Just before I arrived in Costa Rica, a German couple was killed on their remote retirement property: some sort of robbery gone wrong. I might not have known, were it not for the person on the flight who mentioned it. Or the taxi driver from the airport who did the same. I assume the receptionist at the hotel would have too, but it was 3am, and she was all but sleepwalking.

The fixation was odd. But then something like this is unusual in Costa Rica, or it would have been a few years ago. Because for a while now Costa Rica has been slipping into the kind of violence that is common in so much of the rest of Latin America. And Costa Ricans are appalled, enthralled, by the change.

It comes after many decades in which Costa Rica has been a regional exception: peaceful, green, democratic. That’s a point of pride for Costa Ricans, or Ticos, as they call themselves, who tend to trace the difference back to the decision, taken in 1948, to abolish the Costa Rican army.

This occurred after a brief but bloody civil war, and it made Costa Rica one of the few nations in the world with a constitution that prohibits a standing army. The idea was that money wouldn’t be spent on arms, but on healthcare, education and culture. It pitched Costa Rica against the current of the times: by 1977, it was one of only four Latin American countries that was not ruled by a dictatorship.

There’s an iconic photo of the moment when the rather portly president, José Figueres Ferrer, swung a sledgehammer at the battlements of the barracks in the centre of San José with his eyes closed, perhaps a little shocked to feel it break so easily into pieces.

Those barracks are now home to Costa Rica’s national museum. Painted a mustard colour and scored with slits and crenellations, it might still look somewhat military, but the atrium is full of butterflies. They flutter and glide around visitors, and settle to feast on plates of pineapple. On the door it reads: “Please don’t let the butterflies out.”

It’s easy to see how Costa Rica won a special place in the imaginations of the kind-hearted. But in truth it was never quite the paradise people wanted it to be. It’s even less so now.

While I was sitting on a bench outside the museum, a man strode over to me. He stopped, looked around a little dramatically, then told me to put my phone away. “There’s lots of criminals around here,” he said. “They target tourists.”

Suggested Reading

Dubai: a safe space for hypocrisy

I did, and squeezed my bag between my legs, suspecting he might be some sort of distraction. But apparently he was just another concerned and anxious Tico. San José, he said, had changed with the pandemic: unemployment, crime, drugs. “Cocaine,” he said simply, before brightening all of sudden: “Have you been to the old town yet? There’s a sloth sanctuary.”

Later that day, Rodrigo Campos, a security expert, smiled when I told him about this. “We’re all amateur ornithologists and entomologists,” he said, before confirming what the man outside the museum had told me. The cocaine business has run through Costa Rica for decades, but it is much more violent nowadays.

The Pacific is the key drug trafficking route up into North America. Speedboats set out from Ecuador and Colombia and need to refuel three times on their way to the US-Mexico border. One of those stops tends to be on Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. An alternative is that the traffickers might unload the cargo there, then transport it across Costa Rica to be hidden in the many containers of bananas and pineapples that leave Limón, the Caribbean port, bound for Europe.

