1. In 2024, “sewage spills” – incidents in which Britain’s ever-popular water industry discharged human waste products into its rivers, lakes and seas – hit record levels. In England alone, the total duration of all sewage spills last year stood at 3.6 million hours, slightly up from the 3.6 million in 2023 (you’ll just have to trust me that, before rounding, it’s a smaller number), and more than double the 1.8 million in 2022.

2. This is particularly unnerving, given that there are only 8,760 hours in a year. Contemporaneous spills from 15,000 different overflow sites are counted separately. When you consider a maximum possible score of around 131.4 million hours, suddenly that 3.6 million doesn’t look so bad.

3. The reason this happens is because the UK has a “combined sewerage” system, in which rainwater and wastewater – from kitchens or bathrooms, households or commercial premises – travel to the treatment works in the same pipes. During periods of heavy rainfall, the system is designed to release wastewater directly into the environment to prevent the pipes from becoming overwhelmed and causing floods.

4. Historically, that worked fine; recently, though, extreme weather events (large storms; periods of rain landing on dried-out ground that can’t absorb it) have become significantly more frequent. Alas, investment to help manage such events has become, if anything, less frequent. And so incidents in which the public have found themselves in close proximity to polluted water have increased, too.

5. This is a problem, because human poo in water can expose people to gastroenteritis (spread by bacteria like salmonella or E.coli) or liver damage (hepatitis A).

