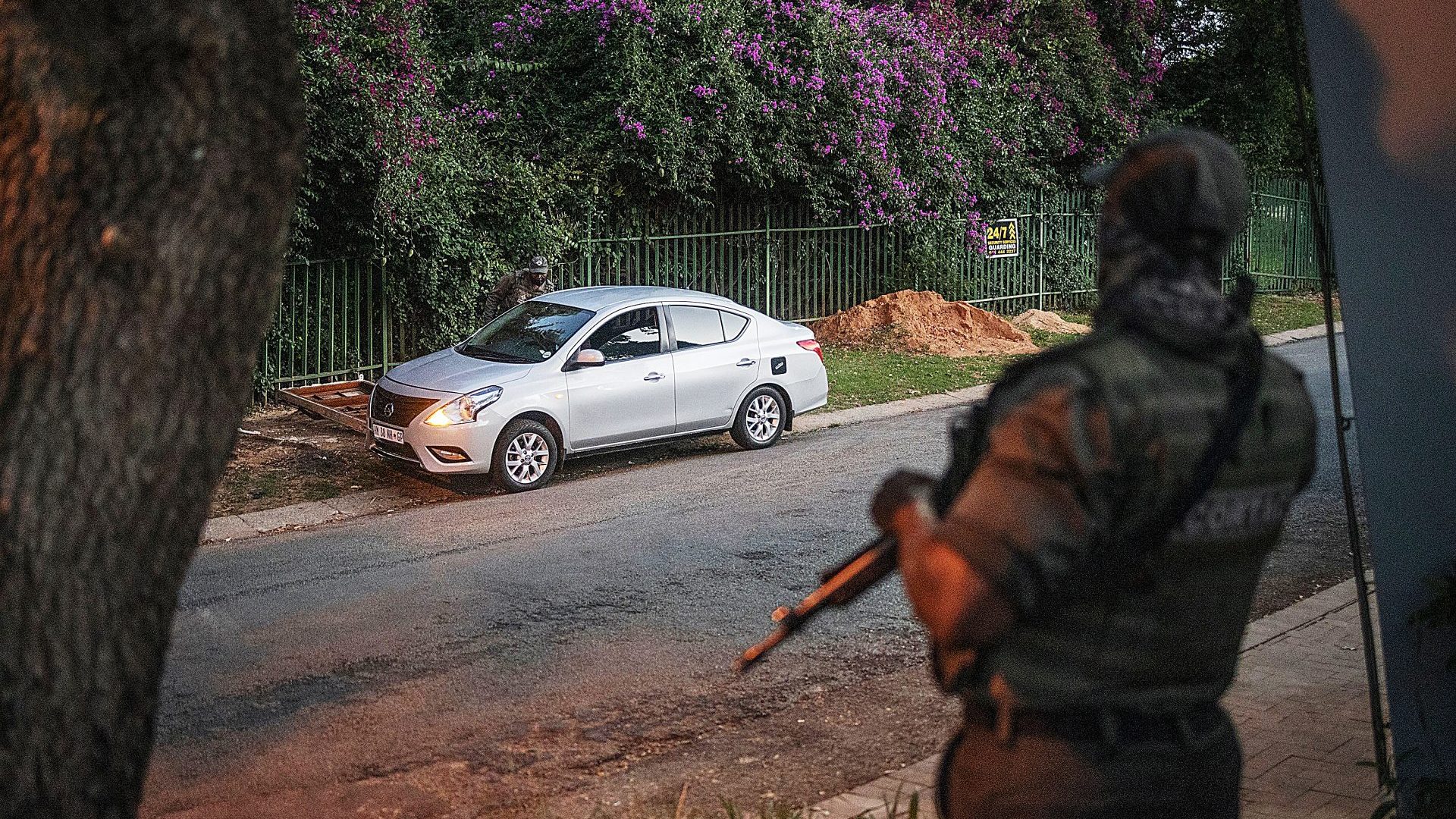

The phone rings late at night – rarely a good sign. My trip to the mountains to cross “the world’s longest suspension footbridge” is off. The government has just closed all the roads into the region as firefighters grapple with the inferno that has raged through Portugal and Spain all summer.

