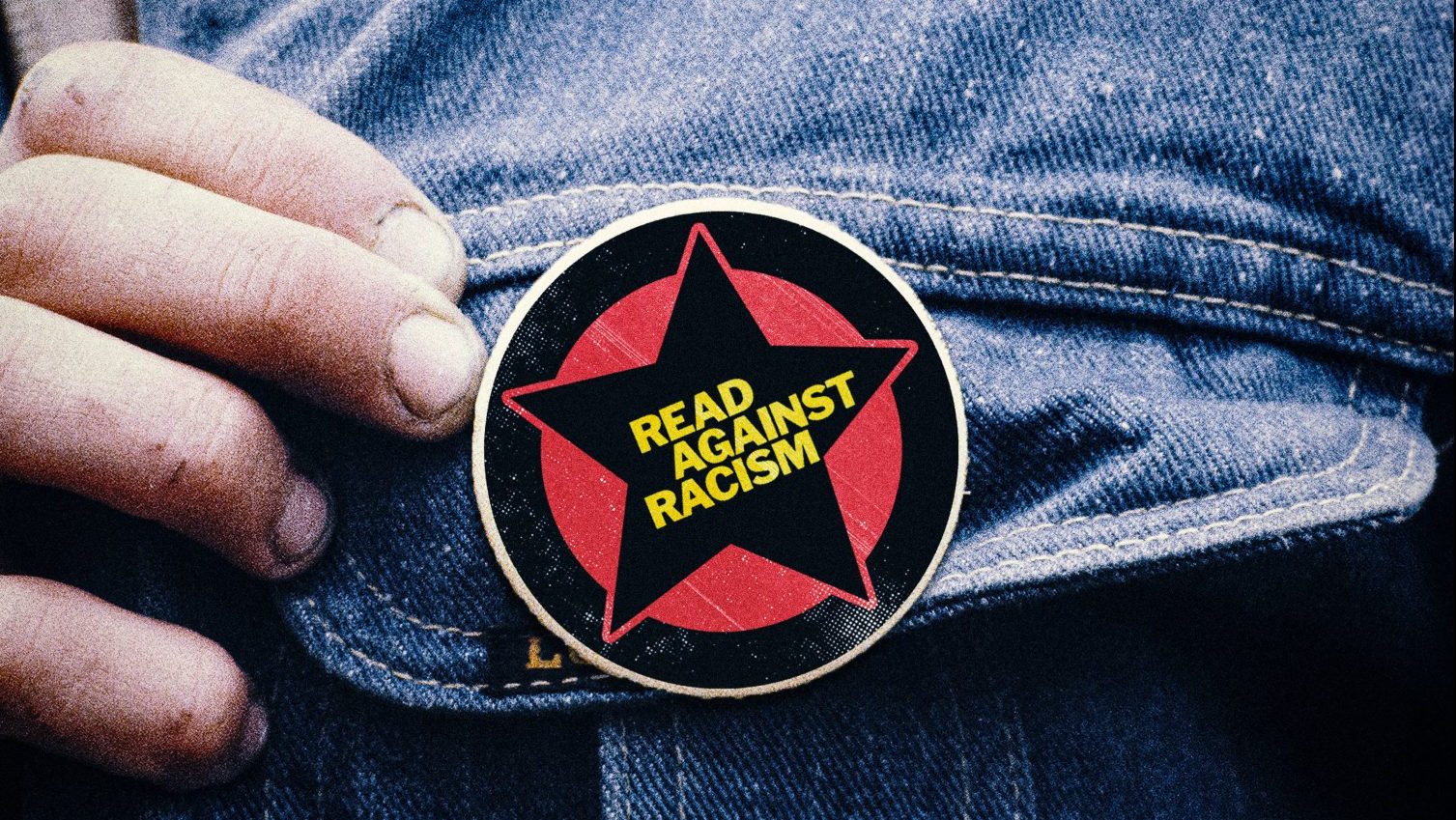

But how is this done? Or (more specifically) what practices encourage the kind of radical empathy that Harper Lee’s lawyer prescribes? Allow me to suggest that reading – reading often, closely and critically – is a significant part of the answer.

As Harold Bloom puts it in How to Read and Why (2000), the company of books “returns you to otherness, whether in yourself or in friends, or in those who may become friends… One of the uses of reading is to prepare ourselves for change.”

Though reading is a solitary habit, it encourages social instincts. It is a solvent of preconception and prejudice. It invites us to confront and consider dramatically different perspectives and experiences. It is one of the foundation stones of modern pluralism and one of the best ways of defeating the racist impulse.

There are obvious senses in which this is true. No serious reader of Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987) can fail to be moved by the horrors of American slavery and its legacy. Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) was, and remains, a thrilling introduction to the energy, drama and fizzing multiplicity of post-colonial culture.

