In the aftermath of Robert Redford’s death, a story about him was widely shared on social media. It was one Mike Nichols told about when Redford was auditioning for The Graduate (1967), reading for the part of Benjamin, which eventually made Dustin Hoffman a star.

Nichols explained that Redford didn’t really fit the role: no one would believe that Redford had the anxiety of a young man who had struck out with women. “Struck out?” Redford asked. “What do you mean?”

The very notion of being rejected as a sexual partner was simply not part of Redford’s lived experience. “He didn’t even understand the concept,” Nichols said. It was like asking a colourblind person to think of orange.

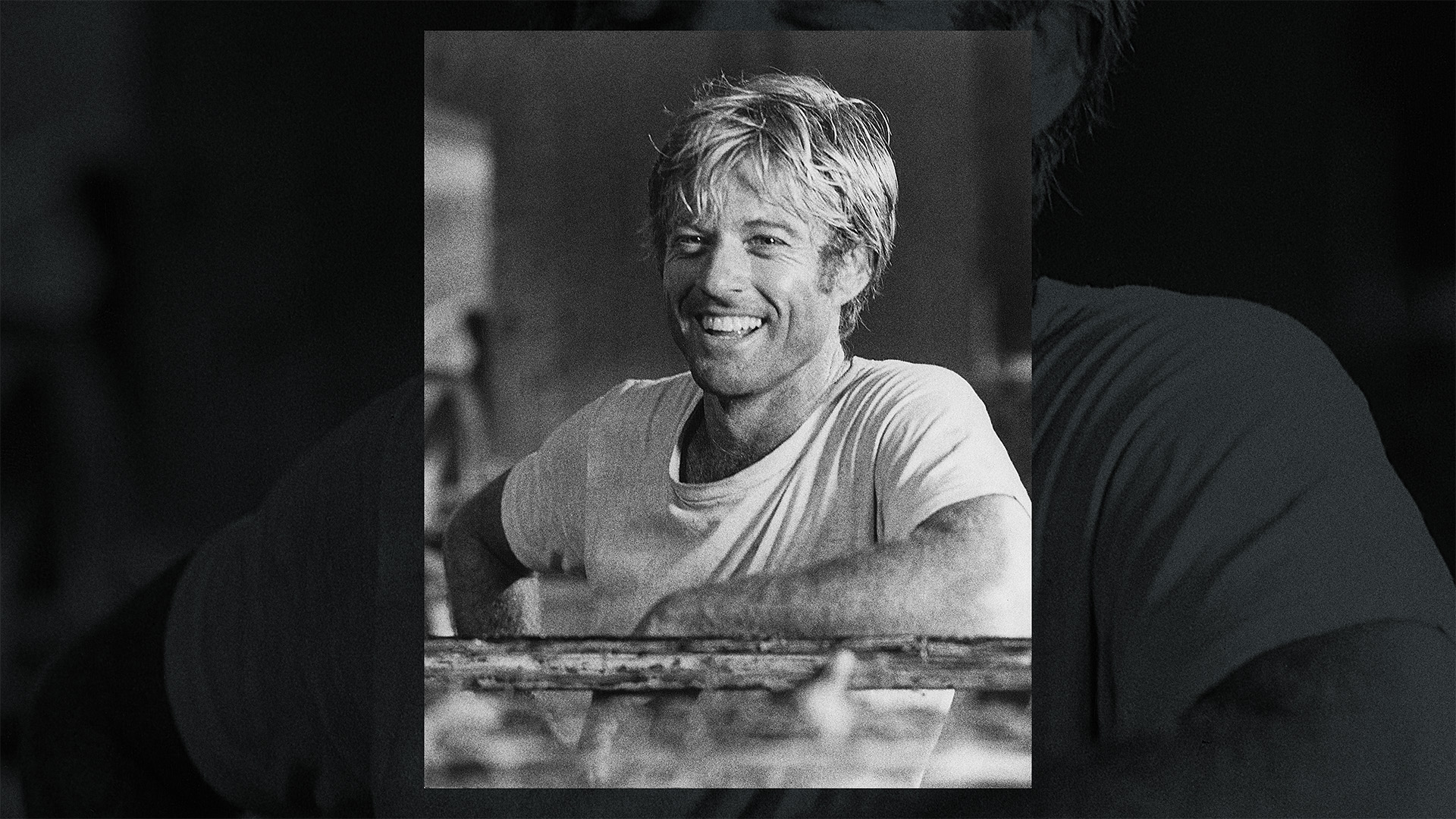

The story speaks to the almost holy beauty which Redford possessed. Another social media post after his death congratulated all men on just moving up one position in the global beauty index. Someone who hadn’t heard the news replied: “Was a really ugly baby just born?” Everyone else knew what was meant.

Obviously, there was so much more to Redford – the actor and director, the activist and founder of the Sundance Film Festival – and we’ll get to that. But in saying there was more, so much more, it’s also important to keep in mind this halo of drop-dead gorgeousness. Everything else was touched by that beauty; and Redford’s own subsequent anxiety, that perhaps it was all too easy.

You might go back to the old nutshell, men wanted to be him, women wanted to sleep with him, were it not for the fact that most men would have happily slept with him as well, regardless of sexuality.

Redford didn’t spend many years struggling. Born in 1936, and having goofed off through his youth, Redford broke into Broadway, television and film simultaneously in his mid-twenties. He debuted on Broadway in 1959 at the age of 24, on the big screen in 1960 in Tall Story and on the small screen from 1960, he played guest starring roles in some of the most popular TV shows being broadcast.

See his appearance on The Twilight Zone episode “Nothing in the Dark” where he plays a young man who turns out to be Death. It’s a beautifully played turn, which is all about how reassuring he is as a presence to the old woman, played by Gladys Cooper, who he has come to collect. It’s like Meet Joe Black (1998), but shorter and, you know, good.

