Sasha’s children, if she has them, won’t speak Russian. “Because fuck that,” she told me over coffee near Odesa’s European Square.

It was called Katerynska Square when I first visited Ukraine’s third city in June 2022, and Catherine The Great’s statue still stared, with steely pride, over the heads of her former subjects. It bore a tiny Ukrainian flag then, but later someone replaced it with a noose. Three years on, the Russian empress and her entourage have long since been removed.

Odesa is especially beautiful in the summer, with its roses in full bloom and seemingly infinite stretches of sand where the city melts into the Black Sea. Now in her early twenties, Sasha was born here. Her mother and father are Ukrainian and Belarusian respectively, yet she grew up speaking Russian and listening to teachers extol the virtues of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky.

The reasons for this, Sasha explained, go back hundreds of years. Under the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, Russian was the language of administration, industry, and culture, while Ukrainian was stigmatised as a peasant language.

Catherine II, the Russian empress now confined to a museum, is credited with founding Odesa in 1794 despite historical evidence that human settlement here stretches back to antiquity. Until recently, one of Odesa’s arterial streets was named after the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, even though he only spent 13 months here in exile in the 1820s. It’s now known as Italiiska, or Italian Street. (Though Pushkin described Odesa winningly as a lively European city, he is ubiquitous in Russian propaganda. During the brutal nine-month occupation of nearby Kherson, his face was plastered across billboards proclaiming that the city would be “Russia forever.”)

In 2014, Ukraine ousted its pro-Russian president and Russian tanks rolled into Crimea and Donbas. Coming of age in the shadow of this war, Sasha began to unpick the national myths she’d grown up with. Years later, she’s still discovering new Ukrainian artists and writers whose work was once suppressed – Ivan Bahrianyi, who survived two Soviet prison camps, is her latest read. His descriptions of Ukrainians suffering at both Nazi and Soviet hands affected her deeply. “I was brought up to believe that the Soviet Army saved the world.”

Kremlin propagandists refer to great swathes of territory where Russian is widely spoken, all the way from Odesa in the far southwest to Kharkiv in the far northeast, as Novorossiya, or New Russia. “Odessa is a Russian city. We know this. Everyone knows this,” Vladimir Putin claimed in 2023.

Suggested Reading

‘Russia is the enemy, not queer people’

For Sasha, who grew up bilingual, the idea that Ukraine can be neatly divided into Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking areas is an obvious lie. Nor need you look far for proof that the city is not inherently Russian.

Old ladies bus in from the surrounding villages to sell fresh eggs and herbs at Odesa’s markets. “They’re not coming from Lviv [far-western Ukraine] but they speak Ukrainian,” said Sasha sardonically. “In any region of Ukraine, you’ll find people who still speak Ukrainian, because it survived in the villages. The smaller the village is, the more likely it is to be Ukrainian-speaking.”

The young seem to bear this burden of history more heavily than their parents, many of whom are staunchly pro-Ukraine but view Russian aggression as separate from culture and language — Putin’s war. Sasha is frustrated by this. “For centuries, we’ve been fighting the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. And I don’t think whoever comes after him will be much better.”

One day she might revisit Dostoyevsky, but first he and other Russian writers need to give way to the Ukrainian ones his empire suppressed. “I just feel like it would be healthy for Ukraine to think there’s no such thing as good Russians for a while.”

“Odesa is a bubble,” said Artem, lighting the stove. He’s in his thirties, with dark hair and eyes and a wry sense of humour. He’s Russian, so when we meet, we speak in French – though I struggle to keep up with his effortless fluency.

At the time of the full-scale invasion, he’d been living in Odesa for three years. “We understood nothing; we thought that the Russians would take the city in two days.”

Nevertheless, he cut up his Russian passport and posted photographs online for the world to see. Then he applied for asylum. Now he shares a tiny flat with nine cats just outside the city centre — a tenth, belonging to his neighbour, meowed loudly throughout our conversation. “I wouldn’t say it’s too sensitive a subject,” he said over the sound of her indignation. “People speak whatever language they want to here.”

To Artem, arguing over monuments and street names is a distraction. Efforts to phase out the Russian language trouble him (what of the thousands of Russian-speaking Ukrainian soldiers fighting at the front?) but have never caused conflict with those who now choose to speak only Ukrainian. “It creates pressure, but never goes so far as to make a war between you. We already have a war.”

I once asked him if it was hard to destroy his Russian passport – we both knew that, had Odesa fallen, this act of defiance would have put him in danger. But no, he replied. “I felt in accord with myself.”

Suggested Reading

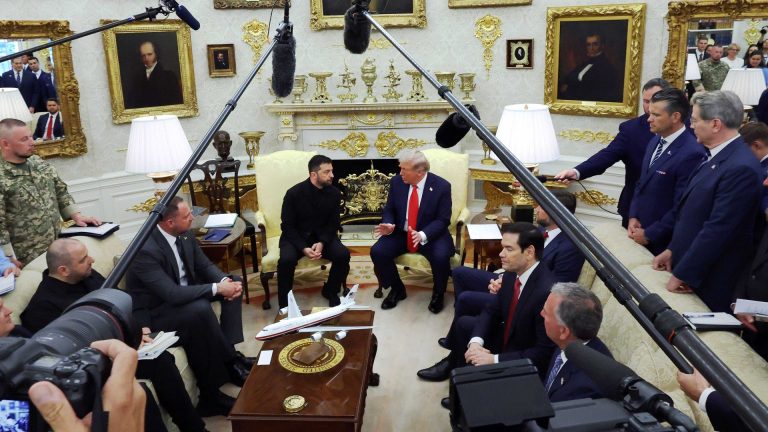

Why Trump can’t end the Ukraine war

Now he’s just tired. “I felt nothing,” he said when I asked him about the latest peace talks in Washington and Alaska, echoing the sentiments of every Ukrainian I spoke to. Without a passport – even a Russian one – he can’t legally work, marry, or even, he jokes, die. The Ukrainian government denied his first asylum request, a decision he is appealing.

“According to them, I can return to Russia without any problems, say hello at the border and live in peace.” Artem, like Sasha, rejects the claim of Russian propagandists that speaking Russian makes you Russian, though he has responded to it differently.

“If someone told you that drinking coffee in the morning made you a donkey, would you stop?” he asked, casting about for a metaphor. “Just because they say it, doesn’t mean it’s true.”