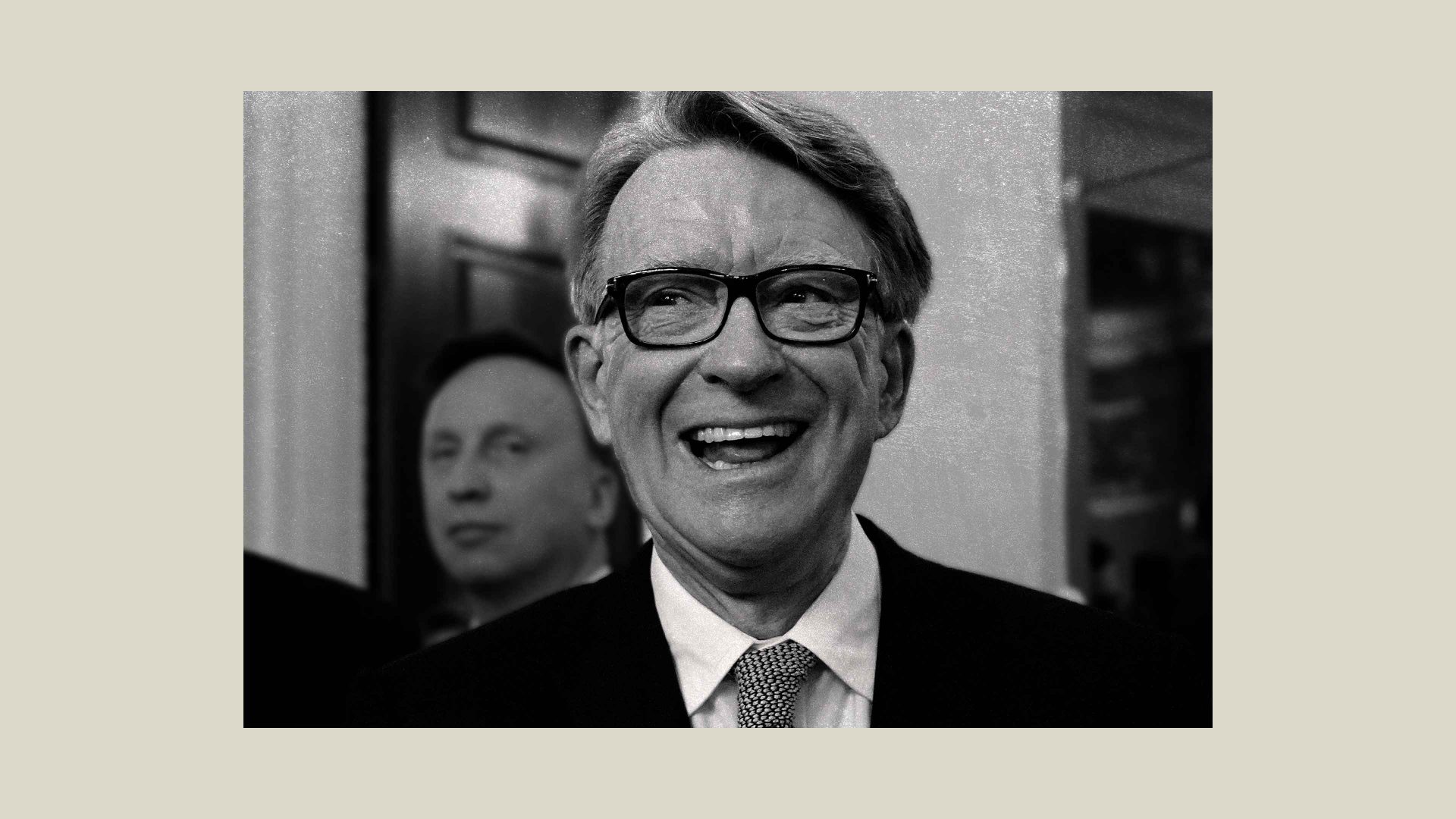

Peter Mandelson, prone on the chiropractor’s table, manifests the calm fatalism of a man who has already survived several reputational slipped discs. We are in the quietly expensive treatment room of his Primrose Hill townhouse, where he has insisted that our interview takes place while his husband Reinaldo gives him a soft tissue massage. He is a highly skilled manipulator, and Reinaldo is an osteopath.

“Intermittently,” begins Mandelson, stripped to a white towel, covered in baby oil, a vinyl headrest framing his face like a diplomatic PVC porthole, “the news cycle has a way of flaring things up.” The final words of this sentence ascend two octaves, as Reinaldo works some gnarly tissue on his thoracic area.

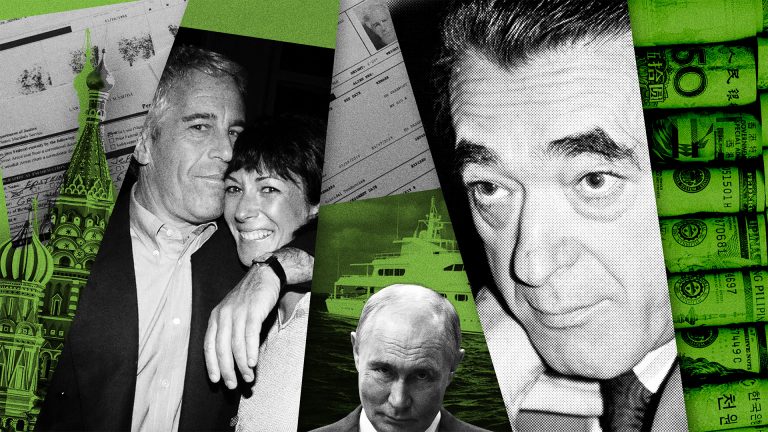

This is an understatement. Despite Baron Mandelson of Foy’s protestations, the latest slew of Epstein files shows that his friendship with the paedophile sex trafficker went from strength to strength, after he had been to prison for 18 months for being a sex trafficking paedophile. It’s almost as if networking and feeding market-sensitive information to the tormentor of children were more important to Mandelson than the children’s lives the tormentor destroyed.

