The youth of today have never had it so good. Dinner arrives at the tap of a button. Every film, every song, the answer to every question is available on demand. We can fly across continents, or simply scroll through them from the sofa. We will live longer, healthier lives, armed with tech that no generation before could have imagined. We can do anything we want. Except, of course, when it comes to the things that really matter.

Beneath this veneer of endless choice, true freedom is harder to come by. While young people may enjoy the surface-level spoils of modern-day capitalism, for many, financial pressures, insecure jobs, and rising living costs are turning their lives into relentless compromises.

Steph*, 29, thought she was building freedom. On paper, she has everything independence is meant to guarantee: a flat bought without parental help, a partner, and a salary above the national average. Yet after two rounds of redundancy, soaring bills, and a mortgage that barely leaves room for choice, she feels trapped. “I’m in survival mode,” she says. “One boiler breaking or job loss from being bankrupt.”

For young people like Steph, the milestones that were once intended as springboards – a career, a home, a family – have become anchors, holding them in place rather than letting them soar.

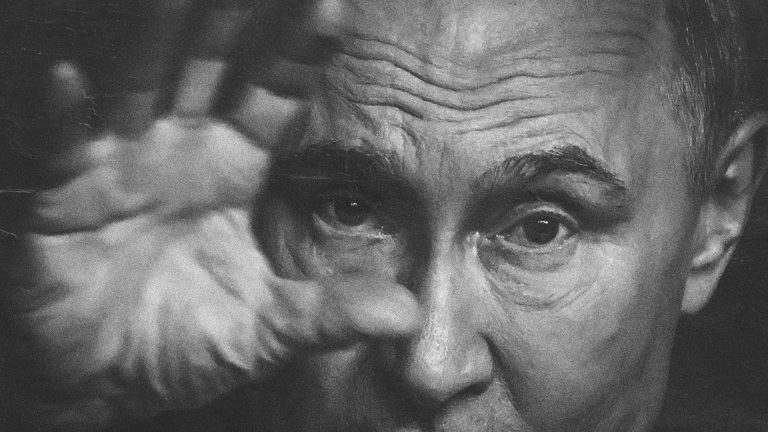

Since the mid-1970s, British politics has been built on the belief that owning a home was both a moral virtue and a route to true autonomy; the “bedrock of a free society” according to Lord Heseltine. Half a century on, that promise has curdled.

Decades of underbuilding and policies that transformed houses into investment assets have left a market that favours the few. Now, housing is now the most visible trap for young people.

Scarcity drives prices higher, rents spiral, and every life choice – from where to work to whether to have children – is held hostage by the precarity of their homes. Renters spend on average 34% of their income on housing, while mortgage payments consume 19%, leaving little room to pivot careers or relocate. Since 2022, average rents for new tenancies have jumped 21%, outpacing wage growth and mortgage costs alike.

Steph’s story illustrates this pressure. Home-ownership did not liberate her. Weeks before completing on her flat, redundancy hit, forcing her to take the first available job rather than follow her ambitions, or risk losing her mortgage offer.

Now, as interest rates push her payments even higher, she sees no way out of what she calls the “golden handcuffs”: “Your job pays you well, decent colleagues, great perks […] But the job just isn’t what you want to do anymore. Well – something has to budge, because if the pay is good and your lifestyle is built from this – it’s really hard to go back.”.

Wage stagnation makes the squeeze even tighter. Early-career workers today earn barely more than their peers did in 2010. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, average pay is just £16 a week higher in real terms than it was at the last election 15 years ago – the slowest wage growth in modern history. Young people have been hit hardest: their pay fell further than any other age group after the 2008 crash, and it has never truly recovered. The result is a double bind: housing costs spiral while wages stand still.

Solutions exist on paper. Labour’s Employment Rights Bill promises stronger protections, fairer pay and more secure contracts for workers, designed to prevent job precarity and boost the money in workers’ pockets. But already, there are whispers that business pressure will see it watered down before it reaches the statute book.

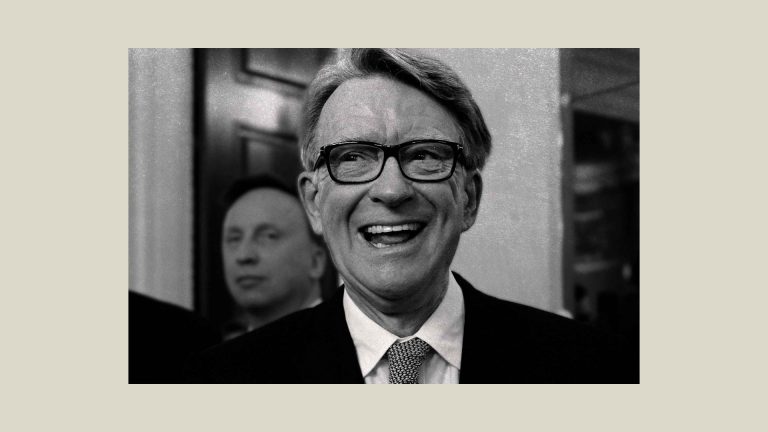

Meanwhile, as housing supply remains strangled, even the most generous uplift in pay or job security would still leave young people shackled to a hostile market. “There is no intergenerational contract without sorting out housing,” says Professor Bobby Duffy, author of Generations: Does When You’re Born Shape Who You Are?. “It means restarting a social housing programme at scale, reforming private renting, and building more homes.”

