“Morality does not have a chance with her. Good and evil are part of conventions to which she would not even think of bowing.”

The feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir wrote that of Brigitte Bardot in 1960 and it remained true until the death of the actor, activist, agitator and international icon at the age of 91 on December 28.

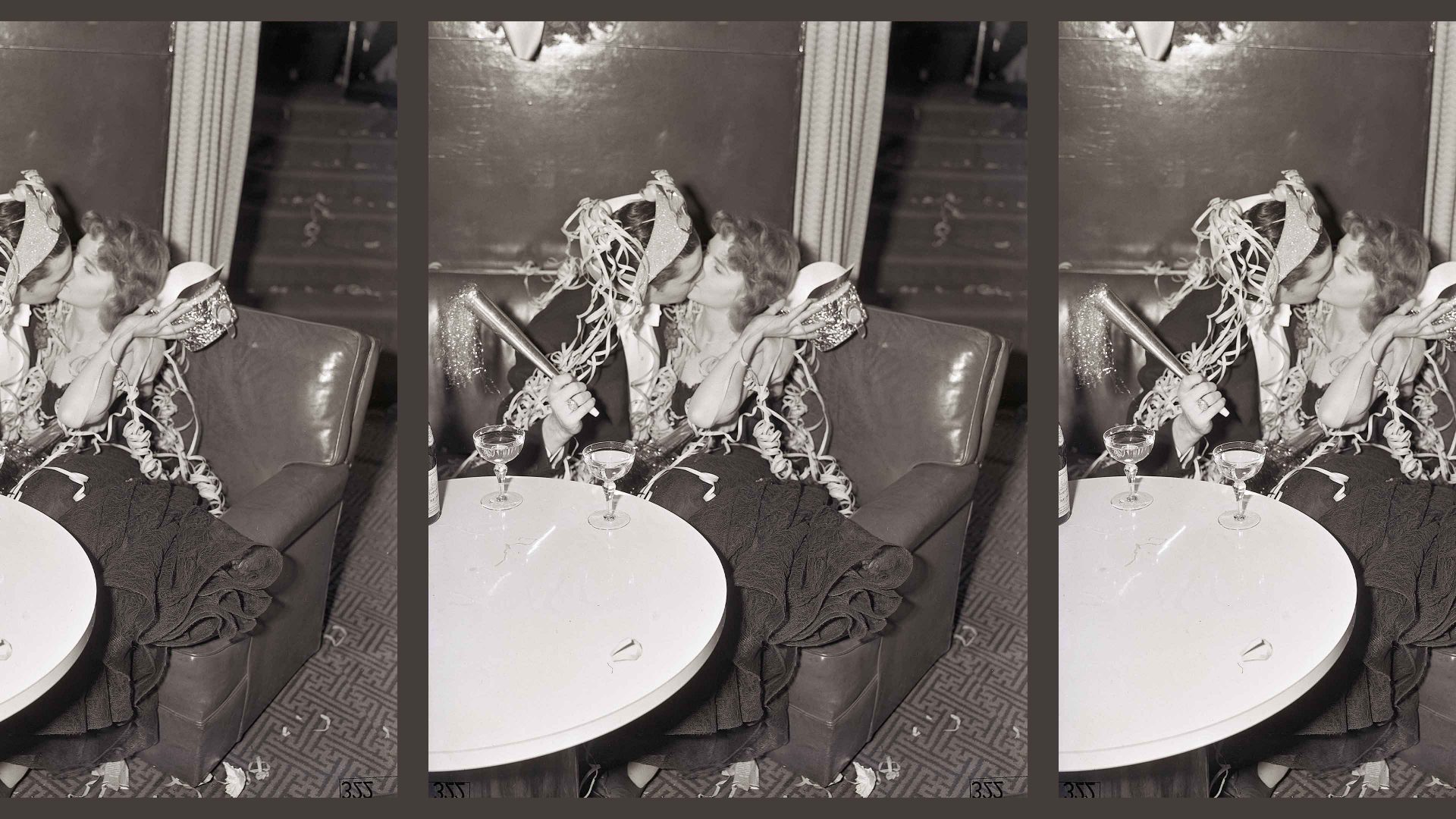

Bardot’s unabashed sexuality defined the era in which she rose to international recognition, but she also shaped the fetishisation of celebrity and another pervasive theme, that of casual racism disguised as concern about cultural erosion.

