I refer you to The Sopranos, Season 3; episode 12: Amour Fou. Tony Soprano’s jilted, obsessive ex Gloria Trillo (Annabella Sciorra) is warned off by one of his henchmen with a gun and the deadliest of deadlines: “And here’s the point to remember,” Pat Parisi tells her, “my face will be the last you see, not Tony’s. And it won’t be cinematic.”

That last remark is the sort that elevates the HBO show to its rightful position as the most finely attuned description of the fantasyland that we live in via our cultural imaginings. Even our own violent deaths can be fantasised about, as Gloria does, as somehow glorious and legendary: “cinematic.”

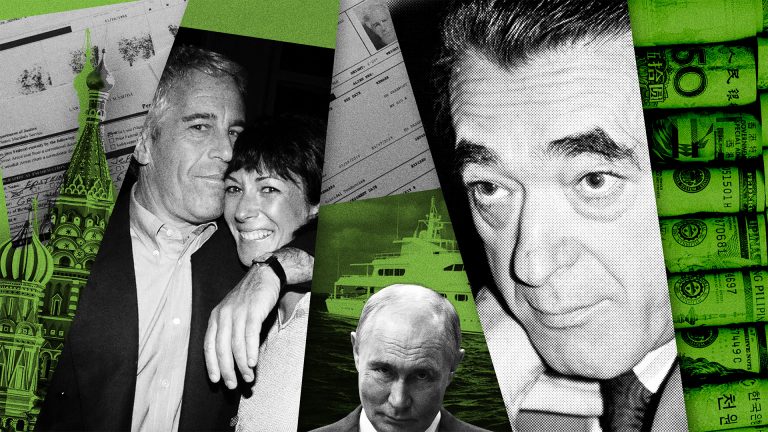

The recent release of photographs, emails, testimony and video from the Jeffrey Epstein files have revealed that evil looks like many things, but it rarely looks cool. “The banality of evil”, that term coined by historian Hannah Arendt when she was covering the Adolf Eichmann trial, has become a cliché, but it’s something that cinema struggles to portray. Austrian director Michael Haneke got close in films like Funny Games (1997) and The White Ribbon (2009); and The Zone of Interest (2023) strived but couldn’t help put an arty 7K gloss over the functioning of the household of the commandant of Auschwitz.