Percival Everett’s James (2024) – a Pulitzer-winning reimagination of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) – narrates Mark Twain’s classic from the point of view of the fugitive slave Jim. The shift of perspective, depth of characterisation and compelling prose yield a work of true literary alchemy.

As Everett himself has observed: “The first thing that fascist regimes do is burn books. Reading is the most subversive thing we can do in a culture.” The poisonous creed of racism is nourished by dull literalism, depleted imagination and a diminished capacity to think as others think. When we read, we are invited to escape the stockade of the fearful self.

In 2025, this is indeed counter-cultural. Walt Whitman’s “I contain multitudes” has long been a cliche. It is also contrary to the spirit of the age. The most dangerous tendency of hypermodernity is to embrace only one tribe, one ideology, one species of righteousness, and, at the deadly extreme, one race.

In matters of culture, it is always hard to distinguish symptom and cause, causation and correlation. But it seems to me – at the very least – suggestive that the rise of the populist, nativist right has coincided with the dramatic decline of reading.

According to a study last year conducted by Censuswide, a third of adults in the UK say that they have given up reading. A survey in the US in 2023 showed that only 16% of Americans read for pleasure, down from 28% in 2003.

Last December, research published by the OECD showed that literacy is “declining or stagnating” in most developed countries. A much-discussed Atlantic article by Rose Horowitch in October 2024 described the exasperation of teachers at top US universities that “many students no longer arrive at college – even at highly selective, elite colleges – prepared to read books… they struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot.”

It is not nostalgic to express alarm at this trend. On the contrary: this is a hypermodern crisis, a serious mismatch between the skills and habits we are nurturing and the world in which we think, feel and act. Precisely when we need the muscles of imagination, empathy and curiosity to be strong they continue to atrophy from disuse.

It is, of course, quite possible to read widely and remain a racist. The great literary thinker and philosopher George Steiner wrestled for his entire life with the terrible paradox that Germany – the nation of Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Schiller, Heinrich Heine and Rainer Maria Rilke – could spawn the Holocaust; that “Goethe’s garden almost borders on Buchenwald.”

In similar spirit, Timothy W Ryback’s fine study Hitler’s Private Library (2009) explores the sharp contrast between the Führer’s voracious reading and his genocidal totalitarianism. He was, as Ryback writes, “a man better known for burning books than collecting them and yet by the time he died at age 56 he owned an estimated 16,000 volumes”; claiming, at one stage, to read “at least one book per night, sometimes more.”

It would be absurd to argue that a person who has read the classics and keeps up to date with contemporary writing is axiomatically incapable of prejudice and xenophobia; as if literacy offered single-jab immunity against hatred. But, in a world governed by probabilities, it remains true that erudition tends to broaden horizons, challenge preconceptions and open minds that might otherwise be closed.

Put it this way. The oligarchs, the autocrats, and the tech tycoons; the theocrats, the sanctimonious literalists and the censors: what do they all have in common? They don’t want us to think. They want us to remain plastered on the soma they sell.

Suggested Reading

Racism in Britain is getting worse

They want us to be stupid. In that alone, there is a big clue to the radical potential of free, deep and thoughtful reading. In this setting, to be “bookish” is not to withdraw but to take a stand. Books are the rebel contraband of the idiot age.

As Malcolm X recalled in his autobiography: “I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life. As I see it today, the ability to read awoke inside me some dormant craving to be mentally alive.”

For the young Nye Bevan, books also represented a form of liberation. As Michael Foot writes in his biography of the founder of the NHS, the Tredegar Workmen’s Institute Library was an intellectual temple for the teenaged Bevan: “his reading became prodigious… He seized on everything and would often stay awake reading until the dawn. He wrote poems of his own and declaimed many more.”

This is why it is so infuriating when the campaign for reading is dismissed as a middle-class preoccupation or an elitist cause. The opposite is the case: it is precisely those who do not grow up in a household rich in intellectual capital who most deserve access to the full range of culture and knowledge. Why should books be the preserve of the affluent, a luxury rather than a basic entitlement at the core of modern citizenship?

In which context: few acts of social vandalism in the past quarter century match the closure of public libraries. According to a BBC report in March, the UK is losing these civic facilities at a rate of about 40 a year; in the past five years alone, 190 libraries have been shuttered.

Credit to Chris Kane, Labour MP for Stirling and Strathallan, for characterising public libraries in a Commons debate in May as “the NHS for the soul. They are funded by our taxes, free at the point of use and there when we need them the most.” Plenty applaud the sentiment. Few are willing to spend the public money required to give it force.

The most powerful foe of the reading habit, however, has been the digital revolution. What started as a text-based technology – one that promised to make everything ever written available, free of charge, to everyone – has become something very different, and all-consuming.

