When David Lynch died a year ago, the loss was greeted by the filmgoing community with an outpouring of tributes and love that would have been frankly astonishing at most points in Lynch’s film career. This was a man whose films had been treated with bafflement, if not outright derision upon their release. He’d been accused of shallow obfuscation, implicit racism, and outright misogyny. One critic said that Lynch’s movies left audiences baffled because he was baffled himself.

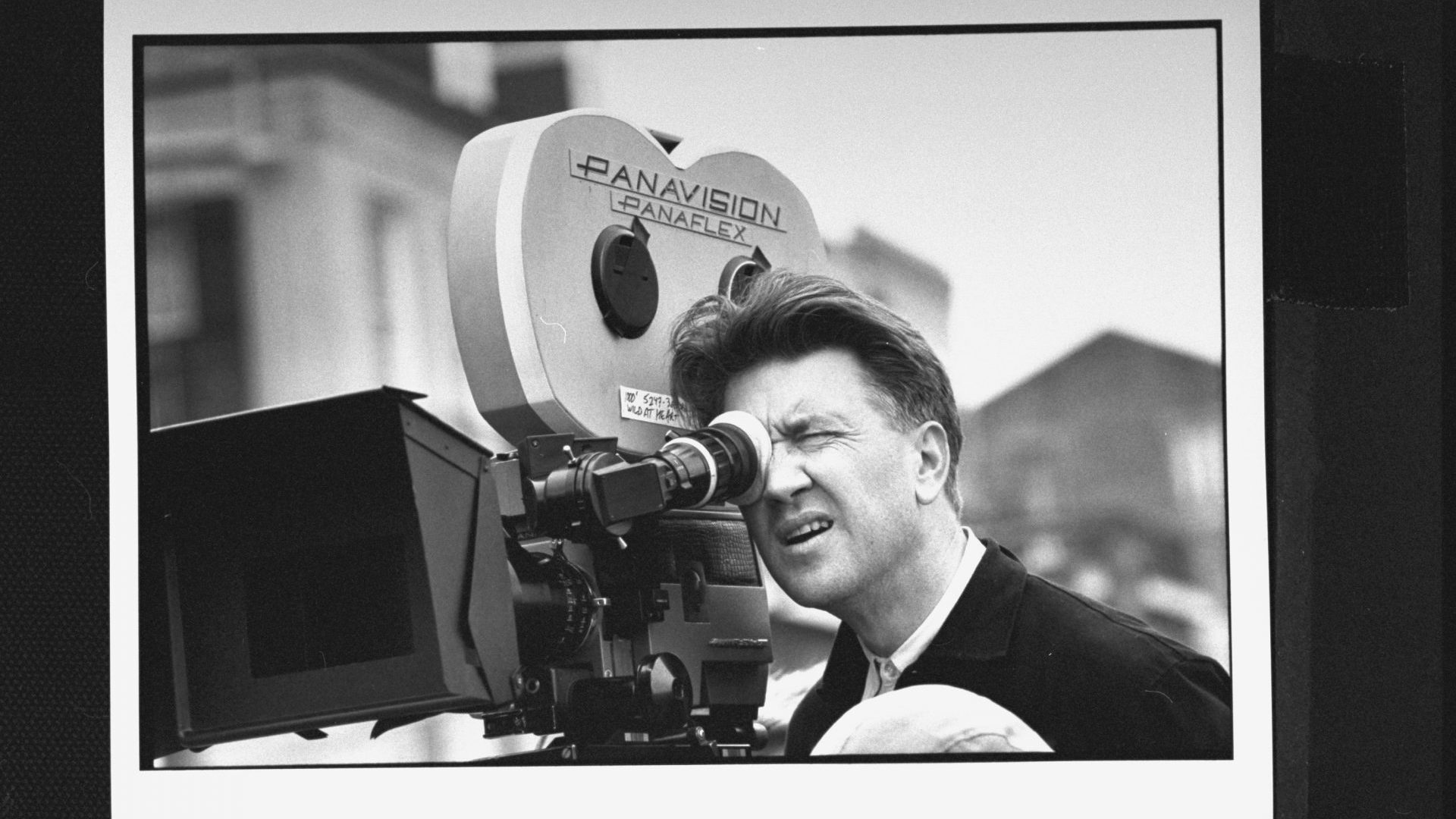

For every success, there seemed to be a flop. For The Elephant Man, there was Dune. Blue Velvet was a comeback; Wild at Heart felt wobbly. For Twin Peaks, there was Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Mulholland Drive and The Straight Story were celebrated; Lost Highway and Inland Empire less so.

Roger Ebert reacted so strongly against Blue Velvet, it sounded as if he’d been forced to witness a crime with the victim being Isabella Rossellini, sexually tormented and humiliated, and put on display. It was bizarre for a film critic who’d watched thousands of films to suddenly find himself unable to distinguish between performance and reality. Ebert and Siskel, by far the most prominent film critics in the US at the time, also gave Lost Highway two thumbs down which Lynch incorporated into the film’s publicity, writing “two more reasons to see Lost Highway” on the posters.

