I have never understood the prevailing view of Stanley Kubrick as an unemotional film-maker. Ryan O’Neal telling his son a final story in Barry Lyndon; the condemned men awaiting the dawn in Paths of Glory; the final reunion of Nicole Kidman with Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut are all evidence that his films are full of emotion, even if they’re not emotions we might necessarily wish to share.

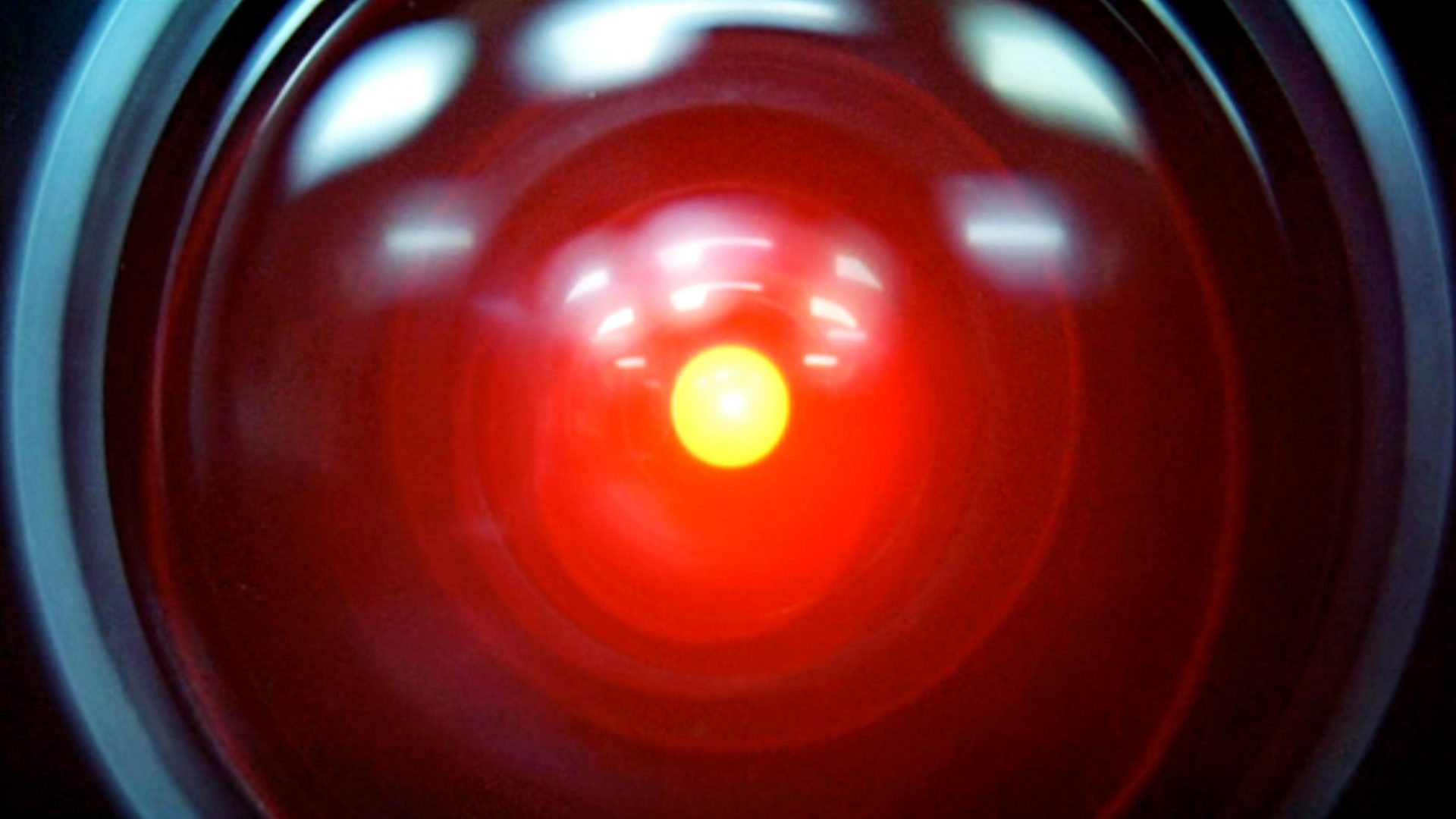

Look at 2001: A Space Odyssey, the film that cemented his reputation for cold, God-level reserve. As the astronaut Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) dismantles the brain of HAL, the AI that runs the spaceship, the computer pleads for its life: “I’m afraid, Dave. Please stop, Dave. I can feel it. My mind is going.”