Bombarded by information rather than knowledge, driven by the algorithm towards content with which we already agree, coaxed to seek likes and clicks, we are suffering from species-wide attention deficit disorder. In 2018, the average human attention span was discovered by researchers to have fallen from 12 seconds in 2000 to only eight seconds – shorter than that managed by the average goldfish.

Even before the advent of the smartphone, widely available broadband and social media, the late novelist and essayist David Foster Wallace foresaw in a 2003 television interview what was coming: “Reading requires sitting alone, by yourself, in a quiet room. And I have friends, intelligent friends, who don’t like to read because they get – it’s not just bored – there’s an almost dread that comes up, I think, here about having to be alone and having to be quiet… When you walk into most public spaces in America it isn’t quiet anymore; they pipe music through.”

Now, 22 years later, we inhabit precisely the moronic inferno that Wallace described, a place in which noise and conflict and constant dopamine hits are at the basis of our cognitive diet. For the most part, the internet offers only ultra processed democracy; it has almost zero nutritional value.

Some have positively embraced this and dismissed reading as both hopelessly old-fashioned and a symptom of weakness. “I am not a fan of books,” said Kanye West in 2009. “I am a proud non-reader of books.” In 2022, before his conviction and imprisonment for fraud, conspiracy, and money-laundering, the crypto entrepreneur Sam Bankman-Fried said: “I’m very sceptical of books… I think, if you wrote a book, you fucked up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.”

In the same year, Andrew Tate went even further, tweeting as follows: “Reading books is for losers who are afraid to learn from life. So they try and learn from the life OTHERS have lived. But you never REALLY learn unless you lived it. You must feel it to believe it. Books are a total waste of time. Education for cowards.”

Three sub-optimal role models, for sure. Unfortunately, their philistinism is the spear’s tip of a more general inclination to see book-reading as a practice of the past, overtaken by generational and technological change. Ironically, however, it is the non-readers who are travelling back in time.

Evolutionary psychology and anthropology teach us that xenophobia was the default position of the self-sufficient village. Outsiders were seen as intrinsically threatening: importing violence, disease and “otherness”. But they also brought trade, technology, cultural exchange, and the collective resilience offered by inter-marriage. Across the millennia, human beings developed the cognitive habits that made them open to such interactions: the basis of civilisation.

Today, we live in the most complex, interdependent societies in history; taking for granted networks, supply chains and population mobility that make possible every aspect of modernity. At the same time – in a bleak irony – too many of us are forgetting or (never acquiring) the core cognitive skills of citizenship and co-existence. Ours is a world of quantum computing, nanotechnology and transformative AI; and yet, as a species, we are reverting in too many cases to the preliterate nativism of our distant ancestors.

Suggested Reading

First the flag. Now the poppy

Reading is not the whole answer, of course, but it is certainly part of it. To quote Bloom again, the company of books helps to “clear your mind of cant… the peculiar vocabulary of a sect or coven.” It encourages a sense of irony, which is at the heart of all constructive human interaction and the greatest enemy of ideology. Literacy melts literalism.

On which subject: I hope that the era of cancel culture is behind us. I was dismayed a few years ago to be told by the teenage daughter of a friend that To Kill a Mockingbird had been withdrawn from her school library because it was “racist”.

Banning books solves nothing, least of all the spread of prejudice. Is there any word more dismal in contemporary discourse than “problematic”? What does it even mean? To fight the right, we have to acknowledge the recent errors of the left. Respect for dissent is essential to respect for others. To read intelligently means engaging with diversity of opinion as well as diversity of author.

In this context, it is instructive that Everett has so vigorously defended Twain’s “wonderful novel” and encouraged readers to see his own book in conversation with the original. As he says: “My writing James is not in any way an indictment of Twain at all.”

Reading is not reclusive; it is not deferential, or ideologically conformist, or predictable in its immediate consequences. It sets free that most powerful of liberal forces, the human imagination, strengthens our capacity for doubt and encourages the curiosity that is the prerequisite of any truly open society. It is a psychic bungee-jump, a jail break from the prison of bigotry, ideology and linear thinking.

We should be encouraging it in schools, in the building of new libraries, and everywhere else. What Matthew Arnold famously called “the best that has been thought and said” should be available to all and celebrated as our common inheritance: not the quaint preoccupation of a diminishing number of antiquarians but a civil right in a pluralist society.

The battle against racism will be fought on many fronts. But this is one of them, and one that has been neglected for too long. To answer the challenge set by Atticus: to understand others, we can start by picking up a book.

Reading opens minds. It can change them. Turn the page on division and subscribe to The New World. Share our work, tell a friend, and be visible… buy the t-shirt (or the mug, or the hoodie). Go to shop.thenewworld.co.uk.

But most of all, read.