PICK OF THE WEEK

Caught Stealing (general release)

The movies of Darren Aronofsky are like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates: you never know what you’re gonna get. For every Requiem for a Dream (2000) or Black Swan (2010) there’s a Noah (2014) or Mother! (2017).

Happily, Caught Stealing is a very entertaining gangland caper, high-octane with a high body count to match. In New York in 1998, Austin Butler is Hank Thompson, a former baseball prodigy whose pro career was wrecked in a car crash before it began. Now he is a booze-drenched barman who breakfasts on cold beer, talks to his mother on the phone every day (“Go Giants!”) and is uncertain whether he should commit fully to his paramedic girlfriend Yvonne (Zoë Kravitz).

The trouble starts when Hank’s British neighbour Russ (Matt Smith, with magnificent punk mohawk) claims that his father is ill and asks him to look after his cat Bud, a spirited Maine Coon. No sooner has Russ done a runner than two Russian bad guys – Aleksei (Yuri Kolokolnikov) and Pavel (Nikita Kukushkin) – turn up and beat Hank so badly that he has to have a kidney removed.

Next up is Puerto Rican mobster Colorado (Benito A Martínez Ocasio, aka rapper Bad Bunny), who wants whatever it is that he thinks Hank is looking after while Russ is on the lam (the McGuffin is a mysterious key, hidden in Bud’s litter tray). Assigned to the case, Detective Roman (Regina King) is spectacularly unsympathetic to the luckless barman and concedes that she is “fucking with” him. For fun, or with an ulterior motive?

The best and scariest villains are the Hasidic brothers Lipa (Liev Schreiber) and Shmully (Vincent D’Onofrio), who, having abducted Hank, take him to Shabbos dinner at the home of their mother Bubbe (Carol Kane). She warms to her unexpected guest but – sensing he is out of his depth – warns him not to show his teeth if he isn’t going to bite.

With the gritty aesthetic of a 1990s crime movie, Caught Stealing (a baseball term, apparently) is a love letter to New York, from the mean streets of the Lower East Side via Flushing Meadows to Brighton Beach. It is also a homage to Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) – not by accident does Griffin Dunne play Hank’s coke-snorting boss, Paul, sporting a long grey ponytail.

The growing bond between Hank and Bud is a nod to the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis (2013). And there are explicit references to The French Connection (1971) throughout.

All of which is to say that Aronofsky – who tends to miss the target when he over-conceptualises – is having the time of his life. It is infectious.

THEATRE

Born With Teeth (Wyndham’s Theatre, London, until November 1)

For almost a decade, it has been broadly accepted by literary scholars that William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe collaborated on the former’s Henry VI trilogy. And it is from the third of those history plays that Liz Duffy Adams drew the title of her own drama, now receiving its London premiere (Richard of Gloucester, the future Richard III, says that at the moment of his birth, the midwife cried out: “Oh Jesus bless us, he is born with teeth!”)

Ncuti Gatwa, who bowed out of Doctor Who in May, is electrifying as Marlowe: a literary star, sexual adventurer and spy for Robert Cecil. Edward Bluemel’s Shakespeare is more circumspect than his artistic rival, though deeply attracted to him as mentor, creative partner and prospective lover. The two men flirt, dance and prowl around one another in a compelling contest of power, talent and lust.

In the perilous world of Elizabethan court intrigue, there are informants and “intelligencers” lurking behind every arras. Religion is the deadliest subject of all, and Marlowe is wise to the Catholicism in Shakespeare’s background. Yet he himself edges towards outright atheism, and scoffs at his protégé’s belief that God is to be found in the “ineffable”.

The tension is sexual, creative and political: will Shakespeare’s patience serve him better than Marlowe’s recklessness? Directed by Daniel Evans for the Royal Shakespeare Company, this is theatre at its most compelling – confirming, above all, that Gatwa (also seen in Jay Roach’s new movie, The Roses) is a once-in-a-generation talent who deserves all the accolades that will surely come his way.

Suggested Reading

When will Quentin Tarantino shut the f*** up?

