There’s a new book out in Germany – Machtgebiete (Spheres of Power). Fifty top female executives describe how, despite climbing the greasy pole, they’ve confronted with bias, barriers and mansplaining. Kathrin Anselm, now at Airbnb, recalls a board meeting with a dozen men where a senior partner purred: “Ah, Frau Anselm, I can’t focus on the meeting – your legs are far too distracting.” The CEO said nothing. Anselm quit soon after.

When reading this, I was reminded of a woman telling me about applying for a senior job at the state-owned railway Deutsche Bahn (DB) about 15 years ago. The reply: “But you have three children, there’s no way you can possibly do this job.” She didn’t get it. She’s since proved them spectacularly wrong in other top positions.

Today, the Bahn board now has three women out of seven. One of them, Evelyn Palla, is about to be crowned the new CEO – or, as the tabloids put it, “Queen of Chaos Central.” Born in Bolzano, she’s Italian. Hardly shocking: trains in bella Italia are more punctual than German ones.

Anyone who came for the Euros last year will have sampled the joys of German rail: cancellations, delays, overheated compartments, freezing compartments, overcrowded compartments, shaky wifi, and the dreaded bistro announcement: “Sorry, no hot water, kaputt”. Yes, I’ve endured the same in the UK, but still.

Predictably, Palla’s appointment raised eyebrows. It is held against her that she lives in Vienna (where she sat on the board of Austria’s railways, ÖBB). She reportedly wasn’t even first choice – others turned it down. Small wonder. DB Tower in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz is notorious as a nest of schemers. The task is Herculean: renovate the creaking network while keeping trains running. There is money – €107bn to 2029 – but passengers won’t tolerate endless standstills. And DB has a spectacular knack for failing at the balance between punctuality and modernisation.

This week, minister of transport Patrick Schnieder (CDU) unveiled the new “strategy for satisfied customers”: making 70% of trains punctual by 2029. Aim low, folks. But anything else apparently is completely unrealistic.

For the first time in history, at the beginning of July less than 40% of long-distance trains were on time for three consecutive days. In the 1990s, punctuality was at 85%. Before the Bahn redefined “on time” as “less than six minutes late”.

The official culprit is “dilapidated infrastructure.” True, 41 routes need full renovation by 2030. But, according to the ministry, only 18% of delays are down to that. Half stem from an overloaded network. Rail traffic has soared over three decades, while the network has shrunk. With no buffers left, even a cyclist needing two minutes longer to board can cause a nationwide domino effect.

Suggested Reading

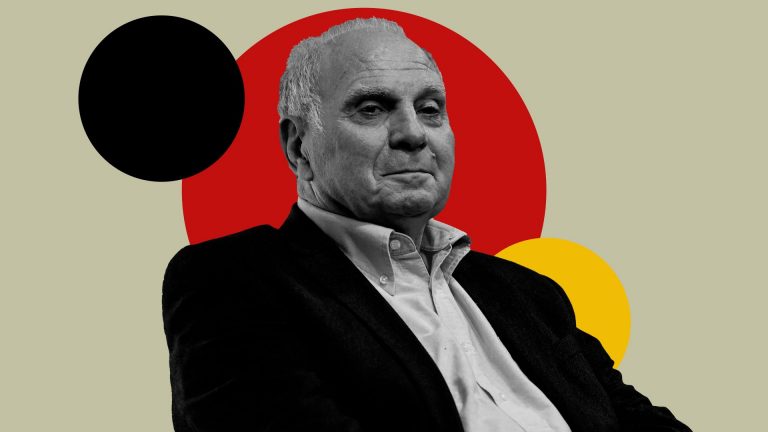

Uli Hoeneß and the summer’s record-breaking transfer frenzy

Congestion is made worse because, unlike France or Japan, where high-speed trains run on their own tracks, Germany mixes fast inter-city services, local stoppers and freight on the same rails. Cost-cutting in the 2000s removed passing loops and switches, when DB was being prepped for privatisation – a plan ditched in the 2008 financial crisis. The same applies to the ETCS – the European Train Control System. It digitally registers travelling trains and calculates braking distances. This could increase capacity by up to 20%. But only the inter-city fleet is equipped with it.

So why Palla? Results. As head of DB Regio, the 52-year-old mother of three stood out by generating €103m in profit in the first half of 2025, following a significant loss in 2024. It is the only profitable Bahn branch and not as notoriously delayed as the rest of the network. Company insiders describe her as “cool,” “analytical,” and “distant”. She has no issue with making “clear, even tough decisions.” Which is exactly what DB needs.

“The last few weeks have been paralysing,” one manager told me. “Everyone just watching each other, suspicious and cautious, as they knew a change at the top was coming.”

The size and structure of the board, widely blamed for DB’s woes, will now be under review. But next to passengers and the Bahn hierarchy, Palla must tactfully placate the huge range of stakeholders: the Bahn union EVG, freight chiefs, state premiers, municipal officers, regional transport ministers, and of course the federal government.

But if staff shortages threaten to cancel a service, at least she can literally drive the train herself. Palla got her licence last year.