1. In pre-colonial times, Venezuela – on the northern coast of South America – was home to the Carib, Arawak and Chibcha peoples. The region was first visited by Europeans in 1498, on Christopher Columbus’s third journey to the New World, and first colonised by Spanish settlers from 1521.

2. Its name – literally “Little Venice”, like that posh bit of north-west London – is a reference to the fact some of the locals lived in houses on stilts above water.

3. The region was nearly, unexpectedly, German: in the mid-16th century, a banking house from Augsburg purchased exploration and colonisation rights – the sort of thing rich Europeans were cheerfully selling each other in those days. But it didn’t come off, and from 1546 Spanish explorers began to arrive in the hope of finding El Dorado, the mythical city of gold.

4. In 1810, with Madrid distracted by a slight Napoleonic invasion, the good burghers of Caracas took the opportunity to declare independence from the Spanish empire. It took over a decade of war, a couple of republics and quite a lot of territorial chopping and changing, but in 1821, the north of South America (plus a bit of Central America) had been recognised as the new independent state of Colombia. Nine years later, Venezuela and Ecuador declared their independence from that, too.

5. Incidentally, the president of Gran Colombia – as historians tend to call that short-lived state, to distinguish it from its still extant namesake – was the revolutionary commander Simón Bolívar, a Caracas native of European descent. Oddly enough, the region to which he would give his name was not Venezuela or any other part of Gran Colombia, but another patch of land nearly 1,500 miles south across the Amazon basin: Bolivia.

6. In 1899, the provincial General Cipriano Castro arrived in Caracas with an army from his Andean home state of Táchira, and seized the presidency. A succession of five such Táchiran military strongmen would control the nation for most of the next 59 years. The only break came when a 1945 military rebellion resulted in, variously, a coup, a new constitution, the first democratic elections in 1948 and, just eight months later, another coup which brought the fifth and last Táchiran strongman to power.

7. One oft-cited explanation for Venezuela’s tendency towards authoritarian instability lies in the fact that, in 1922, geologists from Royal Dutch Shell had discovered quite an incredible amount of oil there. Petrostates are prone to what is known as the “resource curse”: states funded via exports rather than taxes have weak ties between government and governed, fuelling authoritarian power grabs and corruption. Vast inward capital flows also lead to currency appreciation and underinvestment in other economic sectors, and leave their economies highly vulnerable to unpredictable swings in global energy prices.

8. So Venezuela has frequently been the site of insurrections, uprisings and revolutions. Democracy was not established with any firmness until after the 1958 coup; the presidency was not transferred from one civilian to another until 1964, and not from one party to another until 1969.

9. The first of the two failed coup attempts of 1992, incidentally, was the first event to bring a young military officer named Hugo Chávez to national attention. (The second that year was also held by officers loyal to his Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200, but Chávez himself was in prison at the time.)

10. Chávez eventually became president the boring way, winning the 1998 election on a wave of disenchantment with the establishment and anti-US feeling. His “Bolivarian Revolution” used oil revenues to combat poverty through improved access to food, housing, healthcare and education. But he was also accused of democratic backsliding, attacks on free speech and, through land reform, undermining private property.

11. What’s more, his social programmes were entirely dependent on high oil prices – and within a few months of Chávez’s death in 2013 from cancer, oil prices began to plunge, from over $100 a barrel to just $30. As a result, his successor, Nicolás Maduro, soon presided over a 75% contraction of GDP, soaring debt and inflation reaching (this is not a typo) 130,000%.