Aware that Mandelson has a razor-sharp eye for optics, I put this to him.

“That is most certainly not the case,” he insists, beneath a laminated poster of the human spine.

This English talent for treating turpitude as a lapse in protocol rather than a cause for severance is well documented. In Brideshead Revisited, friendships survive not because they are blameless, but because severing them would be graceless. The English elite will overlook what is unforgiveable to everyone else provided the offender observes their mores.

When I mention Evelyn Waugh, Mandelson rolls his eyes. Reinaldo intercepts me to explain that Peter’s stress often manifests in his deltoids. Mandelson nods sombrely, as if by carrying the latent tension of nonce-friendship in his shoulder girdle, he was putting the suffering of Epstein’s victims into some much-needed perspective.

“For decades,” Mandelson tells me, “I have been absorbing pressure while appearing to distribute it elsewhere.” There is a pause in the deep tissue massage as Reinaldo, overwhelmed by his husband’s selflessness, stops to exchange an affectionate kiss.

I scroll my phone. Prime minister Keir Starmer’s press conference is on, and Mandelson emerges for air to request I turn up the volume.

When asked if his position is still tenable, Sir Keir repeats previous comments that he “regrets” the decision, and that Mandelson deceived him throughout the vetting process. “I had no reason at the time to know they were lies,” he says of the horizontal man in front of me whose political nickname is The Prince of Darkness.

Born in 1953, Mandelson entered politics not through handshakes and hustings but message discipline and an understanding that power prefers discretion. As an architect of New Labour, the always hovering, always observing, morally flexible insider helped rebrand the party from Michael Foot in a Donkey Jacket at the Cenotaph, to Thatcherism in a pair of y-fronts in a Paris flat.

His career has been punctuated by departures and returns. His absences following ministerial resignations and dismissal as the UK ambassador to the US only ever felt like intermissions.

“Starmer is a fool. I was the best ambassador to the United States this country has ever had,” claims Mandelson as Reinaldo goes to work on his lats. “I really got Donald.”

I ask Baron Mandelson of Foy about trauma.

“Well,” Mandelson says, voice slightly muffled, “I’ve had my fair share.”

“Not yours. Epstein victims.”

“Oh yes, tragic. Very tragic. If only I, Donald Trump, Bill Gates, Noam Chomsky, Elon Musk, Bill Clinton, Richard Branson, or Prince Andrew had known that the man constantly surrounded by young girls who had an island known as Paedophile Island was a paedophile. We could have done something about it.”

“Yes. You’re all quite powerful, aren’t you?” I say. “It’s a shame it’s been left up to the powerless victims to hold them to account.”

“Good point. Very good poooooint,” says Mandelson, as Reinaldo makes a decisive crack without warning. Baron Mandelson of Foy breathes heavily, and we are all genuinely startled – as if collectively registering that beneath Mandelson’s oleaginous surface, there exists an actual skeleton.

Suggested Reading

Trump at Davos: A ‘New Yorker’ profile

I look around the suite. Illuminated by linen-filtered light, the varnished beech shelves are dotted with medical paraphernalia and beige ceramics. Between the folded towels, an anatomical model of a knee capsule, and a sectioned foot with tendons like the rigging on a super yacht, there are carefully placed pictures, totemic trophies of power: Mandelson with George Bush, Mandelson with Prince Andrew, Mandelson in a fluffy white dressing gown tittering with Jeffrey Epstein. He follows my eyes.

“I actually got that out today to get rid of it,” he says of the gold-framed photo that is screwed to the wall.

Inevitably, I think of Camus. The most unsettling feature of The Plague is how long everybody goes about their business as normal. The rats die one by one, the signs are unmistakable, yet dinners are still attended, appointments kept, and friendships maintained. Likewise with Epstein. For the men getting so much banality out of it, to acknowledge that he could operate in plain sight would have required an intervention too seismic to contemplate.

The fact that the Epstein files provide overwhelming evidence that corrupt power is wielded through the persistence of elite networks does not lead to remedy. The plague does not spread because no one notices it; it spreads because noticing it is socially inconvenient. Scandal is not denial, but delay.

And if scandal is the tax paid by power, Mandelson has always preferred to pay in instalments. Once his shoulders relax and the vertebrae loosen, he will soon feel better again, not about Epstein’s victims, but in the knowledge that reputations, like posterior chain muscles, are very resilient when handled by the right people.

Of all the interviews I have done, other than Eamonn Holmes, this one feels like the most pointless. Peter Mandelson has been telling us exactly who he is for decades and daring anybody to notice.

Pertinently, as I leave as the police arrive. Mandelson does not look over his shoulder. I cannot tell if this is through overconfidence, or because Reinaldo’s Epstein-funded osteopathy course wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.

More from Henry Morris at mrhenrymorris.substack.com