1. You could argue, if you wanted to get all philosophical about it, that the Great Wall of China doesn’t really exist. The name, after all, implies a single, enormous thing, but what northern China actually has is a whole web of different sorts of defensive structures – ramparts and fortresses, yes, but also trenches and ditches, even stretches formed by natural features such as rivers and hills. How much of this actually counts as “Great Wall” is a matter of some debate.

2. For this reason it’s surprisingly difficult to pin down anything as useful as a length. For many years, the most wall-like bits of the wall, the Ming Walls, were thought to stretch roughly 6,700km (4,160 miles) from Gansu province of the far north west, to the Shanhai Pass in Manchuria in the north east. In 2009, though, the Chinese government announced that satellite imagery and better calculations had turned up another 2,150km of wall – which feels like quite the underestimate.

3. In 2012, the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China concluded that the remaining “Great Wall-associated sites” – 10,051 wall sections, 1,764 ramparts or trenches, 29,510 individual buildings, and 2,211 fortifications or passes – came to an admirably specific total length of 21,196.18km. These obviously don’t make up a single line – but if it did, it’d reach more than halfway around the equator, or from Beijing to Patagonia.

4. Even that may be an underestimate. Unesco, which has ranked the wall as a World Heritage Site since 1987, claims there are over 50,000km of walls – although that must surely be counting stretches that no longer exist, and by this point I must say I am becoming a little cynical about some of these figures.

5. The oldest of the walls date from the 7th century BCE when the state of Chu, centred in today’s Hubei province, began building the “Square Wall” to defend its capital. Over the next few centuries, assorted rival powers – the Qi, the Zhongshan, the Wei, the Qin – all built their own walls. The fact that the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE are remembered as the “Warring States period” may offer some clue as to why.

6. In 221BCE, the Shihaungdi Emperor – the first real emperor of China – came to power by unifying the country and claiming his Qin dynasty would last 10,000 generations. That proved a bit optimistic – after his death in 207BCE it survived just four years, so a more accurate prediction would have been “not quite one generation” – but before that happened he did oversee the unification of China’s written script, the standardisation of its weights and measures, and all sorts of other state-building things.

7. These included an enormous programme of public works: roads, canals, fortresses, and a major project to link sections of existing fortification into the “10,000-Li Long Wall” (a li is approximately 500m) to keep out the nomads who lived in the wastes to the north. There’s a lot of sad poetry from this period about young men being conscripted to build the wall and never coming home again. Untold numbers died; some, it is said without evidence, were literally buried in the walls.

8. Most of these early walls are earthworks rather than walls in the sense we’d generally understand. The wall you’re likely imagining – a grey stone line following the line of hills to the horizon – are the aforementioned Ming Wall, which that dynasty built in the 15th and 16th centuries to prevent a repeat of the Mongol invasions of the 13th. That worked, in so much as the Mongols never invaded again, but it did not prevent the Qing invasions from Manchuria in the 17th century – or, come to that, Europeans showing up with gunships in the 19th.

9. Despite the cliche, you can’t see the Great Wall of China from space with the naked eye, alas. Partly this is because it is often made from materials found in the local environment, and is thus a similar colour to the ground around it; but mostly it’s because it’s only about five metres wide, and it’d be like trying to spot a single hair on 34th Street from the top of the Empire State Building. The best place to see the Great Wall of China is still, almost certainly, China.

Suggested Reading

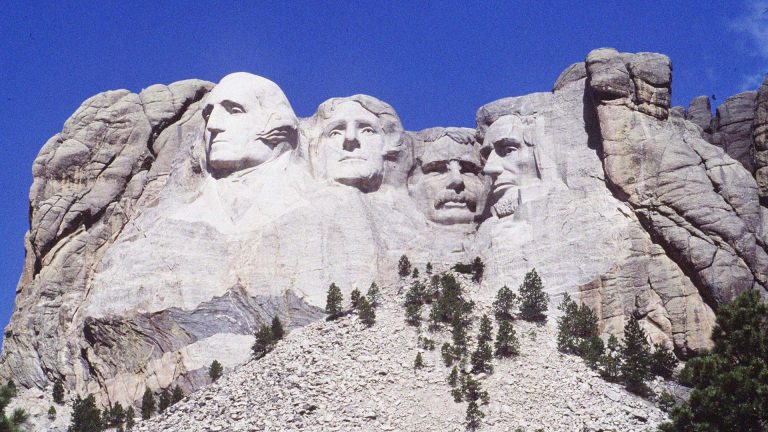

Nerd’s Eye View: 14 things you need to know about Mount Rushmore

8,850

Length (km)of the Ming Walls, the most wall-like section

7.8m

Estimated average height of the walls

1987

Recognised as a Unesco World Heritage site

2007

Voted one of the New Seven Wonders of the World

10 million

Annual visitors to Badaling, the most popular section