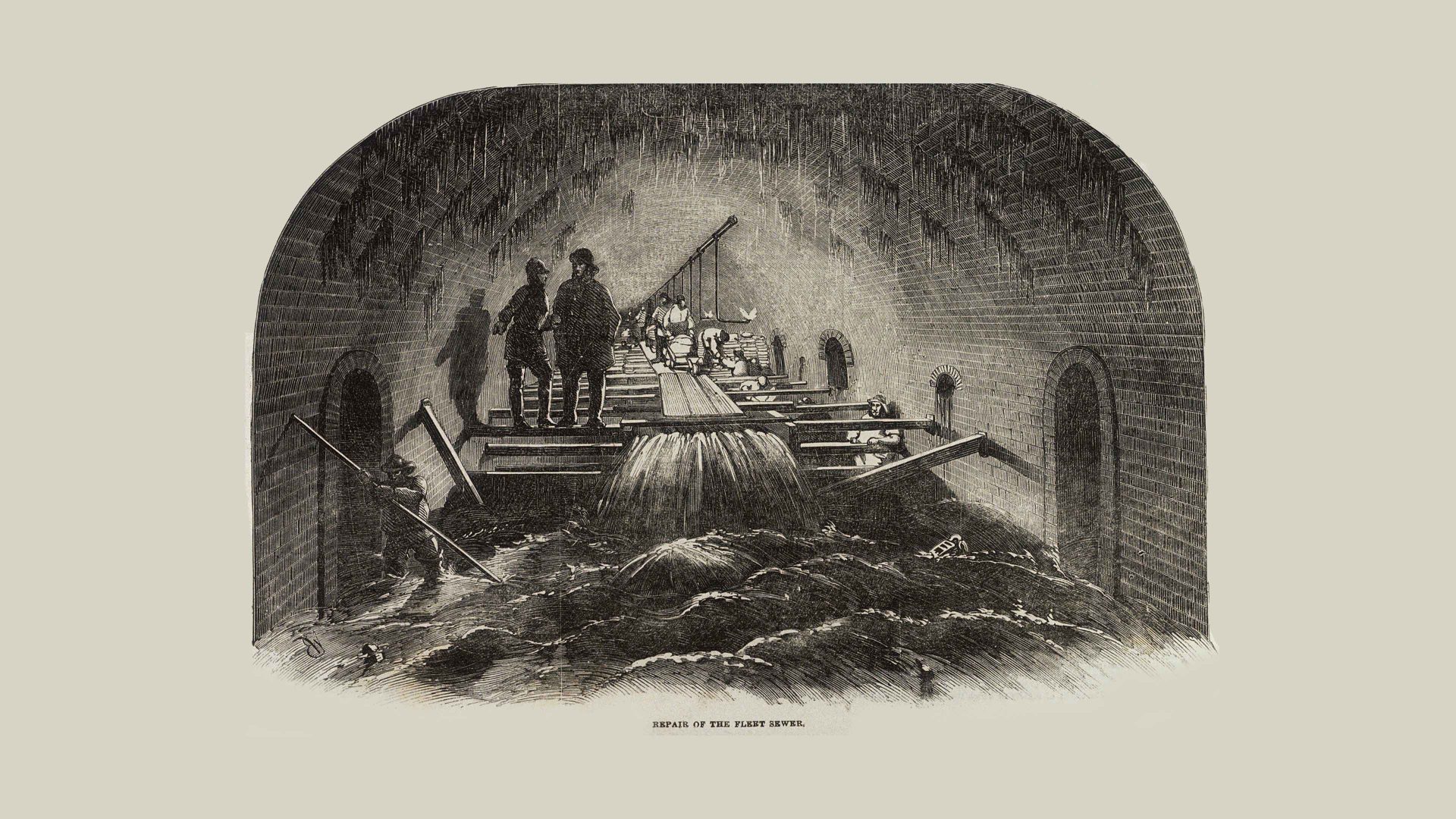

6. None of this is new information. For much of history, human waste products were disposed of either directly into watercourses where they could naturally disperse, or dumped into cesspits, where they’d occasionally be emptied by “night soil men”. This was fine when settlements were small – but in the 19th century, both urban populations, and the volume of their waste products, exploded.

7. In 1854, as London dealt with its third cholera outbreak in less than 25 years, a physician named John Snow disproved the miasma – “bad air” – theory of disease, by mapping the cholera deaths in Soho (pictured). He traced the outbreak to the Broad Street water pump, which sat atop a well sited a bit too close to a nearby cesspit. Snow’s legacies include germ theory, epidemiology and the name of a nearby pub.

Suggested Reading

Nerd’s Eye View: 15 things you need to know about the planets

8. The thing that spurred politicians to action, though, was not the death of poor people, but a terrible smell. A heatwave in the summer of 1858 exacerbated the smell of all that lovely sewage bubbling away in the Thames next to Parliament, an incident remembered as the “Great Stink”.

9. To make sure it didn’t happen again, the government backed a plan by Joseph Bazalgette to build London an extensive new sewer system. Giant “outfall” sewers would ferry waste downriver, to Beckton in Essex and Crossness in Kent, where it could be released without bothering the population of London. As a bonus the capital got the Victoria, Albert and Chelsea Embankments, too.

10. That still meant dumping untreated waste into the river only a few miles from London, of course – at a point, indeed, well inside the capital’s boundaries today. This became a problem on September 3, 1878 when the SS Princess Alice, a paddle steamer on its return journey from the Rosherville Pleasure Gardens near Gravesend, collided with a cargo ship named the SS Bywell Castle in the stretch of river known as Barking Reach, broke into three pieces and sank.

11. All this happened so quickly that few of those below deck made it off the ship: a diver who visited the wreck later reported that passengers were still jammed upright in the doorways, where they’d died trying to escape. But most of those who did make it out literally drowned in raw sewage. Exactly how many passengers died that day is impossible to know – local passenger steamers didn’t take roll-call, any more than a local train service does today – but it’s believed to be between 600 and 700, nearly half as many as drowned on board the Titanic.

12. Following an inquest, the Metropolitan Board of Works began to treat sewage at Crossness and Beckton, then transport it on “sludge boats” to be dumped into the North Sea. The practice only ceased in 1998.

13. Incidentally, the water company responsible for the highest total of sewage spills – 56,173, lasting an average of 10 hours each – was South West Water. In August it was shortlisted for the Biodiversity Challenge Awards 2025.

1858: Joseph Bazalgette set out to build London a proper sewage system

3.6m: Total hours of sewage spills in the UK last year

75: Number of serious pollution incidents, involving threat to aquatic or human health

81%: Proportion of these that came from just three companies: Thames Water (33 incidents), Southern Water (15) and Yorkshire Water (13)