STREAMING

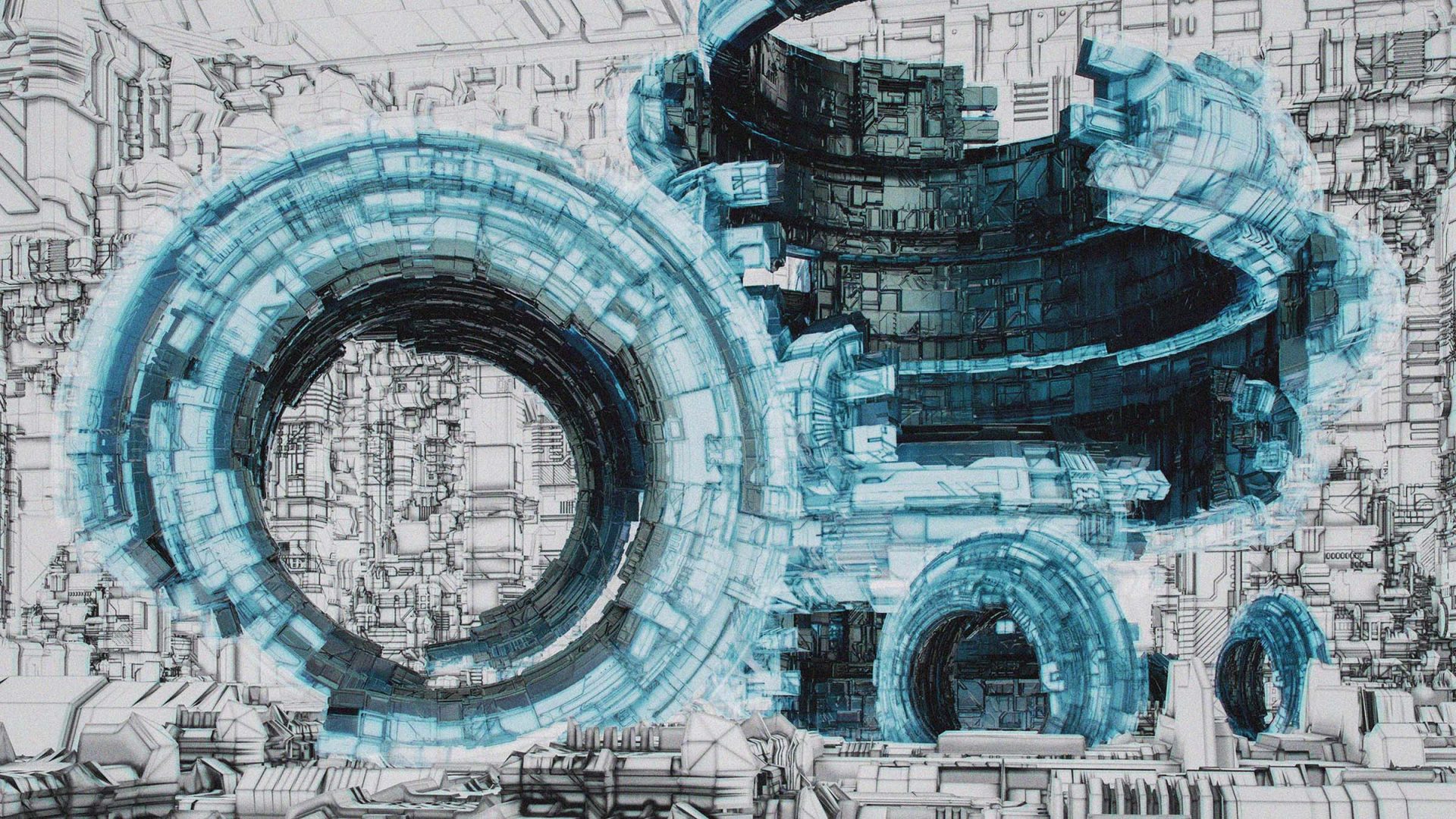

Alien: Earth (Disney+)

The first scene of Noah Hawley’s television adaptation of the long-running movie franchise so uncannily recalls the opening of Ridley Scott’s 1979 original that even the most cynical viewer may feel a pang of optimism. Seven movies in – not counting the two ghastly Predator crossovers – it is hard not to be wary. But Hawley, the master showrunner behind Fargo and Legion, truly delivers.

