As Paris swelters in an intense heatwave, tourists and locals take refuge in the shaded terraces, sipping cold drinks and seeking relief from the sun. I pass by and head towards a modest tent set up in the corner of Place de la Sorbonne, where Iranian flags flutter in the rare gusts of wind. There, I meet Hamid Assadollahi, a member of the Committee to Support Human Rights in Iran, founded in December 2004 by victims of the Iranian regime. Hamid has spent the afternoon speaking to passers-by, explaining the ongoing resistance of his people to one of the bloodiest regimes in the world.

Since the ceasefire was declared following the 12-day war with Israel in June, fewer people have stopped by to chat, Hamid says. As soon as Iran fades from the headlines, public interest dissipates. What hasn’t faded, however, is the repression inside Iran. That has intensified. Since Israel’s offensive began on June 13, more than 700 people have been arrested inside Iran, and six executed for espionage. Activists fear this is just the beginning.

Hamid gestures to a large poster displaying the faces of prisoners on death row.

“This man was executed three weeks ago,” he says. “And at any moment, anyone else on this board could be killed the same way.”

He believes the ceasefire is no reason to turn attention away from Iran. The opposite: the war, he says, has exacerbated the pressures on Iranian civilians, making this a critical moment for a population now suffering worse repression than ever.

Hamid cites the 1988 massacre ordered by Ayatollah Khomeini, in which thousands of political prisoners, primarily sympathisers of the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, were executed following the end of the war with Iraq.

“When Khomeini accepted the ceasefire with Iraq, he ordered the massacre because he was afraid of a popular uprising,” Hamid says. “And today, the regime, feeling weakened, could very well use this war as a pretext to settle scores with the resistance.”

The National Council of Resistance of Iran, a coalition of opposition groups, has reported on deteriorating conditions in Iranian prisons. According to the council, on June 23, after a missile strike on the notorious Evin Prison, authorities violently transferred all inmates, most of them political prisoners, to three other facilities known for their dire conditions, lack of space and basic commodities.

Suggested Reading

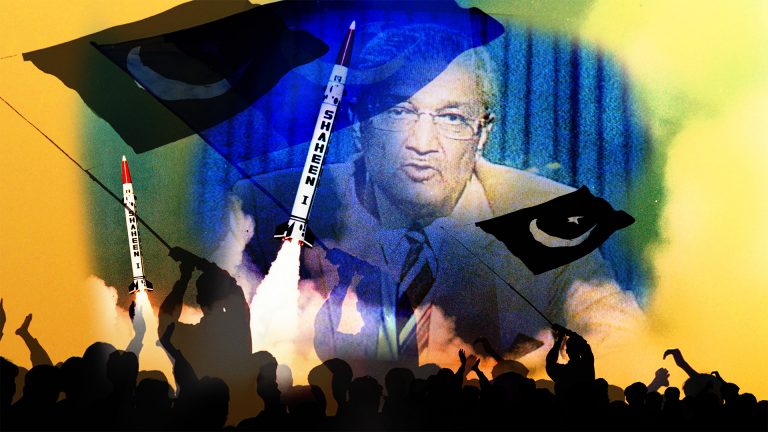

The father of Iran’s nuclear programme

Zolal Habibi, of the resistance council’s foreign affairs committee, says that at Dizel Abad Prison in Kermanshah, guards opened fire on prisoners trying to move away from a potential explosion following a strike on a nearby military base. The incident reportedly left 10 dead and 30 wounded.

“Instead of setting up shelters for civilians, the regime increased its security presence in cities to prevent protests from an outraged population blaming the regime for the war,” Habibi says. “Iran is facing a new wave of repression, with hundreds arrested on fabricated political and security charges.”

Although some Iranians initially reacted with relief at the deaths of key figures in the regime’s repression apparatus, Ali, a human rights volunteer, believes most Iranians understand that a foreign war is not a path to regime change. There is a danger that the situation will worsen for ordinary people. The government, he says, is already beginning to exploit emergency wartime powers.

Ali has suffered under these powers before. He lived through a detention in 1981 at just two years old. The authorities used him as leverage against his parents, both members of the resistance.

Both Hamid and Ali say the only path to a democratic Iran lies in the international community abandoning its policy of complacency towards Iran’s government. There must be regime change, but independently, without foreign intervention.

“A crucial first step,” Hamid notes, “would be for the European Union to officially designate the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organization.”

“At present,” he says, “international appeasement has been one of the main obstacles to regime change.”

Svetlana Lazareva is an independent multilingual journalist based in Paris