A key detail in last Sunday’s municipal elections in North Rhine-Westphalia is likely to attract more attention going forward. It has nothing to do with the outcome: the Christian Democrats suffered minor losses; the Social Democrats saw their worst results ever in former strongholds; the Greens took an anticipated blow; and the AfD nearly tripled their vote from 5.7% in 2020.

What will draw increasing scrutiny, however, isn’t just who got elected – but who wasn’t allowed to run.

Take Uwe Detert. The AfD councillor from the 35,000-strong town of Lage has a remarkable social media feed: “The German Reich is here – it never fell”, he writes on it. And: “Germany is not a sovereign state.” Or, alongside a pic of a teenage Angela Merkel: “Chosen by the Rothschilds as a teenager, moulded and brought to power!” When the AfD nominated Detert as mayoral candidate, a few alarm bells rang. Loudly.

Membership of an extremist party – as the AfD is currently classified, pending judicial review – already casts doubts on a nominee’s eligibility as mayor. Despite this, in three cities, Gelsenkirchen and Duisburg among them, far right candidates will be in the run-offs at the end of September.

In Lage, the election officer sought information from the Verfassungsschutz, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency. Their report arrived just before the committee meeting. It included further posts from the 60-year-old plumbing contractor – calling Roma and Sinti people “rabble” and exaggerating Dresden air raid casualties with forged Nazi documents circulated by Holocaust deniers. The official conclusion: Detert is a right wing extremist.

And that matters. Unlike councillors or MPs, mayors aren’t elected representatives – they are elected civil servants. So an enemy of the constitutional order cannot be allowed to head a city administration.

There’s legitimate concern, though, that banning the AfD’s candidates – who often don’t stand a chance of winning (yet) – risks turning them into martyrs, granting the far right the attention they crave.

Then there’s a logistical risk: if a ban is overturned in court, the entire election must be repeated. This could energise far right voters while leaving moderate ones at home the second time around.

In Lage, finally, six committee members voted in favour of exclusion – enough to remove Detert from the race. The AfD called the decision a “direct attack on democracy and the will of the people!”

Just 30 miles south, another election committee reached a different conclusion. In the diocesan town of Paderborn, the AfD’s candidate, Marvin Weber, remained on the ballot – despite the Verfassungsschutz seeing indications that he too opposes the democratic order.

The 29-year-old student calls Germany an “all-party apparatus of repression” and a “shabby West GDR”. He claims that the government is controlled by “US governors” and regularly describes migrants as “welfare tourists”, “invaders” and “knife jugglers”.

Suggested Reading

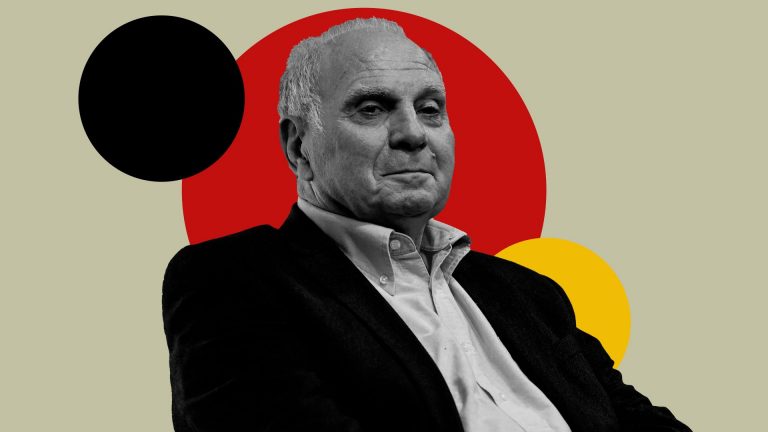

Uli Hoeneß and the summer’s record-breaking transfer frenzy

Still, the committee, with five votes to two, allowed him to run, thereby rubber-stamping him as loyal to the constitution.

The deliberations in Paderborn were similar to those in Lage. The fear of legal reversal prevailed, though, with Weber insisting he was well within “the scope of freedom of expression.” On Sunday, he came third with 14.7% of the vote.

He will probably be forgotten soon, but cases like his will continue to surface. A few weeks ago, an AfD nominee was banned from running as mayor in Ludwigshafen. Next spring, there are municipal elections in Bavaria and Hesse.

The ever-growing concern about the rise of the far right is now accompanied by worries that the current system of vetting and, if necessary, excluding candidates is inadequate.

Election committees consist of only a few council members, working in an honorary capacity, not legal scholars. They must assess complex constitutional questions under tight deadlines before ballots are printed – with sometimes just a few hours to review intelligence reports.

Also, legal oversight ahead of the election is limited to a check for obvious bias or technical faults.

This leaves committees with enormous discretion, little guidance and even less time. Given the constitutional right to stand for election, the current procedure could undermine both legitimacy and public trust, as committees are accused of eliminating competition. Earlier court involvement could ensure certainty, and automatic screening of nominees could help, but would require more resources.

Until reform, debates over what were routine meetings will intensify. Old routines have to go when the political temperature rises.