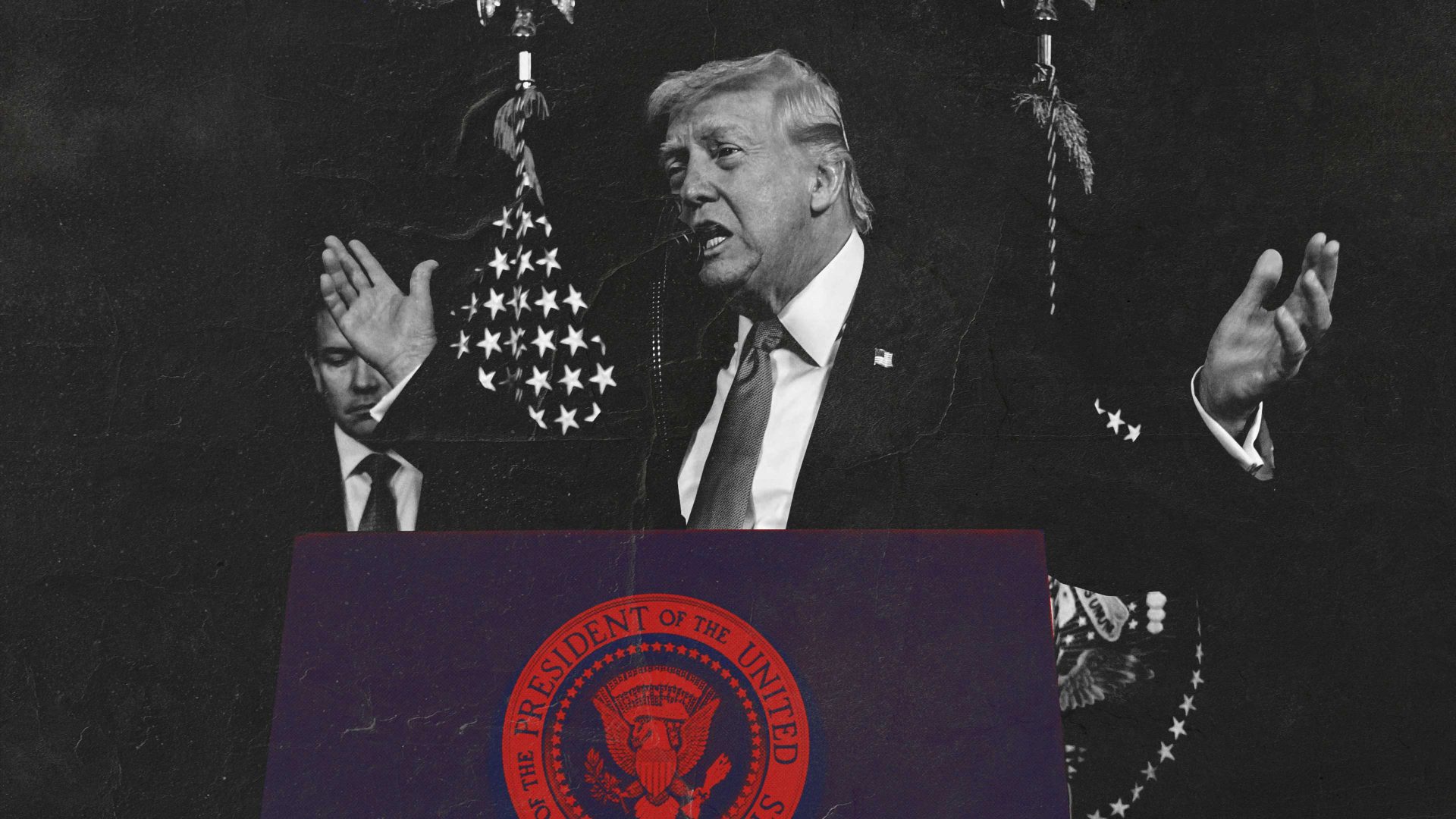

12. Maduro began his third term last January after being declared winner of the July 2024 presidential election. That, though, was the second election running whose legitimacy was questioned by the international community, and the third by the opposition (whose criticisms of an election not generally questioned by outside observers surely raises questions in itself). From 2018 to 2022, many countries instead recognised a government in exile headed by Juan Guaidó. Those who did recognise Maduro included Russia, China and Iran.

13. At any rate, the combination of collapsing social spending, economic crisis and US sanctions have led to declining oil production, severe shortages of basic goods like food, medicines and drinking water, and nearly 8 million people – around a quarter of the population – fleeing the country as refugees.

14. It’s far from clear that any of this is enough, even slightly, to justify the breach of international law represented by another government simply kidnapping Maduro to force regime change.

Suggested Reading

Nerd’s Eye View: 13 things you need to know about the New Year

916k

Size of Venezuela in square kilometres – larger than France and Germany combined

29m

Population of Venezuela. The figure is inherently approximate, because…

8m

… nearly 8 million people are believed to have fled as refugees

1908, 1945, 1948, 1958

Dates of successful coups in Venezuela

1992, 2002

Dates of unsuccessful coups in Venezuela