It’s one of those moments that recurs periodically at the Cannes Film Festival. You watch a film that exposes the inequalities of the world, the injustices, or the instances of oppression and unfairness. You witness the marginalised and those left behind in films by the Dardenne brothers and Ken Loach, or the extravagantly awful rich being pilloried in Ruben Östlund’s The Square or Triangle of Sadness (both of which won the Palme d’Or). Then you step out on to the Croisette, next to the casino, opposite the stores of Prada and Dolce & Gabbana.

The cognitive dissonance is to be savoured or it will drive you mad. Critics from across the world sit in darkened rooms watching tales of despair and desperation while outside super yachts sleep in the harbour, rocking gently on the Mediterranean.

At last month’s festival, the disparity between the reality of the world and unreality of the cinema was stark – and sometimes those two states switched places. War in Ukraine continues and several films devoted to the conflict playing at the festival – all from the Ukrainian perspective. There was once more no Russian pavilion promoting the country’s cinematic wares. The director of the festival, Thierry Frémaux, was even moved to introduce the very Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov as “no longer a Russian director” when introducing his film The Disappearance of Josef Mengele.

When it comes to the ongoing conflict in Gaza, the official stance of the festival has been much more muted and both sides-y. There was an Israeli pavilion and an Israeli film, Yes! by Nadav Lapid. But at the beginning of the festival, a letter was published with hundreds of signatories from the world of film condemning Israel’s ongoing killing of the population of Gaza. And two very different films set amid the unfolding catastrophe were shown.

From the stage of the opening ceremony, tribute was paid to Fatima Hassouna, the Palestinian photographer whose life is the subject of Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk – and who was killed in April this year. She should have been here for the film’s premiere. Instead, along with six members of her family, she was killed in the house where she slept by an Israeli air strike. No contrast could be more stark.

More of that in a moment. The other Gaza film at Cannes, Once Upon a Time in Gaza, bases its resistance in its very normality. Shot in Jordan by the Nasser brothers, Arab and Tarzan, it is a lo-fi crime movie with a slow-burn pace and a nice line in meta-fiction as a man desperate to escape Gaza and a life of semi-criminality finds himself picked off the street to star in a Hamas-inspired TV show called “The Rebel.” It owes more to Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher trilogy than to the Sergio Leone or Quentin Tarantino films the title alludes to.

But it’s punctuated by explosions as drones and missiles strike the city from Israel. “Making a film is resistance,” the hero is told, and although there’s an irony to the point – after all it’s a Hamas representative who is saying this – it’s also true. The normality of a crime film is a stubborn refusal to have artistic expression always react to the actions of the oppressor.

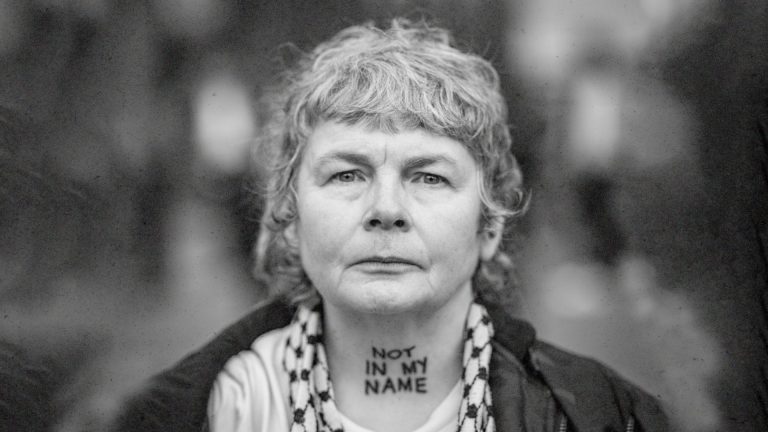

Suggested Reading

Misan Harriman: A lens on a world in protest

The Nasser brothers aspire to a genre of film-making which will allow their work to escape the spiral of violence even as it explores it. It aspires to a certain slickness, which contrasts with the rawness of Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk. The title comes from Fatima’s uncorrected English as she describes what it feels like to step into the streets of Gaza.

The film is basically a series of video calls between Sepideh and Fatima, occasionally broken by a news report or a political speech which gives context – although this in itself is not given without an obvious bias. The Iranian film-maker and the Palestinian photographer bond over the months despite the fact that their lives are completely different.

Sepideh, like us, lives in a privileged space where bombs don’t fall. She travels freely to film festivals. She has a nice apartment and a cat that demands her attention, and as much as she sympathises with Fatima, she can’t help sounding a bit impatient when the connection on the call is interrupted. We see her face reflected on the screen.

Fatima on the other hand is a young 24-year-old photographer who is moving from apartment to apartment and might be calling from a bomb shelter. Her belongings can be gathered in a handful of shopping bags. She has a radiant smile and family members who pop into view to wave.

Rather than being furious or despairing, she reassures Sepideh constantly that she’s OK. At one point, Fatima spends half the phone call reassuring Sepideh not only that she’s OK but that she values these connections. “But there’s nothing I can do for you,” Sepideh says. “I can’t send you anything.” “But you’re here with me,” replies Fatima, and delivers another of her warm, generous smiles.

And in between all of this are the photographs which Fatima takes. Images of devastation which we see anew through Fatima’s eyes. There’s a sense of immunity that is given to people who are looked at – looking is an expression of care, after all we “look” after people.

When Fatima doesn’t answer her phone, it feels like an awful moment. But it gets worse. In the final conversation, she is told that the film has been accepted for the Cannes Film Festival and arrangements are being made for her to leave Gaza and attend the festival. She is delighted, but also determined to return. “My family and life are here,” she says.

For all our looking, for all our bearing witness, the Israeli bomb still killed her and her family; and no words feel adequate in the face of that.

John Bleasdale is a writer, film journalist and novelist based in Italy