It is 2120, two years before the crew of the Nostromo makes its terrible discovery on LV-426 and John Hurt’s chest explodes. The governance of Earth is divided between five mega-corporations – Weyland-Yutani, Dynamic, Lynch, Threshold and Prodigy – the last of which is the creation of the youngest-ever trillionaire, Boy Kavalier (Samuel Blenkin). On Neverland, his island research fortress, this unlovable Young Elon is transplanting the identities of dying children to “hybrid” machines; starting with Marcy (Florence Bensberg) who, in her new adult body becomes Wendy (Sydney Chandler).

At his side is chief scientist Kirsh (Timothy Olyphant), a synthetic whose bleached hair recalls the replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) from Scott’s other early sci-fi masterpiece, Blade Runner (1982). Human, but no less glacial, is chief of staff Atom Eins (Adrian Edmondson, who played Vyvyan in The Young Ones – a show unexpectedly revered by Hawley).

When the USCSS Maginot, the Weyland-Yutani C-class deep space research vessel from the opening sequence, crashes in New Siam, a city controlled by Prodigy, Kavalier deploys Wendy and her fellow superstrength hybrids to capture its precious cargo: five alien specimens, including, but not confined to, the classic xenomorph. In a nod to James Cameron’s Aliens (1986), a unit of soldiers – amongst them Wendy’s medic brother Joe Hermit (Alex Lawther) – is already on the scene and blasting.

Will Joe believe that his sister, whom he believes dead, has survived in an artificial body? How is the Maginot’s surviving security officer, the cyborg Morrow (Babou Ceesay), planning to retrieve the specimens? And what is that thing with a huge, deformed eye?

In its relish for old-school sci-fi body horror, sheer pace and respect for its source-material, Hawley’s eight-episode series is – against all odds – the best chapter of the Alien saga since the face-hugger first leapt from its egg.

BOOK

Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy, by Peter Jeffreys & Gregory Jusdanis (Summit Books)

Though many of his poems have entered the literary canon – especially Waiting for the Barbarians (1904), The City (1910) and Ithaca (1911) – CP Cavafy (1863-1933) himself has not attracted the attention that is his due. This fine biography, the first in English since Robert Liddell’s more than half a century ago, is therefore a welcome corrective.

Born into an affluent family of merchants, the young Constantine’s life was disrupted by the sudden death of his father Peter John in 1870; after which his mother, Haricleia, moved the family from Alexandria to England, where they lived in Liverpool and London. After a spell in Istanbul, he returned to Alexandria for good in 1885.

Cavafy’s relative obscurity in the pantheon today has two principal origins. First, his work was mostly circulated in private before his death – though, in the 1920s, TS Eliot published initial translations in The Criterion, profoundly influencing younger writers including W.H. Auden. Not until 1951 did Leonard Woolf publish the first English-language volume of his poetry.

Second, his homosexuality, though “obscure only to the ignorant” as he put it, made him wary of the limelight. It was one of the engines of his creativity: “In the dissolute life of my youth/ The designs of my poetry took shape,/ the territories of my art took form”. But he led a relatively quiet life as a clerk at the office of irrigation services for three decades, confining himself to a private literary salon in his flat at 10 Lepsius Street where he could elaborate to his circle of admirers upon his fascination with the fate of civilisations, his passion for mythology and his contempt for adjectives.

That said, Cavafy, as the authors note, also behaved like a man who “expected someone to write his life story”, obsessively hoarding every record “from his entry card to the Alexandria stock exchange, to theatre tickets, drafts of letters, lists of things to do”. He sensed that posterity would be intrigued, and this thematically organised study restores to full and vivid life the writer who, as his friend EM Forster put it, was “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.”

STREAMING

Talking Pictures: The Godfather Trilogy (iPlayer)

A crisp 45-minute introduction to Francis Ford Coppola’s towering achievement which is still worth watching even if you think you have heard it all before. This BBC Four series makes intelligent use of archive interview footage to frame great movies – and, in this case, has plenty of material to choose from. I had not seen Robert Duvall saying quite so openly that he refused to return as Tom Hagen, the Corleone family’s consigliere, in The Godfather Part III – to the detriment of the movie – because he wasn’t offered enough money. It is also striking that, as mighty as the ensemble cast and production team undoubtedly were, all the interviewees (Robert Evans, Al Pacino, Diane Keaton and others) categorically ascribe the greatness of the films to Coppola’s genius.