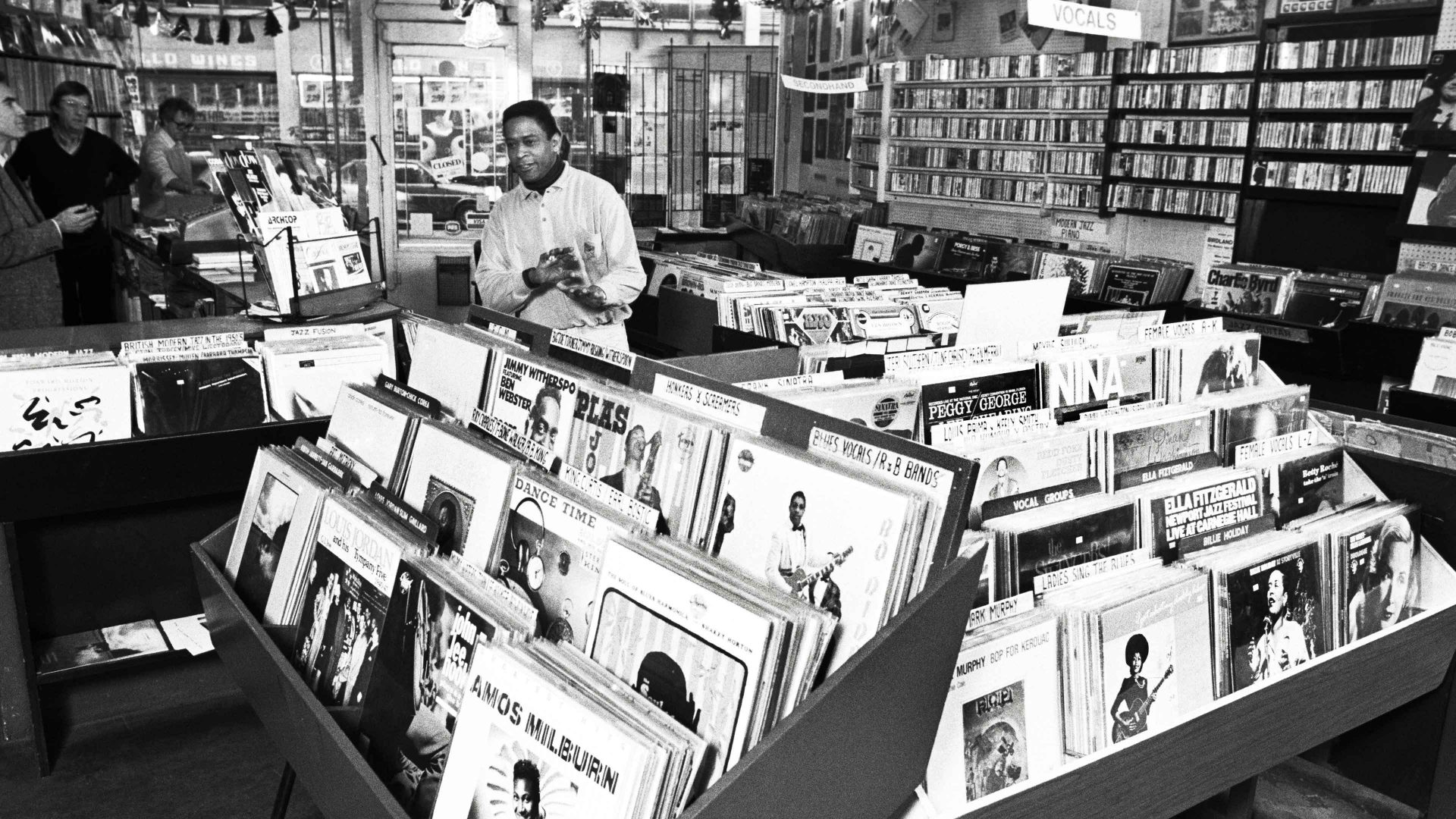

The boom in vinyl (never “vinyls”) continues to surprise music business insiders, whose money-making model is now built on music streaming and a singles-based sound file culture. It also presents challenges for something else supposedly belonging to the past but which is experiencing its own resurgence – jazz.

Originally driven by a buoyant second-hand market for 12-inch vinyl LPs, the “new” vinyl sector entered the market around 2006. Sales were initially tentative, reaching one million in the US by 2007. Yet by 2015, sales hit 11.9 million, defying all expectations. By 2020, they had reached 27.5 million.

Despite regular predictions that year-on-year growth would plateau or even fall back – and yes, they faltered during the pandemic – by last year, US vinyl sales were 43.6 million, higher than when the LP was replaced by the CD in the 1980s. In Britain, 6.7 million vinyl records were sold in 2025, a 30-year high.

Ownership of vinyl presupposes a different relationship to music than digital, where experts tell us a significant portion of skips occur within the first five seconds of a song, with mobile listening typically having a higher skip rate (51.1%) than desktop (40.1%).

In contrast, albums are intended to be listened to from beginning to end with just one flip in the middle. While CDs, downloaded music files and streaming may end in silence, the regular click when the pickup-head reaches the central groove when one side of a record has played through is a nagging call to action – get up, turn me over or choose something else.

The album is a track-by-track experience. A smart producer will arrange each track so the music forms a narrative arc that begins on side one and ends on side two. In the best soap opera tradition, each track leads into the next to keep the listener hooked. The boss and producer of ECM Records, Manfred Eicher, resisted putting his label, home to countless classic jazz LPs, on a streaming platform for years as he felt cherry-picking certain tracks would destroy the narrative arc of the ECM album experience.

Another key aspect of a 12-inch LP was the status that cover art came to assume. The iconic cover art of Dark Side of the Moon, Sgt Pepper’s and London Calling in pop, or Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, Oliver Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth and Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew in jazz, were all lost with the arrival of the MP3 and streaming culture.

Suggested Reading

Why Japan fell in love with jazz

ECM was not alone in putting enormous effort into ensuring the visual was an aesthetic entry point into the aural, something that was missed with digital and has been a factor in the return of vinyl – some fans even buy the LP as a collectable artefact because of the cover art without the means to play the record inside.

As more and more vinyl reissues of jazz classics, usually from the 1950s and 60s, came on to the market on specialist reissue labels, the sound seemed a vast improvement on the clicks and pops the originals had acquired over the years. Original session master tapes were used to cut lacquers, the LPs were pressed on pure 180-gram vinyl and sleeved in a facsimile album cover, and unselfconsciously priced at around £30 to £50 each. There was no shortage of takers.

With so many releases, both new and reissues, jazz consumers were confronted with the paradox of plenty, with many ending up opting for familiar names: reissues of jazz icons like John Coltrane or Bill Evans. These recordings – originally made around 70 years ago – could withstand repeated listening, and as a result, the music seemed to assume greater meaning.

It means today’s jazz musicians are engaged in the unequal task of battling the past. Some opt for making “their” version of an acclaimed classic, or to play the music of a deceased icon “in tribute.” Experimentation continues, but often the theatrical is mistaken for originality. Few new releases are talked about a couple of weeks or even a couple of months after release, let alone seem destined to last beyond an artist’s lifetime.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is an uneasy feeling that all innovation is done and that the greatest performances are already behind us. In the recording business at least, it seems that the past is now more important than the present – just as happened in classical music, opera and rock.

British writer Stuart Nicholson’s eight books on jazz include Is Jazz Dead (Or Has It Moved to a New Address?) (2005)