Robert Jay Lifton, one of the great public intellectuals of modern times, died last Thursday at the age of 99. As a pioneering psychological historian, Lifton chronicled the most terrible pathologies of the past century: the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Maoism, atrocities in Vietnam, the climate crisis, murderous cults and Covid.

One of his most important themes was “ideological totalism”, which he defined as “an extremist meeting ground between people and ideas”. In Losing Reality (2019), he described “the mental predators [that] are concerned not only with individual minds but with the ownership of reality itself.”

Such predators, he wrote, hate openness, pluralism and dissent; seek “milieu control”; demand purity; and redefine language: “all-encompassing jargon, prematurely abstract, highly categorical, relentlessly judging”. It was central to Lifton’s thesis that these ambitions were most pronounced in totalitarian regimes – but far from confined to them.

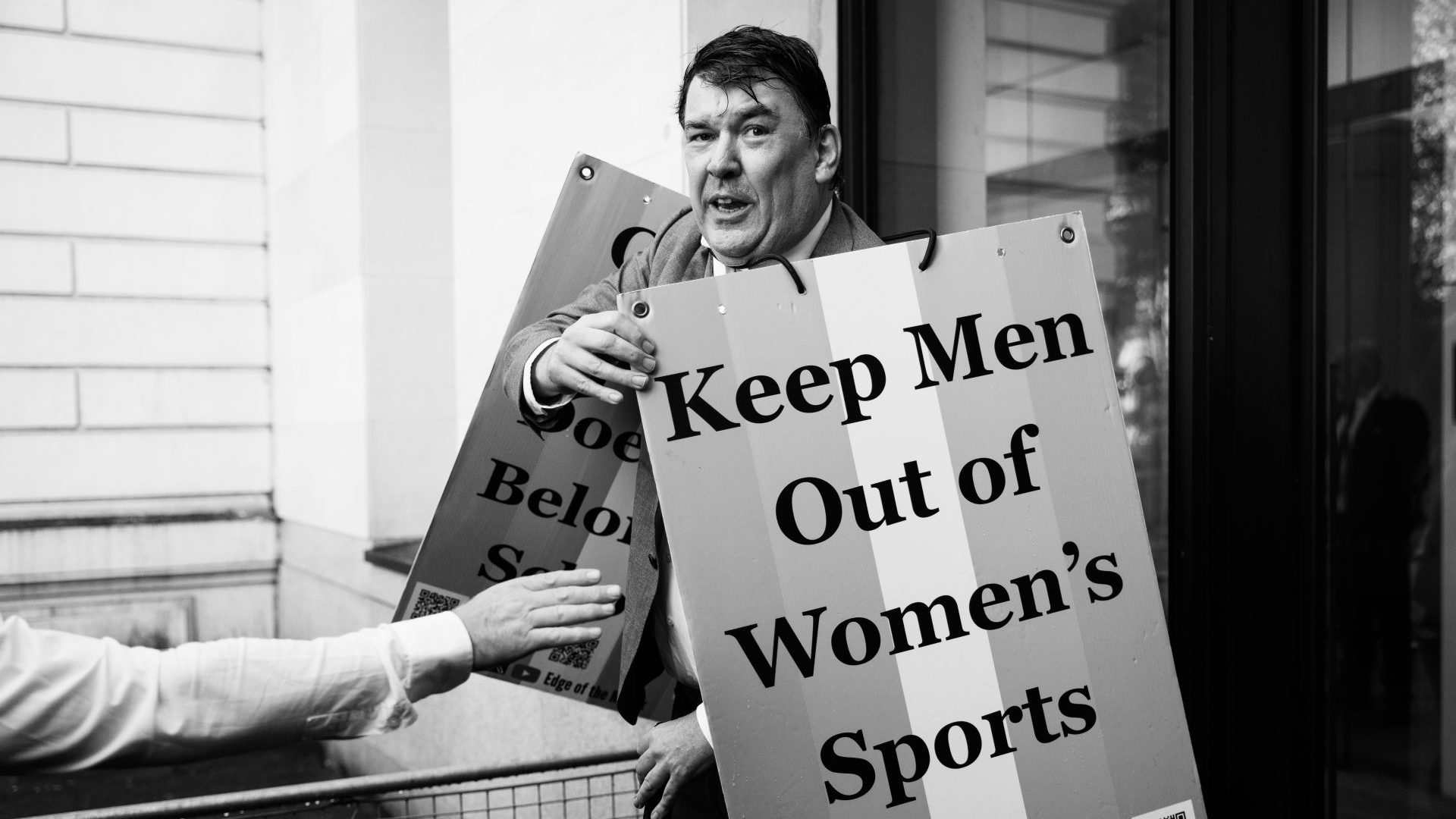

Which brings me to the arrest last Tuesday of the comic writer Graham Linehan by five armed police officers at Heathrow. As you probably know, his detention and questioning were the consequence of complaints about three of his tweets.

The most contentious of these was posted on April 20, in the aftermath of the supreme court’s landmark ruling that, in law, the word “woman” was defined by biological sex. Trans people were openly defying the judgment and the clear guidance from the Equalities and Human Rights Commission by posting selfies of themselves using women’s toilets. In response, Linehan posted on X: “If a trans-identified male is in a female-only space, he is committing a violent, abusive act. Make a scene, call the cops, and if all else fails, punch him in the balls”.

