Mention Monopoly, and someone will inevitably respond, “oh, wasn’t it originally supposed to be a critique of capitalism?” This is the Monopoly Fact™, and while it’s half-true, the full story is more prickly and elusive. It’s also the most eloquent indictment of the American Dream in board gaming’s history.

Growing up, the story I heard was that Monopoly had been invented by an out-of-work salesman during the Great Depression. In the midst of the economic cataclysm sweeping America, he created its antithesis – a game of acquiring riches, and triumphing against the odds, a form of wish-fulfilment for a country sorely in need of some escapism.

This was the great irony in the Monopoly creation myth, the twist that made it a fun anecdote to share: the wildly successful game all about money was invented by someone who was poor and unemployed, but who went on to become very wealthy off the back of it.

And that guy really existed: his name was Charles Darrow, a domestic heater salesman from Philadelphia. He really did lose his job in the 1929 crash, and in the early 1930s he really did start making prototypes of the game at home with his wife and son. He got a copyright for the game in 1933 and in 1934 offered it to Milton Bradley, who rejected it, as did Parker Brothers.

Meanwhile, Darrow was producing and selling it privately to Philadelphia department stores. Seeing this retailer interest, Parker Brothers bought the rights. Monopoly was 1935’s bestselling board game. Darrow became a multimillionaire, and retired at 46, devoting the rest of his life to travel, orchids and photography.

For 40 years, that was the story, printed in precis in the rulebook of every copy sold. And maybe it would still be today if it hadn’t been for a San Francisco economics professor called Ralph Anspach. In 1973, he published a game he called Anti-Monopoly, intended to serve as a critique of what he saw as the original’s tacit endorsement of monopolies as something to strive for.

In Anti-Monopoly, players break up trusts, oligopolies and monopolies by landing on them and placing indictment chips – essentially launching legal cases against steel, aluminium, gas and car conglomerates. Visually, the original edition looks very similar to Monopoly, with a square board, and companies grouped by colour like Monopoly’s properties. Anspach’s stated purpose was to teach an economic lesson about how harmful monopolies are to a free-market economy. Parker Brothers promptly sued him for copyright infringement.

In the process of preparing his defence, Anspach began researching the history of Monopoly, and discovered that the official account of its creation was inaccurate in several respects. Many of the people involved in its initial development were still alive, and Anspach produced testimony from them in court, including Darrow’s widow. As a result, the truth behind Charles Darrow’s “invention” finally emerged.

The year was 1865, and Henry George was about to do something desperate. His wife had just given birth to their second child, and he and his family were literally starving. Leaving their bare lodgings, he staggered out on to the streets of San Francisco with a single, terrible purpose.

In his own words: “I walked along the street and made up my mind to get the money from the first man whose appearance might indicate that he had it to give. I stopped a man – a stranger – and told him I wanted $5. He asked what I wanted it for. I told him that my wife was confined and that I had nothing to give her to eat. He gave me the money. If he had not, I think I was desperate enough to have killed him.”

Henry George eventually became an influential social theorist and economist whose 1879 book Progress and Poverty went on to sell millions of copies globally. The theories he proposed came to be known as Georgism. Central to Georgism was his conviction that poverty, recessions and social inequalities arose from private ownership of land. Being a finite resource, the value of land grew as a population increased, allowing owners to charge increasingly exorbitant rents.

George advocated for a single, universal land tax based on its value, rather than taxing labour, arguing that the land and natural resources belonged to everyone. He did not, however, consider himself socialist or communist, arguing that both had a “fatal flaw” – the harmful encroachment on the freedoms of private individuals.

One of many people who warmed to his ideas was a feminist activist, poet, author, stenographer, actor and inventor called Lizzie Magie. At 26, she invented and patented a process to make it easier to feed paper through typewriter rollers. In 1902, she began designing a game based on Georgist principles. She called it the Landlord’s Game, and in 1904 received a patent for it.

