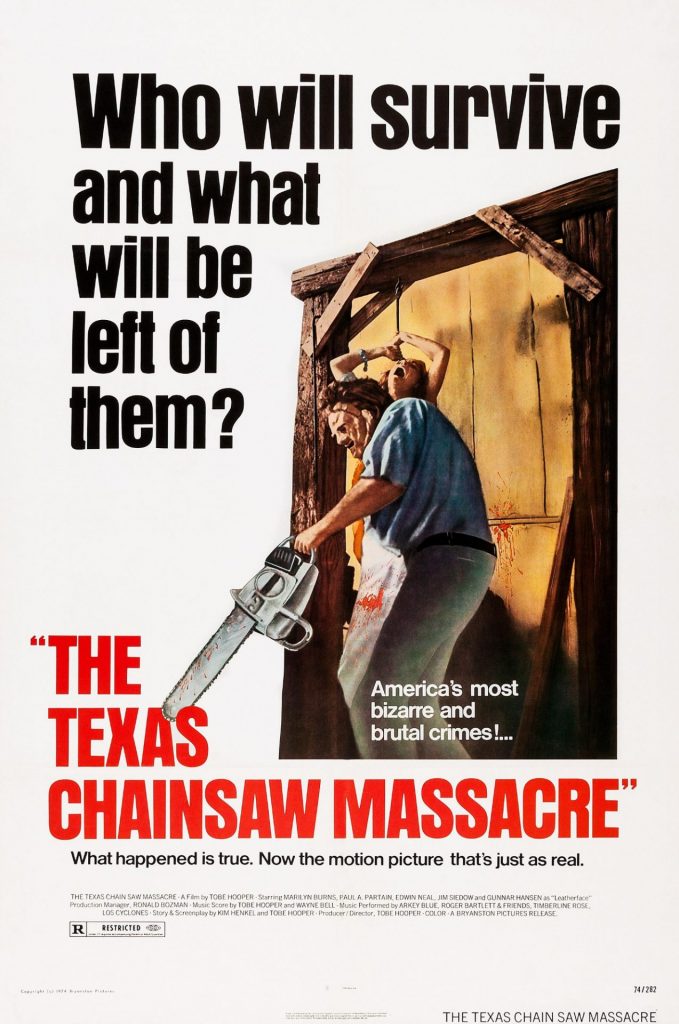

Superlatives are the dribble left on the pillow when journalism is sleeping one off, but I stand by the statement that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is the most terrifying film ever made. Now, a new documentary, Chain Reactions, by Alexandre O Philippe confirms what I already know.

Stephen King, Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, Patton Oswalt, Karyn Kusama and Takashi Miike are also in my corner. Since the documentary consists of these film-makers, a critic, a writer and a comedian recounting their own personal relationship to the film, I feel utterly justified in giving you mine.

It was summer, 1983. Cumbria. I live in the countryside. It’s not Wordsworth’s daffodils. It’s more cowpats and scramble bikes: the sort of place farmers hang dead crows on barbed wire fences as a warning to others from the murder.

Me and my next-door neighbour Dave – I was 11, so excuse the grammar – went down to the Shell garage and rented the film. I didn’t have a VCR yet so we went back to Dave’s house (his parents were both at work) and we watched the film. Or at least we began to watch the film. It freaked us out, but neither of us would willingly turn it off and admit we were scared.

We watched the teenagers in the Scooby-Doo van pick up the hitchhiker and then get rid of him, then stop for petrol. That annoyed us. We saw an America that we recognised from The Waltons and The Dukes of Hazzard, rustic, dusty roads and outlaw-ish. We felt that heat even as Kirk goes into the house and we know something is going wrong. Even though it’s broad daylight.

