There’s a moment in Federico Fellini’s masterpiece 8½ when Marcello Mastroianni, a film director with a creative block, is gifted the vision of Claudia Cardinale. She flutters into the scene like a ballerina or a butterfly, dressed as a nurse as he tilts the sunglasses down better to appreciate the vision.

The music drops out, she smiles at him and there is a silence of cinematic transcendence. She is the most beautiful girl in the world and she is kind, and she is generous, and she is smiling at you. And the world stands still. And then it’s gone.

It is the tragedy of beautiful women to be judged and described by the effect they have on men. As John Berger once famously wrote: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves.”

I’d argue there are women in cinema who look back: who challenge the gaze and make us lower our eyes. They become something beyond the male gaze. They have some ineffable quality, an interiority we will have no access to, which hints that in reality all the women who seem to appear have this quality and we’re just too stupid, too culturally mindfucked to appreciate it.

Claudia Cardinale was one of those women.

At the Venice

Film Festival in 1984

When Cardinale appeared on the set of her first film Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), she found herself surrounded by the great talents of Italian cinema: Mastroianni, Totò and Vittorio Gassman. She couldn’t understand what they were saying.

She was to become an icon of Italian cinema but the truth was she didn’t speak Italian. She was born in Tunisia in north Africa into a family of Sicilian immigrants. She spoke Sicilian and French and only began to learn Italian when she was 16.

She was whisked away to the Venice Film Festival having won a beauty competition at the age of 18 and from there to an acting school in Rome, but it didn’t work out. She refused to speak her bad Italian and an abusive relationship saw her return to Tunisia, pregnant and broken. Franco Cristaldi, a producer with whom she’d signed a seven-year contract, stuck with her and she gave birth to her son in secret in England.

Cardinale made film after film, appearing in six releases in 1960 alone. She worked with the best directors often in small roles, but was noticed and vaunted by leading cineastes such as Fellini and Passolini. Those eyes, a face like a cat, like a fawn, Fellini noted, and that sadness.

Little did anyone know the true reasons behind it. In The Girl with the Suitcase, she played a young woman with a secret child born out of wedlock, even as she struggled to see her own son who was being brought up as her young brother back in Tunisia.

Her own suicidal thoughts amid the increasingly controlling behaviour of Cristaldi were a far cry from her role as “Italy’s girlfriend.” Co-stars such as Mastroianni fell in love with her, but she mostly dismissed his feelings as just the usual leading-man romance. She had a brief affair with Jean-Paul Belmondo during a shoot, and with her idol Marlon Brando.

In 1963, she appeared on the Croisette at Cannes with two of the most important films of her career – Il Gattopardo by Luchino Visconti and 8½ by Fellini, who allowed her to act in her own voice. She was now being appreciated as an international star and would make over 30 films in the 1960s, including major roles in Blake Edwards’s The Pink Panther and Sergio Leone’s masterpiece Once Upon a Time in the West.

But behind the scenes Cardinale’s life was being strictly controlled by the Svengali-like Cristaldi, who had become her lover and then would marry her as well as surrounding her with his people. He was one of the most powerful men in the Italian film industry and he knew her secrets. Despite this, she finally broke from Cristaldi and began a long relationship with the left wing Neapolitan director Pasquale Squittiere, with whom she had a daughter.

Cardinale would continue making films and television and find a second lease of life in the theatre making her debut on stage in her 60s. She had released music and wrote her memoir, taking charge of her own narrative.

Suggested Reading

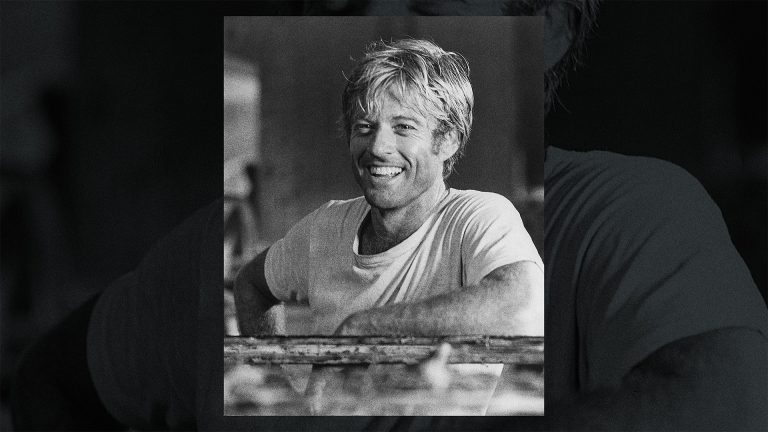

Robert Redford, last of the golden gods

A friend of mine has a bar in Campo San Giovanni and Paolo in Venice. One night, a crew was filming Emma Thompson’s film Effie Gray, and a PA asked if Cardinale, who had a role in the film, might come in from the cold.

She saw my friend’s dog and immediately started chatting about dogs. Hers was old and they’d recently celebrated what she feared would be his last birthday. My friend said she was beautiful, kind, easy to talk to and, just for a moment, the world stood still.