But time has been on Lynch’s side. Time and again, films which initially stumbled now seem to stride. Critical reevaluation means there’s nary a Lynch film that doesn’t have a champion declaring it to be the ur-Lynch film. I very much enjoyed the two Denis Villeneuve Dune films, but nothing in them has stuck in my head the way the prawn-like Navigator or Sting in a leather thong from Lynch’s critically benighted version have.

As well as the turn in critical fortunes, Lynch had extended his work, abandoning the cinema 19 years prior to his death. The documentaries made about his life, his autobiography Room to Dream (I highly recommend listening to the audiobook, which he partly reads), his early adoption of the internet including the daily weather reports he gave from his work desk and his almost miraculous and epic television show Twin Peaks: The Return meant that his reputation extended well beyond cinema, elevating him to the status of a cultural icon.

After his death, clips proliferated of Lynch refusing to expand on the meaning of his movies – “Eraserhead is my most spiritual film.” “Elaborate on that.” “No, I won’t.” – giving his weather reports, railing against watching Interstellar on smartphones and talking about Transcendental Meditation.

But there’s a tendency to sanctify the departed. I used the term “cuddlyfication” in reference to Martin Scorsese recently and it could just as easily be applied to David Lynch: Scorsese has those face brows, Lynch has his gelato quiff. The point is something is lost in the incense. Somehow, Lynch stopped being Lynchian and started being, you know, Lynchy.

Rewatching Lynch a year on, I kept going back to the darkness: the genuine nastiness of his films. Darkness is not cosmetic for Lynch, it’s the canvas.

And the earlier criticisms have validity. In fact liking Lynch is the weird response. It’s like liking your nightmares. David Foster Wallace noted how Quentin Tarantino focused on a man getting his ear cut off, and Lynch focused on the ear. But it’s still an ear cut off, with scissors we learn.

Suggested Reading

Death to the celebrity documentary

The deformed baby of Eraserhead is essentially murdered by Jack Nance’s Henry, a father who’d rather stab his offspring (again with scissors) than care for it. Baron Harkonnen of Dune is a pervert and sadist who murders his attendant by pulling his heart plug and bathing in his blood. You know, for kids. .

And Ebert had a point about Blue Velvet. During the making of the film, Rossellini had to demand that Lynch stop laughing during the scenes in which her character Dorothy was being sexually assaulted. In one of the darkest moments of humour ever committed to an American film, Jeffrey’s (Kyle Maclachlan) date with Sandy (Laura Dern) comes to an abrupt end when Dorothy emerges from the bushes, naked and covered in bruises on Sandy’s lawn. Then, in front of Sandy’s parents, she points at Jeffrey and declares, adoringly: “He put his disease in me.” Worst. Date. Ever.

The horror of Blue Velvet is not that evil men like Frank Booth, played with frenzied guile by Dennis Hopper, exist but that there’s a little Frank Booth in all men, including those in the audience.

Women are brutalised throughout Lynch’s films. In Wild at Heart, Laura Dern is sexually assaulted by the grizzly Bobby Peru – Willem Dafoe as Frank Booth but with negative 20 dental hygiene. In Lost Highway, Patricia Arquette will be murdered and sexually assaulted at gunpoint (in that order). Twin Peaks centres around the incestual rape and murder of a prom queen. It was on TV during the time slot when they used to show Dallas.

Black people rarely appear in Lynch’s world, except to be the help, or to get their brains bashed in like Bobby Ray Lemon (Ray Dandridge) at the beginning of Wild at Heart. The FBI, on the other hand get a clean bill of health, with Agent Dale Cooper (Maclachlan) bringing clear-eyed order and asexual decency to Twin Peaks and Lynch himself appearing as his superior, Gordon Cooper.

Suggested Reading

The weird and dangerous history of Hollywood snow

Lynch was unerringly honest in his films and that meant revealing the prejudices of a straight, white, middle-class American man. His fears were poverty (gotta light?), the non-white, the female (including childbirth) and modernity – all that crackling electricity, all those white picket fences harking back to MAGA-land.

His insight was in seeing that the things he celebrated were inextricably linked to his fears: the ants scrabbling under the emerald blades of the perfect lawn, the Frank in every Jeffrey. I am certainly NOT saying that Lynch is racist, sexist and homophobic – Dean Stockwell’s campy turn in Blue Velvet? – but I am saying that his nightmares were filigreed with prejudice.

Consciously, he hated homophobia; he was a vociferous champion of his actresses, campaigning for Laura Dern to get Oscar recognition by sitting on Hollywood Boulevard with a live cow and smoking cigarettes. His autobiography made it explicit that he deplored racism as evil.

But he knew that when the dark comes…