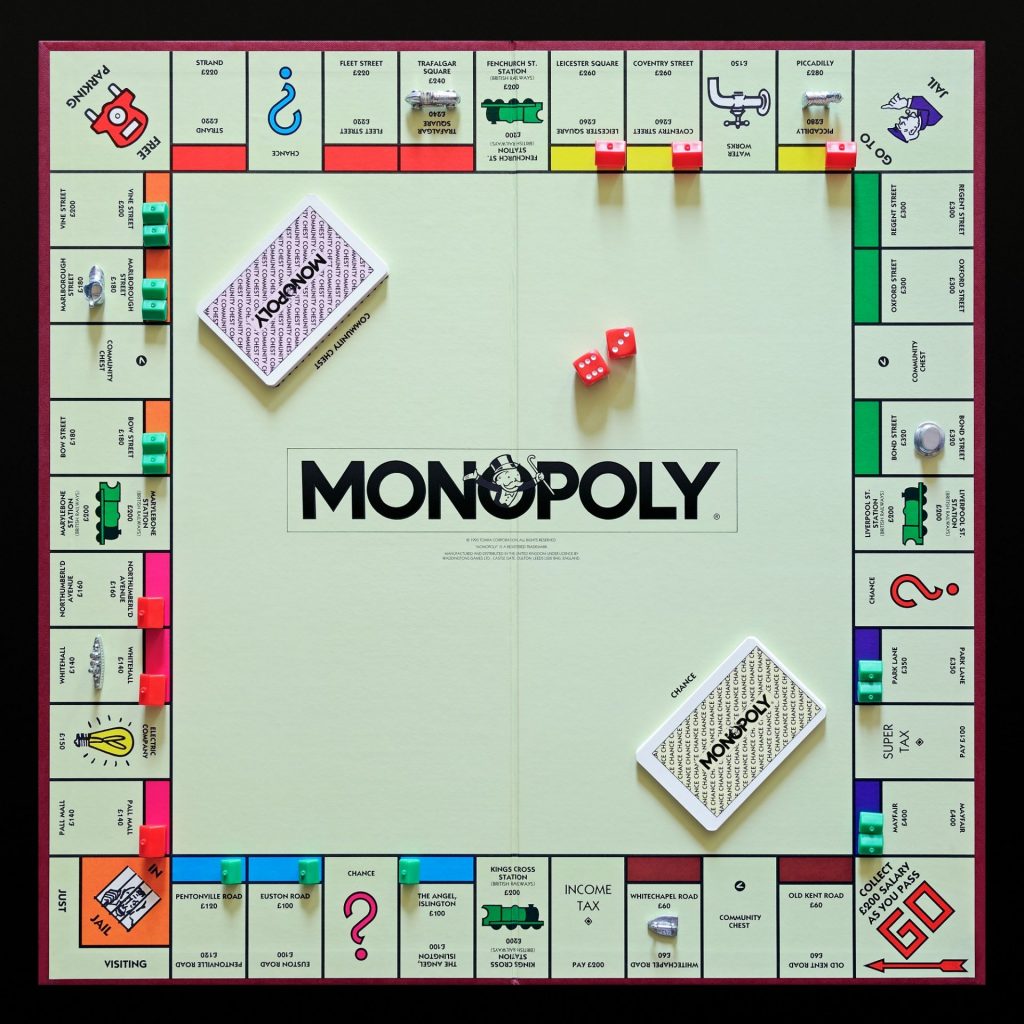

The board in the patent drawing is recognisably the Monopoly board, with its square track round the outside, comprising nine rectangular spaces a side, connected by large corner spaces, with railway stations on each middle space. FREE PARKING is a PUBLIC PARK, there’s the familiar JAIL in one corner, and various rectangular properties with sale and rent prices.

Magie’s purpose was to show players how allowing private interests to buy land and charge rent on it inevitably led to the concentration of wealth in a few individuals while the rest became impoverished, and how the introduction of George’s “single tax” would resolve this.

Unlike Monopoly, the game did not continue until one player remained, but ended after a “predetermined number of circuits of the board”.

Magie did not aim, especially, to make the game fun, and certainly not to make it fair. One rule she added stated that if a player rolled a two, they had been “Caught robbing the public – take $200 from the board. The players will now call you Senator.”

In the years that followed, a few hundred handmade copies of the game produced by Magie and her fellow Georgists were sold in a handful of shops and shared in Quaker and progressive academic circles. An edition was published in Britain in 1913. Along the way, players made annotations and revisions and created their own versions.

Several groups changed the properties to correspond with local street names, as happened when Ruth Hoskins brought a version back to her Quaker friends in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The streets she chose, and the prices added by another group member, Jesse Raiford, are those still used in America today.

Years later, in 1964, Jesse’s brother, Eugene, would type a letter to newscaster Vince Leonard at Philadelphia station WRCV-TV. He wrote: “Last Tuesday, at about 6.12 pm, I saw someone interviewing Charles Darrow, the ‘inventor’ of Monopoly… I do not know who invented the game but I can tell you how it came into the hands of Mr C Darrow.”

He went on to explain that, back in the winter of

1932-33, he and his wife, “newly married and being anxious to entertain friends”, brought a game to Philadelphia from Atlantic City, gifted by his brother, Jesse. They put on “many Monopoly parties” for friends, including Charles Darrow and his wife, who were given their own copy.