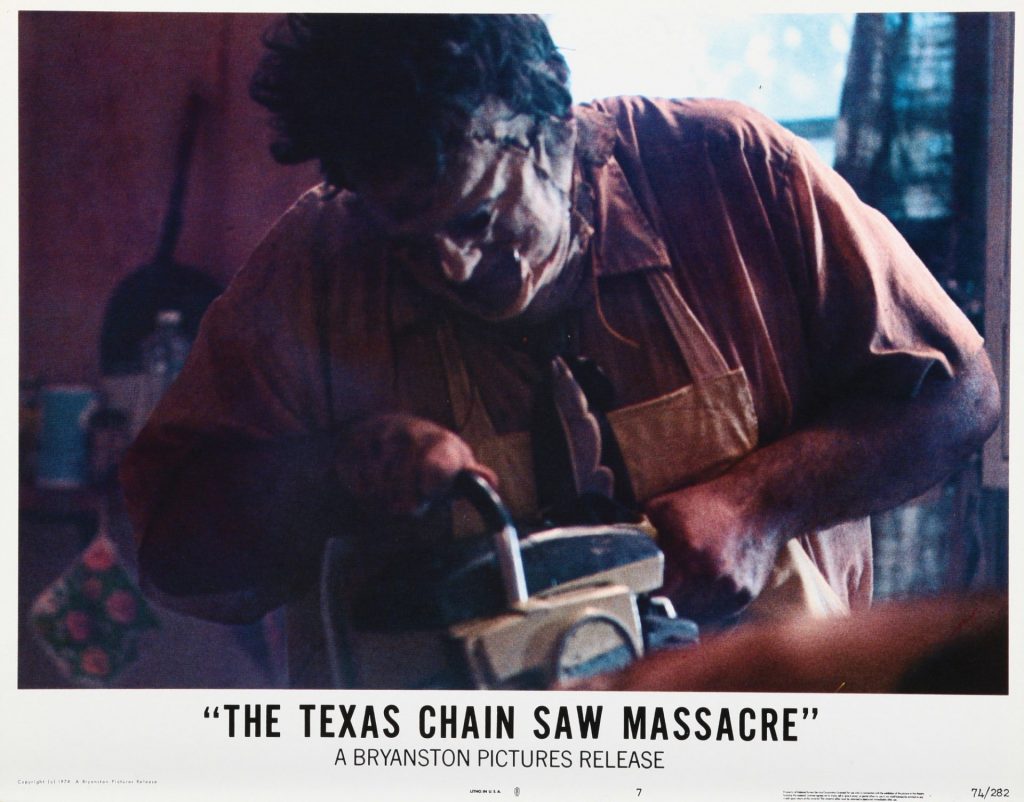

That moment – when Kirk trips or slides and a giant man wearing an apron and a mask and wielding a sledgehammer – has stuck with me for ever. The hammer blow. Kirk’s spasming foot. It’s a moment of terror that was traumatising.

I don’t know how far we got after that, but we had to break because Dave’s mum was coming back for lunch and I had to go home. We’d watch the rest in the afternoon and see how the teenage girl escapes and kills the giant madman with the chainsaw. Except when I went back, Dave had taken the tape back to the garage.

Was I secretly glad? Did I really need to see the death of the giant to put my fears to rest? What other tortures did I miss? Wasn’t I better off without them? Didn’t I really want to unsee what I’d already seen?

But the video was back in the shop, and soon James Ferman, head of the British Board of Film Classification, would ban it as part of the attack on video nasties, remarkably saying: “It’s all right for you middle-class cineastes to see this film, but what would happen if a factory worker in Manchester happened to see it?” He could’ve replaced “factory worker in Manchester” with “11-year-old from Cumbria.”

The film would be denied certification until Ferman retired in the 1990s and even today, when horror films of the seventies such as Halloween have had their certificates downgraded from “X” to 15, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remains an 18. Further proof of how deranged director and co-writer Tobe Hooper was that he actually thought he was going to get PG if he kept the blood down to a minimum.

Fast forward 20 years later. It’s 1999, I’m in Italy: and a friend has given me the DVD of the film. I’m working in the evening, teaching English courses, so I decide to watch it one morning before lunch. No problem, surely, not now I was an ardent horror fan and “middle-class cineaste,” as Ferman said.

Fuck me, it was scary.

I couldn’t sit still and watch it. Almost from the get-go, I had to get up and walk around.

Kirk’s death was just as traumatic as it had been initially. And then Pam’s naked back and the hook! Franklin’s evisceration in the wheelchair. The moment you feel Sally might have got away, only to find the cook at the gas station is actually one of the family.

And then to find out that the family itself is not just this single entity of evil, but has a complex, nuanced, layered dynamic. The hitchhiker yells at the cook: “He’s just a cook” because he won’t kill anyone.

The cook admits he doesn’t like the killing, but he slavers as he beats Sally with a broom handle even as he consoles her. “It’s going to be alright, you just be quiet now.” WHACK WHACK WHACK!

And Leatherface, weirdly, is both terrifying and a mindless child. An 11-year-old.