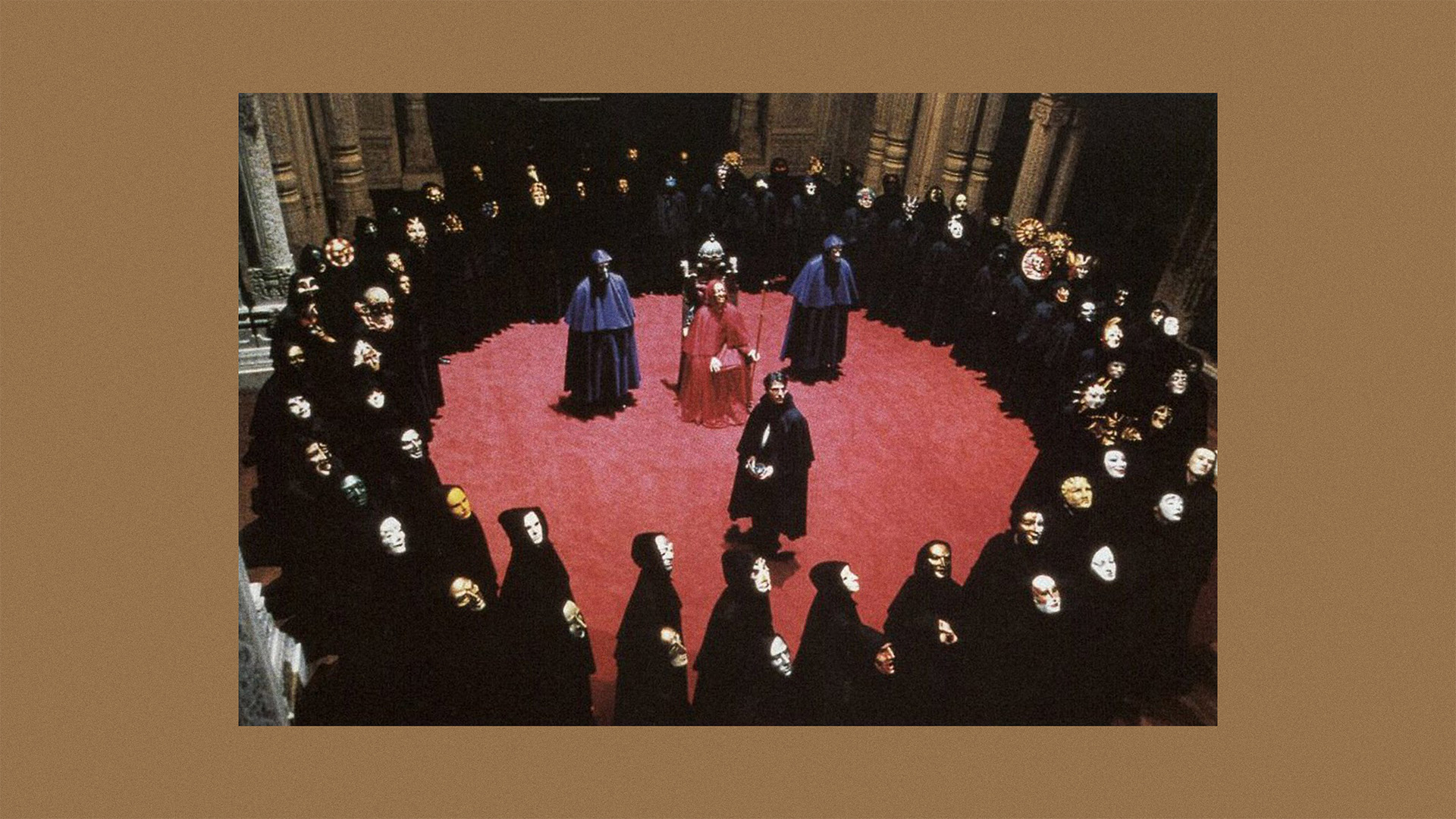

The closest parallel to the kind of high society sex trafficking of Epstein and his confederates comes in Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 film Eyes Wide Shut. Google the film and you will find that there are many who believe that Kubrick, along with faking the moon landings, was killed because his last film so accurately portrayed the Illuminati-like secret society that gives people like Dan Brown a stiffy.

You will see theories about a screening of the film for Warner Bros executives in which Kubrick could be heard screaming. Or an interpretation of the final shots of the film, where you see two older men escort Bill and Alice Harford’s (played by Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman) daughter away as a sacrifice. In reality, it’s more likely that they were extras corralling the young actress away from the action and out of shot, but knock yourselves out on YouTube.

Interestingly enough, one of the victims of the conspiracy mindset might well have been Stanley Kubrick himself. In his memoir, Eyes Wide Open, Kubrick’s co-screenwriter Frederic Raphael sent Kubrick a backstory for the elite club which has organised the orgy that is the centerpiece of the film.

Raphael describes a group – “neither a sect or a cult” – called The Free, who are free from love, democracy, correctness and publicity. Their parties use prostitutes and later female members are admitted. The cardinal rule is not to reveal the existence of The Free to The Slaves – everyone else. Plumbers are members who staunch any leaks with money and/or violence. Concealment was paramount, Raphael writes, but “the fear of exposure enhanced enjoyment. Life was a game not a morality.”

On receiving the document, Kubrick phoned Raphael, urgently asking: “Where did you get this stuff? This is classified material… Did you hack into some FBI computer by chance or what?” Raphael bemusedly assured Kubrick he’d made the whole thing up.

Kubrick still couldn’t quite believe it wasn’t real, quizzing his writer on whether he had based it on something factual, but Raphael had made it all up out of whole cloth. “How do you do that?” Kubrick asked, incredulous.

We all like conspiracy theories. They provide us with an almost metaphysical assurance that someone somewhere has a plan. A small cabal is directing us, even if it’s for nefarious ends. If God is dead, at least leave us the devil. Conspiracy theories are literally part of the occult, as in the original meaning of the word: the hidden.

There are, of course, actual conspiracies that are right out there in the open. When we are sold products and services for far more than they are worth; when we are paid less for more work; when companies and individuals refuse to pay taxes which contribute to infrastructure and benefits they themselves use in the creation of their own wealth; when human rights are compromised or dispensed with entirely for the interests of small groups to pursue their own imperialistic goals – these are just the Way Things Are Done.

We are told that the Market decides, or the Economy dictates and we don’t even question that language. We hear about shareholders and CEOs and their decisions trumping anything democracy with a vanishingly small “d” has to say.

The media, meanwhile, is being conglomerated, eviscerated, enshittified. At the start of February, The Washington Post fired a third of its work force, owned by Amazon founder and the third richest person in the world, Jeff Bezos. The man made his money selling books and The Washington Post no longer has a books section.

Far from revealing anything about power, conspiracy theories are the distraction. As Thomas Pynchon wrote: “You get them asking the wrong questions, you don’t have to care about them getting the right answers.” Look over there at the Deep State, the Illuminati, or whatever rebranding of the Elders of Zion we’re Groking about today and you won’t just miss the very nature of the world you live in, you’ll assist in its survival. You’ll become complicit in channeling off dissent, leaching away at the very possibility of critical thought.

Jeffrey Epstein existed in the context of the Totalitarian Rich (my coinage, you’re welcome), a class of one-percenters who want everything and exert extraordinary power, bending the time-space of civil society and democracy to get it. When Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) confronts the monstrous Noah Cross (John Huston) in Roman Polanski’s portrait of absolute corruption, Chinatown, he asks how much the old man is worth, $10 million? More? “How much better can you eat? What can you buy that you can’t already afford?”