This was obviously facetious – Linehan’s natural register – but also, for the literal-minded, described a perfectly legitimate sequence of actions for women to take in self-defence, if biological males refused to leave their loos as the law required.

Sidenote: it was not until after the first world war that female toilets became widely available. Until then, women and girls were subject to what was horribly called the “urinary leash” – constrained by the lack of public facilities from walking too far from their homes. The right to female loos was indeed hard-won.

Among the many reactions to Linehan’s arrest my favourite was that of Zack Polanski, the new Green Party leader, who told BBC Five Live: “Should you be able to say that you want to kick a woman in the balls? No.” With insights like that, who can doubt that Zack has an exciting future on Strictly?

Step back for a moment to consider the wretched and muddled state of free speech in this country. As the New World founder and editor-in-chief, Matt Kelly, pointed out on The Two Matts last week, it is plainly absurd that hundreds of supporters of Palestine Action are now being arrested for expressing perfectly legitimate views about the Gaza conflict, while members of Homeland, the neo-Nazi breakaway from Patriotic Alternative that has done so much to stir up protests outside asylum hotels, can prowl the streets unchallenged.

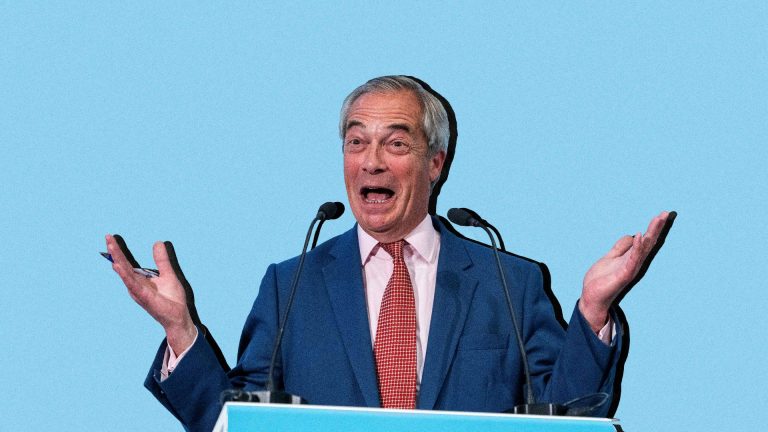

Meanwhile, Reform UK – which postures as a champion of free speech – had the temerity to exclude our Pulitzer-winning political editor, James Ball, from its party conference in Birmingham. It was indeed glorious last Wednesday to watch the (clearly well-informed) Jamie Raskin, Democratic representative for Maryland, reduce Nigel Farage to a blethering mess by asking him at the US House judiciary committee: “You’ve banned journalists you disagree with from your political events, haven’t you?” The Reform leader – apparently “unsighted”, as spin doctors put it – had no answer to this excellent question.