Bardot was born the daughter of a wealthy factory owner and an upper-middle-class mother. She was brought up in the kind of conservative family ripe for revolution. They would seek to contain her, educate her, restrain her and forbid her, she would stick her head in the oven until they gave in. And they always had to give in.

When considering her film career, two things stand out: one is how brief it was and two, how few films she made that have had any sticking power. Her first major hit was in 1956 with Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman . She would retire from acting a mere decade and a half later in 1973 with her last role in The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot.

In between, there are many fun roles and a surprising number of westerns, including one particularly international western in which she starred opposite Sean Connery in his only cowboy role. She didn’t succumb to his charms. She’d note: she was no Bond girl.

The only true masterpiece was Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris, in which she appeared in the opening scene lying in a bed, nude and inviting her husband to praise various parts of her body. Georges Delerue’s music gave the film heart and Bardot brought Godard’s intellectual asperity some flesh.

And yet despite these slim pickings on celluloid, her impact was vast. She had trained as a dancer and had caught the eye of Vadim who was to become her first husband, a relationship that would break down on the set of his debut film as a director and the one which would make his wife a star. It was in the publicity of the film that the director and his star began to create the character of BB.

Her previous career as a pretty girl in French and Italian comedies or opposite the likes of Kirk Douglas and Dirk Bogarde was swiftly forgotten and, with the pouty face of a child with the body of a woman, the sex kitten was born.

Suggested Reading

Renate Reinsve’s impossible journey

BB became the cool answer to the sex symbols of the 1950s. Instead of those buxom women with their manicures and furs, she was the wild child, barefoot and uncoiffed.

Of course, that wildness was no more authentic than Monroe’s dumb blonde schtick. They both fed into male fantasies as well as female aspiration. Wouldn’t it be good to be as wild as BB? She was the original dance-like-no-one-is-watching girl, the heartbreaker who’d love the bastard, but only for a while. She could be the muse but she’d break your sculpture and tear your canvas with her teeth if she felt like it.

In France, she was the fodder of the tabloids and not as beloved as she was in other parts of the world. The French perhaps saw her as a more recognisable type: the spoilt Parisian. They knew which arrondissement she grew up in, after all.

Nevertheless, her every move was followed, every affair scrutinised. There was unhappiness, instability and suicide attempts. And passion.

Bardot freely admitted that she was usually the first to start packing once the first bloom was off the rose of love. Her infidelity made for another power reversal that the 1960s had ushered in. She was the girl you couldn’t keep.

And neither did she want motherhood. When she fell pregnant, she was unable to get an abortion and was candid in her lack of maternal feelings, referring to her son as a tumour.

Serge Gainsbourg – another lover – would sing about “Initials BB” and she would sing along on the album of that title. He describes her as a chalice brimming with beauty dressed only in “… a perfumed air of Essence de Guerlain in her long hair.”

Together they would sing Je t’aime, a song Bardot had demanded Gainsbourg write her after she’d felt their assignation had not been up to snuff. As it turned out the recording/petting session created a version so sexy that her then husband demanded they withdraw the single. He re-recorded it with Jane Birkin to scandalous success, but the original would finally be released in the 1980s.

Having retired as an actor and entertainer at 40, Bardot devoted the rest of her life to animal welfare but this legacy was more than a little compromised by her tendency to rant about Muslims and “savages” so frequently that the prosecutor who successfully charged her with inciting racial hatred got to the point of complaining in open court that she was bored of having to deal with Bardot so often. She was a friend of both Marine Le Pen and her father Jean-Marie, and was married to his adviser Bernard d’Ormale until her death.

This feels like a sour note on which to end an obituary, but Brigitte Bardot was a woman who demanded to be taken all in all. She was never trying to please us. As far as she was concerned, we could please ourselves.

John Bleasdale’s new novel Connery, about the life of Sean Connery, will be published in February