When I was in Tel Aviv last year, I vividly remember a conversation with an Israeli colleague about the future of Gaza, if there could ever be an “after Hamas”. Suddenly she asked: “How did Germans get rid of the Nazi ideology after the war?”

“Not sure we did, actually,” I replied. The change of mindset, if you want to call it that, didn’t exactly come from within.

First, there was total defeat. Then, for West Germany, siding with the western Allies was the only way to keep the Soviets out – a choice East Germans didn’t have. And finally, the 1950s economic boom in the west helped paper over many uncomfortable truths.

A newly published book devotes a lot of paper – 938 pages, to be exact – to uncover them. And not just anywhere: the four historians write about former Nazis at the heart of Das Kanzleramt, the chancellor’s office, the power hub of the young German democracy.

One name that stands out is Hans Globke, chief of staff to Germany’s first Bundeskanzler, Konrad Adenauer. During the Third Reich, he helped draft the Nuremberg race laws and introduced measures to identify and stigmatise Jewish citizens, such as marking passports with the letter “J.”

And yet, Adenauer, who was kicked out as mayor of Cologne by the Nazis and was arrested several times by the Gestapo, defended his right-hand man. Globke’s portrait, like those of all his successors, still hangs in the “ancestral gallery” in one of the Chancellery corridors. There is an explanatory caption pointing out that the legislation co-authored by Globke helped lay the foundation for the persecution, deportation and murder of Jews and Sinti and Roma. It was added in… 2020.

Globke’s case is well known. The new book – drawing on four scientific studies – expands the lens to look at other staffers and how the chancellery handled the Nazi past. The results are sobering.

The Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) had some 8.5 million members. Millions more were involved in Nazi injustices and crimes, either by committing them, profiteering from them or turning away.

Under Adenauer, up to 38% of senior civil servants had an NSDAP background, according to the authors. These HR continuities stretched well into the early days of Helmut Kohl’s chancellorship – with four chancellors between him and Adenauer – when the last of them reached retirement.

Suggested Reading

The dark shadow of the AfD hangs over German politics

Earlier research from Kassel University backs this up: of 283 top civil servants in the Bonn federal ministries and the chancellery, at least 105 were confirmed NSDAP members. Of the 51 ministers of the same period, 13 are known to have been members of Hitler’s party. Only 15 of the 334 top officials and government politicians had held positions in central NSDAP offices, however. In seven cases, there is evidence of violent acts, such as participation in a pogrom or approval of deportations to concentration camps. Eleven had been SS, SA or SD officers.

Given the extent to which postwar West Germany relied on elites who had simply discarded their Nazi affiliations, it’s no surprise that proven anti-Nazis were few and far between. Just 21 of the 334 had been imprisoned, 60 had suffered material losses, for example through the expropriation of assets. Only 17 individuals are known to have been part of the resistance.

So why did Adenauer – a devout Catholic determined to reconcile with victims and instrumental in establishing ties with Israel – accept such a tainted workforce? Interestingly, Peter Altmaier – Angela Merkel’s former chief of staff and thus a successor of infamous Globke – recently explored this question in Der Spiegel. “As chancellor,” Altmaier writes, “Adenauer was well aware of the majority’s desire to ‘draw a line’ under the past and bring an end to denazification and reckoning,”

Suggested Reading

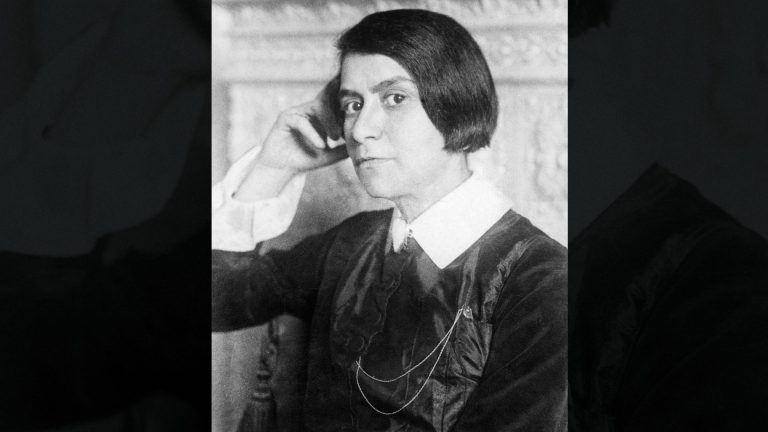

Else Lasker-Schüler, the poet who defied the Nazis

He has a point. It wasn’t until the Auschwitz trials in the mid-1960s that a younger generation began to ask hard questions. Altmaier argues that Adenauer overlooked past wrongdoings because his priority was stability: building democracy, prosperity and a western alliance, not recruiting spotless staff. He needed a well-oiled, loyal civil service surrounding him, because he was facing plenty of opposition elsewhere: against the free-market economy, the pension system, rearmament, Nato membership and Westbindung (leaning strongly towards the west) in general.

His aim, Altmaier suggests, was that everyone buy into democracy – not just the few who had opposed the Nazis. Is there a lesson in this? Maybe that stability sometimes gets built with very grubby hands. And the price of it should never be amnesia.