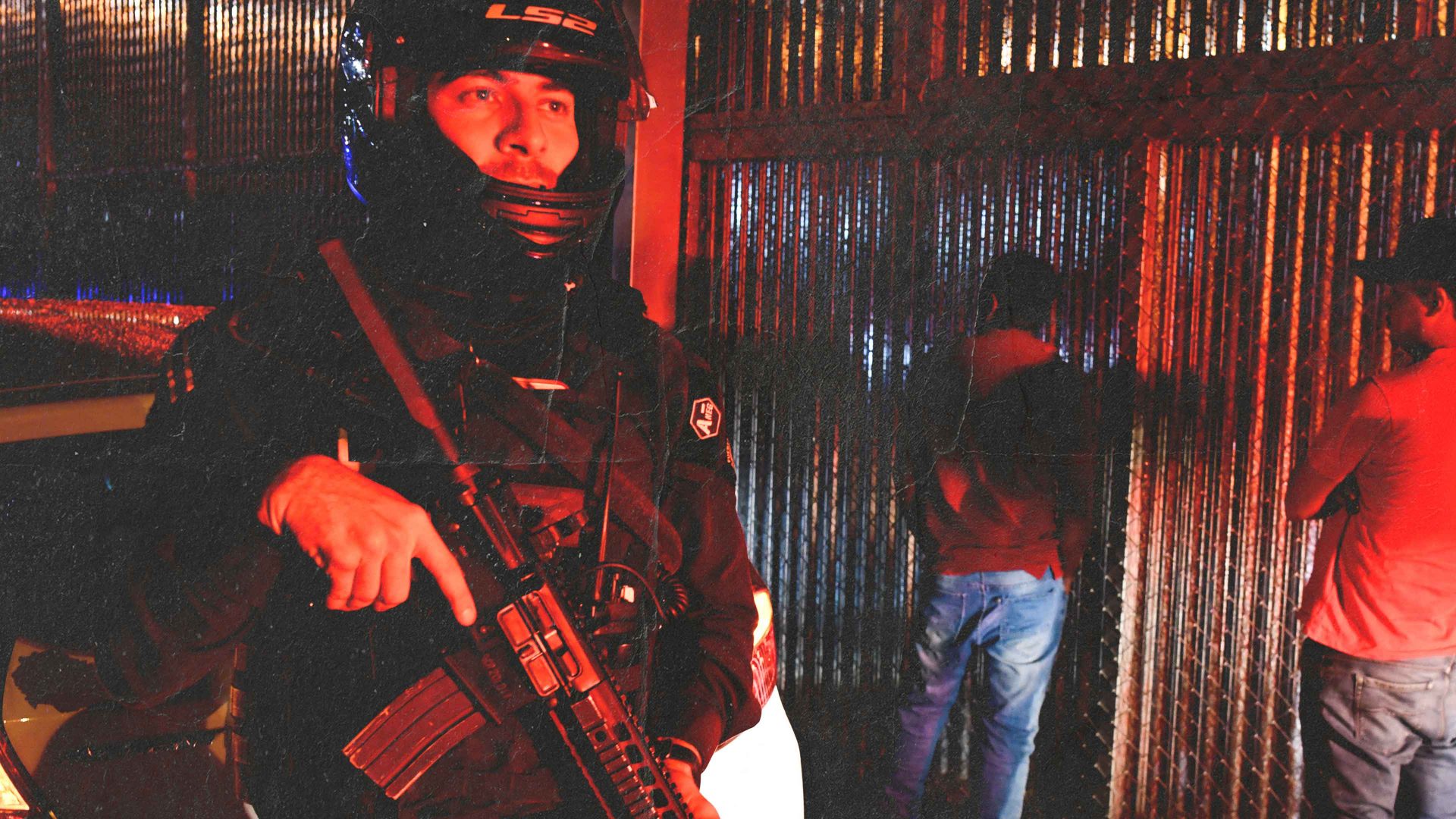

But traffickers don’t carry cash: they tend to pay for services in product. That means hundreds of minor criminal groups in Costa Rica end up selling cocaine on the local market. And they’re all competing for business, with a deep pool of pistol-wielding young men – sicarios – willing to get involved in violence.

“Between showing up on the police’s radar and ending up in the morgue, these young men tend to last five years,” said Campos. “It’s a short criminal career. And a whole generation is being decimated.”

Still, while violence in Costa Rica has increased, it remains well below the levels seen in Mexico. And yet Ticos seem to talk about it a lot more than Mexicans. Perhaps that’s because what people really notice is change, especially change for the worse, and Costa Rica’s star is falling.

When I put it to Campos, delicately, that Costa Rica might be becoming a little more like the rest of Latin America, he corrected me: “We are already 100% Latin American.”

That night, on the way back to the hotel, everything outside the car window seemed a shade more sinister. The taxi driver kept eyeing me in his rear-view mirror while I checked that the blue dot on Google Maps was moving in the right direction.

Then the taxi driver brought up the murdered German couple. He had new details: they were found tied up and buried, with bullet wounds. There were blood stains all around the house, as if there had been some kind of struggle, or as if perpetrators had dragged them through the rooms demanding to know where the valuables were.

He shook his head. “Maybe a Tico would rob you, fine,” he said. “But they wouldn’t kill you just like that.” With two hands on the wheel, he jutted his chin up instead of snapping his fingers. “The killers must have been Venezuelans or Nicaraguans,” he decided.

We rolled up to my hotel. Perhaps the receptionist was napping again – she took an age to appear and unlock the gate. All the while the taxi driver sat there idling, almost like a chaperone.

Then he leaned out of the window, with one last thought.

“See if you can get to the Tortuguero park,” he said. “You can see the turtles on the beach.”