The government’s pledge of one million new homes already looks shaky. The obstacles are familiar: developers, landlords, NIMBYs. For many, the issue is not technical but political. “Governments are not listening to what young people – or the general population – actually want,” argues Alec Haglund, a political economist at the Positive Money think tank. “Perhaps they’re scared of doing so, because it would require a radical transformation of the economy we’ve experienced over the past 30 years.”

For Liz Emerson, CEO of the Intergenerational Foundation, housing may be the sharpest edge of the crisis — but it is merely the inevitable outcome of deeper, structural imbalances. Decades of choices, she argues, have hit the young hardest while pensioners are protected by cowardly politics.

Student loans now leave the average graduate £53,000 in debt — the highest burden in the developed world. Add in rising taxes, welfare cuts, and ballooning pension bills, and the result is a steady stripping away of young people’s economic freedom.

“We are seeing the systematic loss of economic position of younger generations over time,” Emerson says. Yet governments have “chosen to pass the pain on,” leaving under-40s “bootstrapped – economically – in every area of their lives.”

“The people holding the country to ransom are the grey votes,” she adds. Politicians admit privately they know the problem, but confess they can’t “sell it on the doorstep.” In the end, the votes of pensioners matter more than the future of the young.

When I reached out to my peers on social media to ask them about the “lock-in effect,” responses flooded back with bleak familiarity. Yet what struck me was not only the ubiquity of frustration, but its uneven distribution. Class, gender, and family expectations all shape how far young people can stretch their already limited options.

Lauren*, 26, embodies this. She shares a two-bedroom terraced house with her husband, has a solid salary as a sales manager, and a mortgage. She dreams of retraining to work in law or a charity, but a career change would mean a pay cut she cannot risk.

Lauren is trapped by her mortgage, bills, and the cost of living. But it is not just her career that is suffering as a result. “If I felt financially secure, I would leave my husband,” she admits. “He spends most of his time ignoring me and is a bit manipulative and emotionally abusive.”

Suggested Reading

The rise of the early downsizers

For Lauren, her gender and class magnify the lock-in. As a woman and the first in her family to attend university, she feels pressure to be “seen to be doing well”. Steph voices a similar reflection: “I would feel less stuck at this moment in time if I were a man, because I wouldn’t have to think about the implications of children as much. As a woman nearing 30, I can’t just work extra jobs to supplement my income as I’ve always done before.”

These pressures are not abstract; they can be dangerous. Many women find themselves in housing or relationships that are emotionally or physically unsafe, yet they cannot afford to leave. Gendered economic inequality compounds this risk: across England, average rents consume 43 per cent of women’s median earnings, compared with 28 per cent for men. Not surprisingly, over two-thirds of women still living with an abuser cite concerns about future housing as a barrier to leaving.

That illusion of choice – the idea that the freedom to pick an app, stream a series, or curate a social media persona compensates for shrinking real freedoms – feeds into the lock-in. Duffy points to public discourse, epitomised by Kirsty Allsopp’s infamous claim that young people could afford homes if they just gave up Netflix or the gym, as arguments that let victim-blaming flourish, conflating lifestyle choices with life chances: brunch spots and gym memberships on one side; the ability to leave an unfulfilling job, buy a house without parental help, or start a family without financial ruin on the other.

What’s striking, Duffy notes, is that young people have “blame themselves”. In research conducted by Duffy’s university, Gen Z were as likely as older cohorts to agree with Allsopp’s comments, even though they’d had “lots of the support that previous generations took for granted taken away from them”.

“This is actually a generation that’s got a strong sense of personal responsibility for outcomes because that’s the culture that they’ve grown up in,” Duffy explains. “They’re not aware that they are being locked in by structural forces.” In other words, meritocracy has curdled into a trap, recasting systemic unfairness as personal failure.

This private shame is compounded by the awareness of wider inequalities; the yawning divide between the haves and have-nots. For many young people, family wealth is the only route to milestones such as home ownership.

In 2022–23, 37 per cent of first-time buyers relied on family help, up from 27 per cent the year before. But relying on parental aid often comes with strings attached. Among Gen Z, 56 per cent say such support shapes their life choices, creating pressure to prioritise others’ expectations over their own.

Admitting this privilege in front of friends can feel awkward, even taboo. Milestones once celebrated as personal triumphs — buying a house, having children, planning a wedding — have become markers of inherited advantage.

The gulf is stark: Children of homeowners and graduates often receive up to six times more than peers whose parents rent. Haglund notes that this dependence on the “bank of mum and dad” doesn’t just skew opportunity, it also fractures solidarity. Many beneficiaries, he argues, are acutely aware their position is “purely luck, rather than my own doing,” a realisation that breeds guilt and embarrassment. The result is silence: those who benefit rarely admit it, while those left out feel the injustice all the more sharply.

For Haglund, the barrier to reform are not simply economic but cultural — a resistance that stops policymakers tackling the root causes. Without intervention, he warns, “these issues will only get exponentially worse.”

When governments fail to invest in people, education, and productive industries, money flows instead into assets, widening the gap between those who own and those who do not. The result is growing inequality, lower productivity, and steadily falling living standards for younger generations. To make up the shortfall, governments of all parties rely on taxing wages rather than wealth, creating “a disjointed economy that works for the interests of very, very few.”

For Emerson, young people have a vital role to play in standing up for their own futures, which means honest conversations about the struggles they’re facing. “What’s really hard is finding those young people who are willing to admit to their peers that they’re not doing as well, who will sit in a pub with people and say ‘well, actually, I’m really struggling. I can’t afford to pay my bills, and my career isn’t going the way it should be’.”

“Younger generations [have] to stand up for their own generation. Say this has to stop. We need a new intergenerational contract.”