In the cafes of Porto next day, early-risers knock back their cups of strong espresso, like thimbles of gunpowder, and remark that at last the president and prime minister are doing their jobs. They were both awol on their holidays when the summer heatwave first burst into flames back in July.

The authorities now have a further disaster to contend with, after a funicular carriage in Lisbon crashed last Wednesday, killing 16 people.

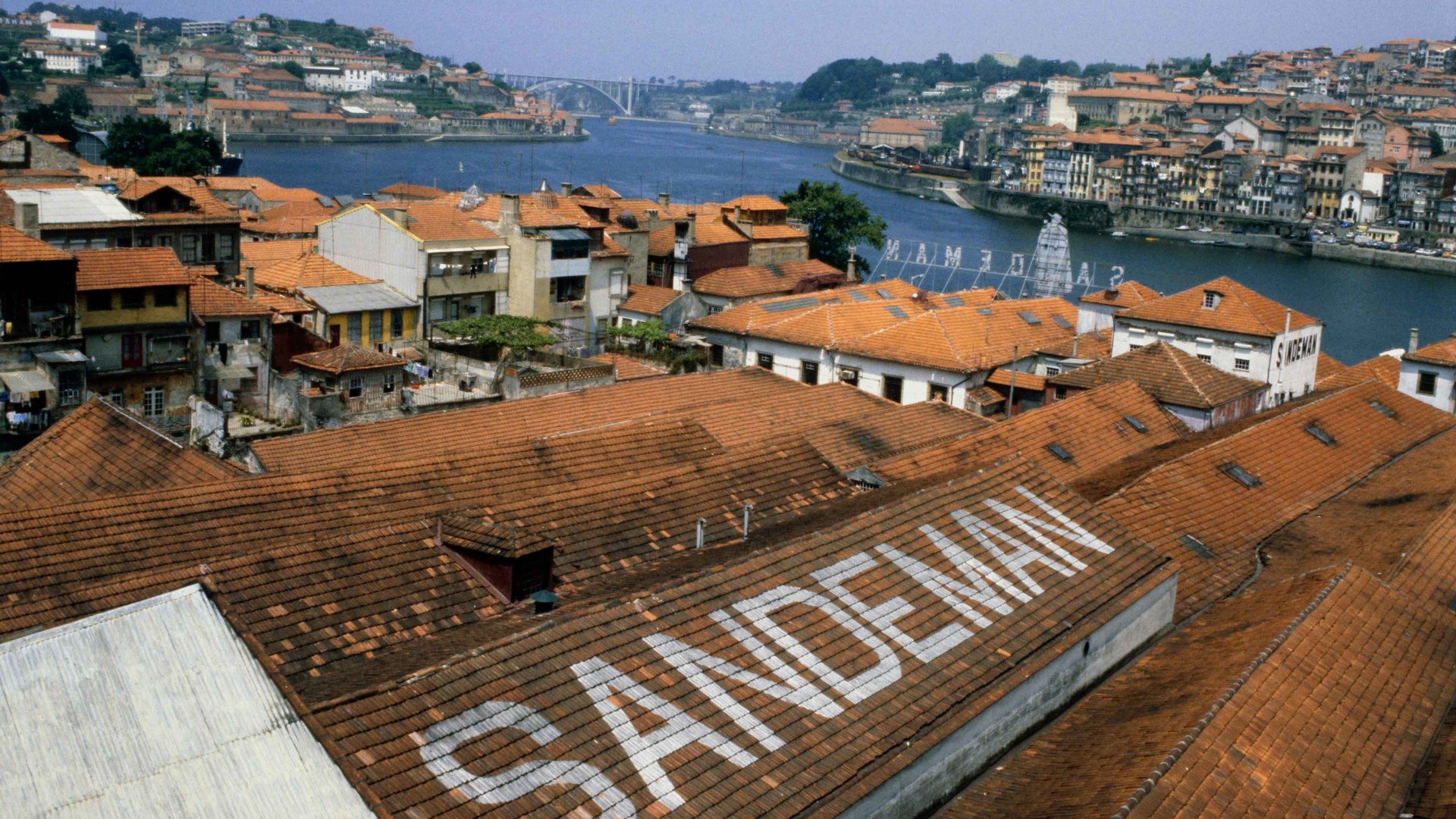

But with my excursion postponed indefinitely, there’s nothing for it but to make other arrangements. A tour of the venerable Sandeman port cellars, in a red-tiled former convent in Gaia across the Douro River from Porto, could hardly be further from the sweltering hand-to-hand combat of wildfires. Or so you would think.

After the fires have tragically consumed lives, terrified communities and destroyed many hectares of valuable land, the fate of a sweet digestif might seem like small beer. But the port industry makes a healthy contribution to the Portuguese economy – more than £300m in 2023 – and it provides work for many thousands of Portuguese, directly or otherwise.

At first, the cool and crepuscular Sandeman vaults, steeped in the bouquet of my mum and dad’s old drinks cupboard, are indeed a respite from the pitiless sun and alarming headlines. But beneath the perfume of fructifying grape, you can just make out the smoky bass notes of port’s origins in the heat and buckshot of battle. Old man Sandeman got into the fortified wine racket in the 18th century when England and France were at war. The British slapped Trump-style tariffs on delicious French grog, so wine merchants like Sandeman turned to Portugal, with whom relations were more cordial.

The bountiful vineyards overlooking the Douro made fortunes for their Anglo speculators. It was the Silicon Valley of its day, with the red stuff lubricating the salons and drawing rooms of fashionable Europe, supercharging the flow of information from one flushed toper to the next. In what proved to be a marketing masterstroke, Sandeman commissioned Scottish artist George Massiot Brown to design its striking logo: an enigmatic figure in a black cape and sombrero (representing the gowns worn by Portuguese students, and Iberian sunshine, respectively).

Suggested Reading