My first job in journalism was as a researcher at the free speech magazine Index on Censorship. At the time, the right to dissent, to create freely, to oppose orthodoxy was front and centre in political discourse: the cold war had just ended, the Rushdie affair was in the headlines, apartheid had recently collapsed.

In 2025, it is fair to say that – in spite of the continued efforts of that fine journal and other campaign groups – the cause of free expression is in pretty poor shape. In spite of the plentiful evidence from the 20th century that free speech is the first thing totalitarians and racial segregationists stamp out, it has become commonplace to look upon this particular liberty as – well – a bit analogue, a bit whiskery, a bit naff.

Not quite as bad as hereditary peerages or fox-hunting, maybe, but hardly a priority. At worst, during the “Great Awokening”, free speech was aligned by its detractors with white privilege – which would have come as a considerable surprise to Martin Luther King, John Lewis and Malcolm X.

A common explanation for this relegation is the transformative impact of digital media. True enough, we are now bombarded by a hurricane of online data, disinformation, rumour, and outright hatred. Is it any wonder (the argument runs) that our commitment to free speech is diminished?

I understand this point of view and, for what it’s worth, I continue to argue for digital regulation that fully enforces the laws governing speech (which is why I supported the conviction of Lucy Connolly for stirring up racial hatred on X during the Southport riots). But I think the effect of the digital revolution on free speech can also be framed in a very different way.

More than any medium in human history, the web – and social media, specifically – has enabled and turbocharged the collective human instinct to crush dissent. Not all censorship is enacted by the state. When hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of people are shaming you, when you are receiving death and rape threats in your direct messages, when companies shy of bad publicity choose cravenly to sack you rather than share the opprobrium – well, where stands free speech then?

Suggested Reading

The Reform party conference and the end of democracy

Linehan lost everything – career, marriage, reputation – for daring to support single-sex spaces, opposing the aggressive medicalisation of children’s anxieties, and arguing that biological males had no place in women’s sports. And what was so disgusting (no other word will do) is how his colleagues in the entertainment industry deserted him.

In his memoir, Tough Crowd (2023), he is kind enough to mention that I signed a letter drafted by him and the psychotherapist and author Stella O’Malley in support of JK Rowling in 2020, who was at the time, because of her gender-critical views, undergoing her transformation from National Treasure to Spawn of Satan. Much more important than mine were the signatures of literary giants such as Ian McEwan, Aminatta Forna and Tom Stoppard.

Most important of all, however, were those who didn’t sign; who were appalled that Linehan should even ask. Where, as he writes, were “my old buddies – the gunslingers, the iconoclasts”?

Where, for instance, was Linehan’s sometime friend Stewart Lee? Earlier this year, Lee said, not unreasonably, that he would not be touring Donald Trump’s America because he feared he might be “locked up”. A shame, then, that Lee so publicly consigned Linehan to his own so-called “pedal bin” for 2021.

This contradiction reflects two absurdities in contemporary liberalism. The first is the delusion that censorship or de-platforming or blacklisting is fine when nice people do it for nice reasons. As long ago as 1993, the US intellectual Jonathan Rauch warned in his extraordinarily prophetic book, Kindly Inquisitors (1993): “[W]hat about the day when right wingers get the upper hand? Will they be “fair”?… no one stays on top for long.”

In Trump’s America that premonition is becoming horribly true. But the president’s path was smoothed by the indifference the liberal left showed towards the speech they didn’t like. It became almost fashionable to condemn the First Amendment as the work of white supremacists and well past its sell-by date. How’s that argument working out in 2025?

The second absurdity is aesthetic and behavioural rather than ideological. Not to put too fine a point on it, too many liberals have forgotten that progress is an untidy, scratchy business and often – in fact, always – involves people who are obnoxious, blunt and intemperate. They confuse docility with decency, a quiet life with a good life.