Cross replies: “The future, Mr Gits,” and only at the end of the film will we discover how obscenely literal this desire is.

The obscenely literal takes us back to Epstein and his ilk.

In Eyes Wide Shut, the conspiracy is cinematic. The Plumbers appear in the film as a familiar conspiracy trope: the men in black. The secret party is talked about in hushed tones and takes place in a palatial country house with a papal MC, masked attendees and music of arty beauty, provided by Kubrick’s daughter Jocelyn Pook. The password is “Fidelio”, the name of Beethoven’s only opera.

When Business Insider identified Epstein’s playlist on Spotify, they found Van Halen’s Hot for Teacher and Eric Clapton’s Before You Accuse Me as well as a Louis CK stand-up routine. For all Noam Chomsky and Steve Bannon talk up Epstein’s intellectual heft, his emails read like bum texts.

Suggested Reading

The expensive boredom of Melania

The porny kitsch that filled Epstein’s Miami property compares poorly with the movie’s country house setting, or Zeigler’s (Sydney Pollack) game room with the red felt of his billiard table echoing the red palette of the orgy house. The orgy itself is tastefully shot sex. This is not Sean “Diddy” Combs’ ick, his baby lotions and spiked booze.

Kubrick’s sex looks consensual, professional even. Acceptably kinky. Everyone, crucially, seems to be an adult, except for an underaged girl in the costume shop, who is weirdly played for laughs.

In the posthumous collection of her writings Gravity and Grace, French philosopher Simone Weil nailed the difference between Eyes Wide Shut and Jeffrey Epstein long before either were born: “Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.”

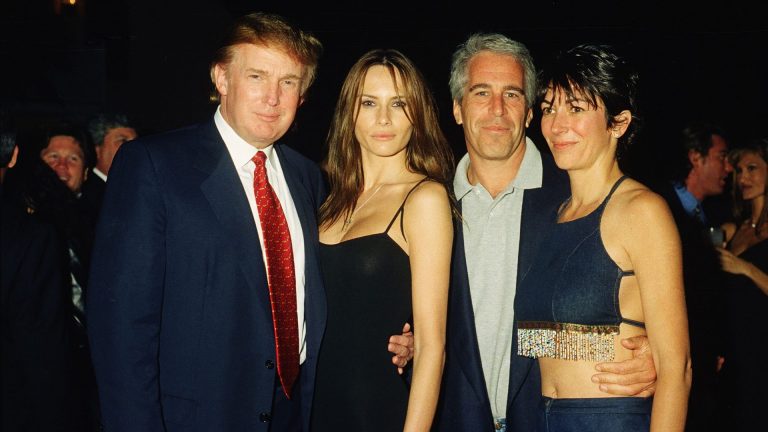

Francis Underwood in House of Cards is “romantic and varied”; Kevin Spacey IRL is “gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.” Tony Soprano and Walter White are varied and complex: Elon Musk, Donald Trump, Jeffrey Epstein, Peter Mandelson, Ghislaine Maxwell and Prince Andrew (let’s not let Buckingham Palace off the hook by using the debranded name they now want us to call him) are just a shower of shits. Bad people might be able to create works of art – the pop music of Michael Jackson, the films of Roman Polanski and Woody Allen – but their evil remains “gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.”

Look at any of those photos of Prince Andrew, the flash reddening the eyeballs. Look at the faces of the people surrounding POTUS, breathing in the KFC-flavoured cloud of nothingness. Read the joyless brainfarts of the South African entrepreneur who was mistaken for a genius until he opened his mouth.

Then there are the victims. Women like Virginia Giuffre, whose lives have been destroyed and who number in the hundreds. We have failed them. And we continue to fail them. The same newspapers printing editorials on the evil of Epstein have been complicit in minimising crimes against women and girls.

And the electorate? Trump won the first election after the Hollywood Access tape in which he openly confessed about sexually assaulting women, and his second election after a judge declared that E Jean Carroll’s allegation of rape was “substantially true.” We use phrases like “Lolita Express” – another Kubrick film – and we fantasise that Epstein might not actually have died, as if Epstein was a latter-day Elvis, another man who “liked them young.”

The New York Times greeted the November tranche of Epstein files with an opinion piece titled: “Epstein Emails Reveal a Lost New York.” Like they were the pages of a lost Edith Wharton novel.

We have to stop this. Epstein wasn’t Victor Ziegler from Eyes Wide Shut and what he did wasn’t organise elaborate Venetian-themed orgies. He was a rapist, pedophile and sex trafficker, and he wasn’t alone. He wasn’t fascinating. He doesn’t deserve a Netflix documentary. His death when it came in his New York prison cell, as Pat Parisi might say: “was not cinematic.”

But rather than linger on this man-shaped void, what about the second part of Simone Weil’s aphorism: “Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating.” Somehow, we have to find a way of making “real good” cinematic.

John Bleasdale’s novel Connery, about the life of Sean Connery, is published by Plumeria on February 23