“It was not long after that,” Eugene’s letter went on, “that Mr Darrow ‘invented’ the game and later made a business arrangement with Parker Brothers.”

Much of this failed to excite interest, except among experts. It was not until Ralph Anspach’s legal dispute with Parker Brothers over Anti-Monopoly, however, that his digging around brought the game’s history sharply into the public eye.

The legal battle raged on well into the 1980s. The Monopoly trademark was briefly nullified, passing into the public domain.

The case was finally settled in 1985, with Anspach receiving compensation and retaining the ability to publish Anti-Monopoly, but Monopoly returning as a trademark of Parker Brothers. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ conclusion was clear: “reference to Darrow as the inventor or creator of the game is clearly erroneous”.

Robert Barton, who had been the president of Parker Brothers, testified that he had learned of the Landlord’s Game and its various spin-offs as early as 1935. Darrow had offered, in correspondence, to sign an affidavit that he was the game’s inventor, but Barton testified that he had not believed him. Darrow’s application for a patent had failed when Magie’s previous patents were discovered, at which point Parker Brothers had quietly purchased the rights to the Landlord’s Game and bought up existing copies.

Today, Lizzie Magie is widely recognised as the inventor of most of the core features of Monopoly as we know it. Darrow’s only real contribution was hiring an artist to draw the symbols for the Electric Company, Water Works and Railway Stations.

Suggested Reading

Carsten Höller’s bored games

Monopoly’s incredible success has resulted in key parts of the game – especially the “Get Out of Jail Free” card – passing into common parlance. It has expanded to a broad portfolio of branded merchandise. There are Monopoly slot machines, Monopoly video games, multiple new board and card games such as the 15-minute card game Monopoly Deal, Monopoly Bid and Monopoly: Cheaters, plus hundreds of local and themed versions of the original game, many of which make little to no sense and feel instantly dated: Monopoly: Love Actually, Monopoly: HM Queen Elizabeth II, Monopoly: Arsenal FC 17/18, Monopoly: David Bowie.

In department stores and supermarkets, Monopoly, now owned by multinational toy and game conglomerate Hasbro, dominates shelf space. It muscles out competitors by sheer volume.

This is a great irony of Monopoly. Its history, presented as a capitalist success story, serves as a textbook indictment of an unfair system. A shameless opportunist, enabled by a company which knew how to exploit the legal system, got rich by profiting off the uncredited labour of others. Some consolation then, that the game’s inventor is finally getting the recognition she deserves.

Looking at Lizzie Magie’s 1904 patent, we see many features that just aren’t present in other roll-and-move board games of the era: instead of a linear track, or a spiral, the track loops round on itself. There’s this striking square circuit, which, as she writes in the patent, has “corner-spaces, one constituting the starting point, and a series of intervening spaces”. Between the corner spaces, the railway stations in her version act as hazards, where you have to pay five dollars if you land on one. Every time you complete a circuit, you get money – and that money, rather than getting home first, is what wins you the game.

At the time, the endless square board, the corner spaces and railroads, and receiving money every time you completed a circuit, felt fresh and innovative. And, to the general public, they were. There’s just one issue: Lizzie Magie didn’t invent any of them.

Zohn Ahl was a game played by the Kiowa tribe of Oklahoma in the 19th century. It features players throwing dice and racing round an endless square track with four large corner spaces connected by four straights of seven spaces, each divided by a “creek” in the middle. Players don’t win by coming first – there is no finish line – but by winning all the counters in a pool, including those acquired by opponents. Each time you complete a circuit, you receive a counter; you can also lose a counter by landing on one of the creeks – and thus falling in – or if another player lands on you.

In 1898, ethnographer and games historian Stewart Culin published his book Chess and Playing-Cards, which included a description of Zohn Ahl. He included a diagram of the board.

Lizzie Magie and Stewart Culin may have been friends, or she may have seen Zohn Ahl on display at an ethnological exhibition in Philadelphia in 1893. It is entirely possible that, in one way or another, she was exposed to an image or description of the game, and took inspiration from it. Yet the purchasing of property is definitely not present in Zohn Ahl, and Lizzie Magie deserves recognition for her work while Charles Darrow ought not to have received a penny.

But the idea that a white settler took – wittingly or otherwise – a Kiowa game, and turned it into a parable about the injustice of stealing land from its rightful owners would be the final, crowning irony of Monopoly’s complicated legacy.

The Game Changers: How Playing Games Changed the World and Can Change You Too by Tim Clare is published in paperback by Canongate