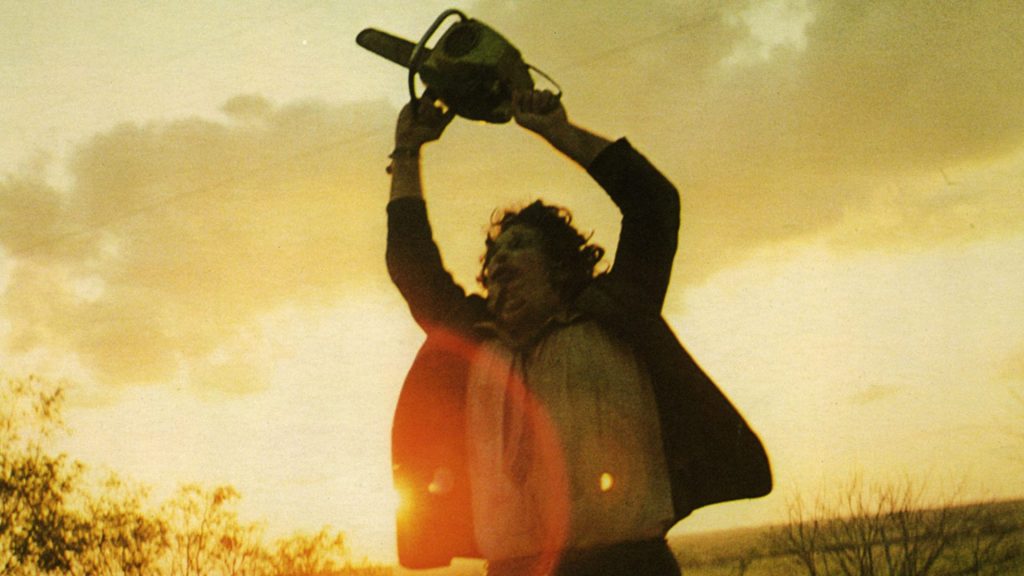

As Ferman rightly pointed out, you can’t censor The Texas Chainsaw Massacre because the sadism, the terror, runs all the way through it from the initial solar flares to Leatherface’s demented chainsaw pirouette to greet the dawn at the end. Oh, and another thing, 11-year-old me, the monster doesn’t die at the end.

I’ve rewatched the film several times since then. OK, once. It stands out as the best horror film ever made, bar none. All the others have been compromised by wonky special effects (The Exorcist) or over sequelification (Halloween, The Nightmare on Elm Street, the Friday the 13th films).

Of course, Chainsaw has had its remakes and its sequels, but, like Jaws, the 1974 original exists in an entirely different category of being to the cash-ins. As Rob Savage, the director of Host and The Bogeyman, once told me: “It feels like this was a film found in a rusty bath in a farmhouse somewhere.”

It has the tone of a snuff movie. The fact that none of the actors were famous before or later means that, like Cannibal Holocaust and The Blair Witch Project, the viewer is left with an uneasy feeling that they’re not so much watching a movie as witnessing a series of crimes.

Horror is no longer the video nasty scapegoat it once was. As Clark Collis’s recent book Conjuring and Screaming convincingly asserts, it has had the staying power of a zombie army and can be found everywhere now from the multiplexes and popular TV shows to the art house cinemas.

There’s been a gentrification of horror with films like Hereditary and Get Out giving us an intellectual bang for our scary buck. In Chain Reactions, Karyn Kusama gives the most intellectual reaction to what she calls “an American masterpiece,” arguing for the film as a political statement that is prescient in predicting the violent cannibalism of the Trumpian hordes.

As Vicky Pollard might say: “Yeah, but no…”

The visceral feeling of the film is paramount to me and the deconstruction of the film feels like someone asking my shoe size while I’m hanging on a meathook. The film deconstructs us; we don’t deconstruct it. And it does it with a chainsaw.

In a final attempt to allay my fears, exorcise them, kill the monster, I went to Texas in 2022. I was there to research a book on Terrence Malick, who – lest we forget – made his debut with Badlands, a film about a murderous crime spree. With some downtime, I decided to visit the locations of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. I thought doing so and seeing them in context would help.

The house had been moved 60 miles from its original location and was now a bar and restaurant, and full of regulars drinking mid-afternoon cold ones amid the movie memorabilia, including a life-sized Leatherface. The lady at the bar ushered me into the famous hall where Kirk had been killed, and up to the attic where there was a dummy of Grandpa.

It was all spruced up: tasteful and tacky at the same time. It had nothing of the stink, the feathers, the bones, the danger of the film. Obviously. And yet…

Suggested Reading

Will HAL kill Hollywood?

I posed for a silly photograph outside, collaring a nonplussed local to be my DP. I went on to the BBQ and gas station which was still operating, according to the Austin-based tourist site I was using.

This was on the road to Bastrop, a small town. The road was deserted and the fields stretched away. Texas around Austin is fairly flat. On the radio, there was a preacher demanding money and having a go at Catholics.

Whereas the house had been in the middle of a community, with a car park provided, the gas station stood on its own and looked identical, as in run down. There was no one there, but a bench outside with a chainsaw demonstrated that they were in on why people might be dropping by.

They still did barbecue and I could hear the sound of sizzling meat from somewhere inside or to the back of the place. I thought I could get some meat before I went to the graveyard where the film starts.

But the door was closed. I wasn’t going to try to see if it was locked. There’s no way I’m going to do a Kirk. I walked around the side, and the noise of sizzling and someone chuckling could be heard.

I drove away quickly as the preacher on the radio railed at the cannibalistic practices of Catholics. I skipped the graveyard. The monster is still alive. Pirouetting in the sun.

Chain Reactions is available to stream, via Google Play, YouTube and AppleTV+

John Bleasdale is a writer, film journalist and novelist