They want a Jo Malone democracy: smooth, beautifully scented, free of abrasiveness. Ask this kind of liberal whether he wants coffee or tea, and he’ll say: “Why can’t we all just get along?”

The row over trans ideology and women’s rights has been a parable of this collective cowardice. Too many people in positions of influence were worried that things that needed to be said might be “toxic”: a word that has been debased into near-meaninglessness.

A common holding position for split-the-difference liberals was to mutter that there was “fault on both sides”. But, as Linehan has written: “Women have never surrounded a meeting of trans-identified people, they have never sent violent death and rape threats to trans-identified people. Women write essays and make arguments. Women gather to speak to other women. Women place stickers reading ‘ADULT HUMAN FEMALE’ on lampposts; they don’t nail dead rats to doors, or post death and rape threats to the authors of children’s books.”

When the Supreme Court announced its ruling, feminists were widely condemned by the bien-pensants for daring to celebrate with a glass of champagne. Rowling was chastised for posting an image of herself smoking a cigar. I don’t recall comparable condemnation of the trans activists waving placards with slogans calling for the death of Terfs (“trans exclusionary radical feminists”).

Suggested Reading

Two speeches, 20 years apart, show Starmer how to tackle Farage

One has to hand it to the trans ideologues: they had a good run, and they’re not done yet. With particular cunning they grasped that, in the hyper-modern world, the aspiring “totalist” who wished to suppress inconvenient speech could bypass the old street-level methods of civil rights activists and proceed directly to institutional colonisation: political parties, the professions, the corporate world, charities, publishing, cultural organisations, the progressive media.

All were captured in what the US political scientist Yascha Mounk has aptly called the “short march through the institutions”. As a consequence, crucially, there was never an informed debate about the manifest problems involved with the preservation of single-sex spaces, women’s sports, and the scandal of “gender-affirming care” (a euphemism for the fast track to life-altering medication and, in many cases, surgery).

Those like Linehan and the many courageous feminists who fought for years to keep rationality alive faced job loss, arrest, vexatious civil litigation, and physical danger. They were excluded from as many roles, cultural events and platforms as their opponents could think of: all in the name of “kindness”.

Not until the Cass Review into the Gender Identity Development Service at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust in north London and the Supreme Court ruling did Labour suddenly pretend that it had always been opposed to the medicalisation of gender dysphoria in children and had never doubted for a second what the word “woman” really meant. This was stomach-churning to hear.

Such speech perfectly matches George Orwell’s definition of political language as “designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”. In September 2021, Keir Starmer scolded Rosie Duffield, when she was still a Labour MP, for pointing out that only a woman can have a cervix. “It is something that shouldn’t be said,” he insisted. “It’s not right.” Shouldn’t be said. Great work from Mr Human Rights.

Linehan did say such things, and much else besides. He is bolshy, defiant, difficult. These are qualities that make many progressives clutch their pearls and recoil from him. In truth, they are precisely what make him so consequential a figure, and such a breath of fresh air in the precincts of the prim. Heresy is much more precious than consensus.

It is a grave error to confuse polarisation and division. Polarisation is what we have now: ideological cantons and safe spaces in which the like-minded snuggle up to one another and complain about the terrible people on the other side of no-man’s-land.

Division is what happens when people dare to question and stand up to one another. Division – one hopes – leads to resolution and social concord. It must be peaceful. But it cannot be avoided. And free speech is the most powerful solvent of nonsense, stupidity and injustice.

Forty years ago, in his great essay An Anatomy of Reticence, Václav Havel identified the necessity of such speech: “A trace of the heroic dreamer, something mad and unrealistic, is hidden in the very genesis of the dissident perspective… [The dissident] writes, cries out, screams, requests, appeals to the law – and all the time he knows that, sooner or later, they will lock him up for it.”

They did lock up Linehan, “in a small green-tiled cell with a bunk,” before releasing him on bail. Those whom Lifton called “totalists” will keep trying to limit what he, and we, can say and think. Which is precisely why we need more people like this irascible Irishman.

That’s democracy for you. If it’s comfortable, it isn’t working.