Amália Rodrigues, the voice of fado and the soul of Portugal

This figure, one of the first mega-brands, will celebrate his centenary in 2028. In a further promotional coup, the firm enlisted a down-on-his-luck Orson Welles to bring the figurehead to life in TV commercials. “Sandeman, it’s the one,” growled the great man, between generous swigs of the product when the cameras weren’t rolling. “We will sell no wine before its time,” added Welles, in an earnest statement of Sandeman’s respect for the dignity of the cellar, where vintages are laid down for 100 years or more, like the bones of Porto’s eminent cadavers in the nearby catacombs of São Francisco church. The man in black is still on the bottles, and outsize images of him loom over Gaia alongside the proud blazons of the London merchants who were the Elon Musks and Jeff Bezoses of 200 years ago: Dow, Graham, Turner and more.

Sandeman’s man in black is known as The Don. Unlike his namesake in the White House, the Don is not a climate-change denier. A spokesman for the company told me: “We are watching anxiously to see what happens with these fires. We have seen blazes encroach on the port estates in recent years and the harvests suffer.”

Wildfires have gobbled up vines, and even the grapes that are spared by the flames are tainted by smoke, affecting quality and taste. The proximity of the advancing firewall means workers down tools and flee the hillside terraces, interrupting the grape-growing calendar. Sandeman and other firms are introducing firebreaks into the wine estates and planting fire-resistant trees.

They employ nanotechnology and AI to monitor the health of their crops remotely. Sandeman has rearranged its schedule for picking the grapes. This once happened every September, as surely as the sun coming up, but has now come forward to August or even late July. The firm will doubtless continue to honour Welles’s pledge: it wouldn’t dream of selling a wine until it had matured into a mellow accompaniment to cheese and nuts. But outside the gloom of the Sandeman grotto, the timetable of viticulture, as well as much else, is increasingly subject to violent interruption reminiscent of Welles’s famously terrifying radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds.

Stephen Smith is a journalist and broadcaster