The episode is essentially a two-hander and it is key to understanding Redford’s career to see him almost always appearing as part of an even-handed partnership. He was an actor who preferred to react.

He debuted on screen with Jane Fonda and appeared with her and Marlon Brando in The Chase (1966), but it was Barefoot in the Park (1967), in which he’d already appeared on Broadway, that he first began to get noticed. Have a newlywed couple ever looked more beautiful than Fonda and Redford in 1967? And the two of them sparring with Neil Simon’s waspish gag-a-minute dialogue proved irresistible.

Another partnership was at the core of his first major success two years later. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) was a transitional film. It took a classical Hollywood genre – the western – toothsome movie stars, a Burt Bacharach song and yet it put us on the side of the outlaws. This was no The Wild Bunch (released the same year) – as David Thomson put it, one smells of corpses, the other of cologne – but it gave the audience a fresh modern twist all the same.

Although Katherine Ross was nominally Redford’s love interest, it was the bromance between Paul Newman and Redford that stole the film. Newman was more verbal, wittier, had more personality, those eyes, my God, those eyes, but beside him Sundance could be the homoerotic straightman. Poised in the love triangle, no wonder Ross didn’t mind that raindrops were falling on her head.

Although the film was critically lambasted, it caught fire at the box office and Redford was now an established and bankable star. Famously choosy and hesitant, he picked projects that were fascinating and different, even if they didn’t always become hits. The adaptation of the James Salter novel Downhill Racer (1969) and the stylish heist thriller The Hot Rock (1972) are two such which have since gained cult popularity, especially the latter, which was all over my timeline when news broke of Redford’s death.

In Sydney Pollack’s Jeremiah Johnson (1972), Redford showed that he could go it alone: and by alone I mean truly alone. In the revisionist western, Redford plays the eponymous war veteran and mountain man who must survive in the wilderness and overcome grief and violence along the way, before coming to a form of understanding with the indigenous people around him.

Pollack proved simpatico and also directed The Way We Were (1973), another two-hander, this time opposite Barbra Streisand. It’s both a love story and a political dialogue between the politically active Streisand and her conservative with a small c lover.

The team of Newman and Redford got together once more for The Sting and reaped the rewards of more box office. In the year of release – 1974 – Redford had three entries in the top ten of highest grossing movies.

The Newman films were glossy, slightly empty entertainments (but as far as empty entertainments go, two of the best, to paraphrase Woody Allen on sex). From that Twilight Zone on, his seductiveness was a knowing part of his art. He could be a conman or cowboy, and you’d be taken in.

Look at his Jay Gatsby in Pollack’s The Great Gatsby (1974) and eat your heart out Leonardo di Caprio. He knew that he could be the all-American Boy, the sweetheart, the pin-up. He was the blonde-haired white American male, with all the advantages that bestowed. When in All the President’s Men (1976) playing journalist Bob Woodward opposite Dustin Hoffman, his old Graduate nemesis, it’s utterly credible when he admits to voting for Nixon.

But he was also willing to use that privilege, that appearance to investigate and criticise America. With a film like 1972’s The Candidate, he investigated the corruption of an idealistic and charismatic politician in what looked like it could even be a dress rehearsal for a run for office. But the film itself is an argument for the almost inevitable corruption that the system has built into it.

Thrillers such as Three Days of the Condor (1975), likewise reflected a pessimism and paranoia about the political system rooted in the immediate aftermath of Watergate. These were not bromides. His heroes were often doomed to failure or worse, but this only made the challenge and the necessity for activism more necessary.

Redford’s real-life activism came with his conservationism and his support for gay rights, as well as his lasting contribution to American independent cinema, a contribution it would be difficult to overstate. Having settled in Utah with his wife and fellow activist Lola Van Wagnen, who he’d married in 1958 and with whom he had four children, the couple bought land which he named Sundance.

With the money he earned from his films, he created the Sundance Film Festival in 1978 and then extended it into an institute to help promote filmmakers. Steven Soderbergh and Quentin Tarantino were among the many who would benefit from the launching pad and visibility Sundance provided.

As a film director himself, as was consistent with his career, Redford started at the top, winning an Oscar for his debut film Ordinary People in 1980. Having only been nominated once as an actor (for The Sting of all things), he took home the trophy on his first swing against David Lynch and Martin Scorsese at the height of their powers.

His career from the 1980s on would see more sporadic success both in front of and behind the camera. Out of Africa showed he hadn’t lost his romantic lead chops, and Quiz Show demonstrated his keen awareness of American venality had lost none of its quiet anger.

These are the days of the dying giants. I’m old enough to remember when Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn still walked the Earth and now they seem to be as distant to us as the Gods of the Greeks. Icons like Paul Newman, Sean Connery and now Robert Redford have gone and with them an era is closing. It is the end of a pre-Netflix, pre-social media age and it’s hard not to get misty-eyed for what we’re losing in the process, as much as Timothée Chalamet might console you.

A perfect summation of Redford came with the late-career highlight of JC Chandor’s All Is Lost (2013), in which he plays a nameless sailor who finds his ship sinking in the middle of the ocean. It is a story of resilience and perseverance. Redford barely says a word throughout, has no backstory, no apparent inner life and looks his years.

And yet it might well be the performance of his career. The final proof – if it was needed – that he could do without a scene partner. It is utterly compelling. When he squints at a gathering storm on the horizon, “Our Man,” as he’s named in the credits, goes below deck and shaves. If he’s going out, he’s going to look as good as he possibly can. When death came, it was in his sleep. It was a generous way to go and suited what Death (played by Redford in The Twilight Zone) tells his next recipient all those years ago: “What you feared would come like an explosion was like a whisper.”