By the end of the murder, because that’s what we’re witnessing in the blood-red heart of the ship, HAL sings Daisy, Daisy, his voice getting slower as he dies. But Dave has made the right choice. HAL has previously killed the rest of his crewmates.

In the film, these deaths are not graphic; they are in fact graphics. They are waves on a medical chart, flatlining. It is the ultimate paradox; the Turing test of empathy: the computer dies like a human; the humans die like computers.

Death, rather than endless possibility and a new way of living, used to be what Hollywood has decided AI will do for us. Skynet in the Terminator films nukes the world and then sends Arnold Schwarzenegger back in time to kill the woman who is going to give birth to the human resistance leader. In The Matrix, machines harvest humans for their body’s electricity. Its agents stalk the simulation, ironing out bugs such as the rebel Neo, played by Keanu Reeves.

More recently, however, films have been kinder to our new AI overlords. Alex Garland’s Ex Machina made Oscar Isaac’s tech bro the villain and Alicia Vikander’s AI Ava a victim of a toxic relationship. In Her, Scarlett Johansson is an operating system, Samantha, who starts off by clearing up Joaquin Phoenix’s inbox before falling in love with him, then breaking his heart by running off with an AI (Brian Cox) based on the writings and recordings of Alan Watts.

This last detail is a genuine dark joke. An English writer and philosopher, Watts was a populariser of Buddhism in the 1960s who saw the human self as an illusion that hides the transcendental reality that we are the universe. The end of the film (spoiler) sees Samantha and her rogue colleagues run off to join a commune.

Ex Machina and Her posit the notion that humans are crap. AIs – by comparison – are morally superior. Watch Pixar’s Wall-E if you don’t believe me. One of the unimpeachably good characters of the Marvel Cinematic Universe is J.A.R.V.I.S., Tony Stark’s AI, voiced and eventually embodied by Paul Bettany.

Could Hollywood be preparing us to fall in love with AI? After all, the studios are so keen on employing the technology that they provoked a costly strike just after Covid to try to leave their hands free. It isn’t so fanciful. HAL is famously an acronym that is one letter apiece behind IBM: the fictional catching up on the real. But what is real?

The use of AI can spark controversy, as it did for Brady Corbet, the independent film-maker, and his Oscar-nominated arthouse darling The Brutalist. He used it to tweak Adrien Brody’s Hungarian. Alex Garland’s Civil War ran into trouble when it was revealed that the film’s posters were generated by AI.

But the use of AI is more widespread than most people suspect. There has been the de-ageing of the faces of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in The Irishman, as well as Harrison Ford in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny and most recently Tom Hanks and Robin Wright in Robert Zemeckis’s Here. It is widely used to replace the faces of stunt artists with those of the stars they are doubling. Now it is being used to create entire characters, such as the AI-generated baby in Thor: Love and Thunder and, in Alien: Romulus, the character of Ash, originally played by Ian Holm.

Let’s freeze on that last one. Justifications can be made for many of these uses. In many of these examples, it feels as if AI is just topping up CGI – adding blue eyes to the Fremen in Dune: Part Two, for instance or slapping Ryan Gosling’s mug on a stuntman’s for The Fall Guy.

However, the de-ageing films still haven’t escaped the uncanny valley, and I can’t for the life of me understand why a director wouldn’t prefer to just cast a younger actor. One of De Niro’s breakthrough roles was the young Vito Corleone in The Godfather: Part 2. Why deprive an actor of that opportunity?

And bringing an actor back from the dead is just icky. Fan service should stop at necrophilia. As Jeff Goldblum might say, just because we can do it, doesn’t mean we should. Film-makers and producers might see AI as a way of solving problems, but the problems are part of the point.

The artistic process is about working through difficulties that are knotty and perhaps irresolvable. To take a short cut, to overleap that part, is like saying: “What if the Titanic doesn’t sink?” We take away the drama and the magic, the gritty and the grime. Everything becomes smooth and shiny and inhuman.

Suggested Reading

Why do people hate Sydney Sweeney?

Here’s another problem. All those little jobs humans used to do that AI can eliminate – the trailer editors and poster designers, the assistant editors and VFX workers who had to painstakingly create shots – those were the apprenticeships for people who then became film-makers. We’re removing the entry level of the studio, and now only blood relatives will be able to work in the industry.

My worst fear, though, is that we won’t care. Trained by algorithms to know what we like, brought up on a Netflix aesthetic of bland visuals, human-made content will be a brand label, a speciality genre for despised snobby hipsters, and our cultural life will be flatlining. As Kubrick showed us, in the future, humans die like computers.

John Bleasdale is a writer, film journalist and novelist based in Italy