1. For most of history there were no legal restrictions on who could enter or leave the UK or its predecessor states. International travel was a lot slower and pricier than today, making migration a relatively difficult affair for anyone who didn’t have an empire to build.

2. That only changed with the Aliens Act 1905, which gave the home secretary power over immigration for the first time, allowed the authorities to turn people away on medical grounds, and declared those who “appeared unable to support themselves” as “undesirable”. The act was widely seen as a response to two decades of Jewish migration from eastern Europe. Opposition led Winston Churchill to cross the floor to the Liberals.

3. Postwar, the government hoped migration from Europe would plug gaps in the labour market. But existing relationships, combined with the British Nationality Act 1948 – which made a combined “Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies” (CUKC) the only form of citizenship in that realm – meant that most incomers actually came from the empire. The 802 people who arrived from the Caribbean on the Empire Windrush became symbolic of an entire generation of migrants – which is why it’s the only former Nazi troopship (yes, really) mentioned on the London tube map today.

4. From the early 1960s, governments gradually eroded the automatic right of Commonwealth citizens to settle in the UK. Rules requiring work vouchers were introduced in 1962, and requiring proof of British ancestry in 1968; repatriation assistance, and the replacement of work vouchers with temporary permits, in 1971. Some of these measures were meant to bring Britain in line with the European Economic Community, to prepare for membership and the free movement of labour. Others may have had less noble motives.

5. The government only started tracking immigration figures in 1964, through the international passenger survey. For the next two decades, net migration was consistently negative, thanks to schemes encouraging emigration to Canada, New Zealand or Australia. Notably among the latter was the “ten pound pom” scheme, used by 1.5 million Britons including Julia Gillard and the Bee Gees. It was only after 1983 that net migration consistently moved into positive numbers – though even then, a recession could reverse it.

Suggested Reading

The crazy right will never be satisfied about migration

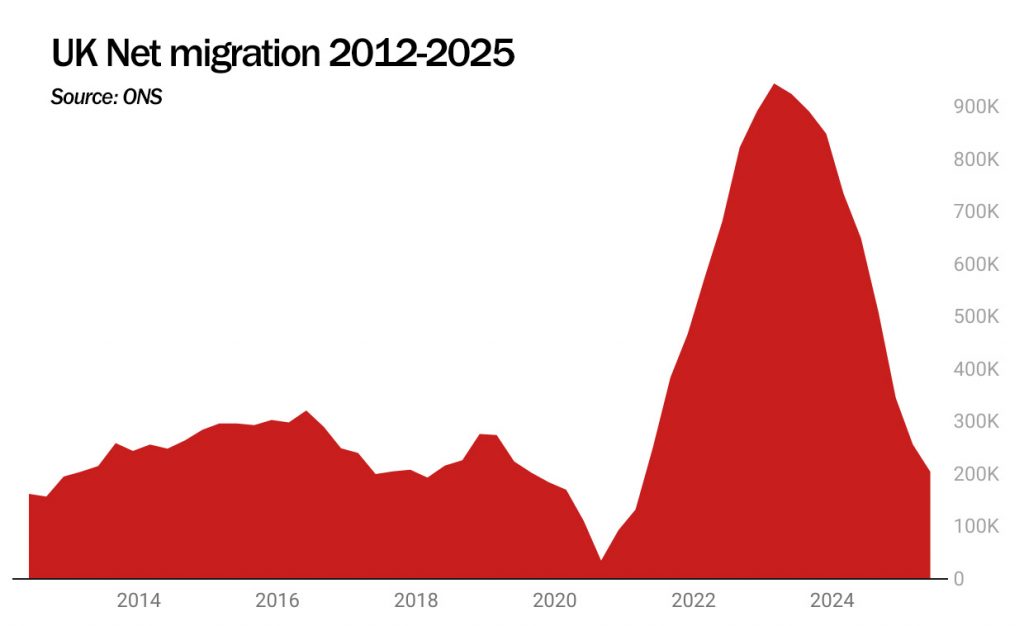

6. The newly created EU replaced freedom to work abroad with full freedom of movement in 1993. But European migration to Britain only really boomed after 2004, when Britain – along with Ireland and Sweden – declined to implement transition controls on migrants from the new eastern European member states. That number only fell again after we voted to tell Europe to piss off in 2016 – funny, that – then went into negative numbers after 2022.

7. Anyone who read “take back control” as “turn back the clock”, however, will have been disappointed: the gap left by European migration has been more than filled by migration from the rest of the world. Part of the explanation lies in two big humanitarian crises: in recent years, roughly 175,000 people have arrived from Hong Kong, and 270,000 from Ukraine.

8. But the bigger impact came from the points-based immigration system introduced by the Johnson government. Those who’d promoted such a system, influenced by the one used in Australia, expected it to reduce migrant numbers. The problem was that, because parts of the British economy, like health and social care, faced significant labour shortages, a system based on actual need meant the number of people qualifying for visas reached record highs. Particularly helpful parts of the right have sometimes called this phenomenon the “Boris-wave”.

9. Student migration has also soared, as struggling universities have used pricey degrees for foreign students to subsidise flat-lining domestic fees.

10. A reduction in immigration is a lot easier for ministers to promise than to actually deliver. So it is remarkable that, in 12 months, the Labour government has got immigration down by two thirds, to 204,000. That’s 80% down on its 2023 “Boris-wave” peak. A word

of caution for No 10 – while polls show voters want migrant numbers reduced, they also show support for current or even higher levels in many sectors, including students, health and social care, and, unexpectedly, public transport drivers.

11. Incidentally, in the 1960s and 1970s, when net migration was running at minus 50,000 a year, more than 85% of Britons still thought immigration was too high.

80%

The amount immigration to the UK has fallen since the “Boris-wave” of 2023

1.5m

Number of Britons who took advantage

of the 1945 ‘ten pound pom’ scheme to emigrate to Australia

85%

Proportion of Britons who thought immigration was too high in the 1970s – when it was running at minus 50,000

175k

Arrivals to UK from Hong Kong since Brexit. 270,000 people have fled the war in Ukraine to come here