The sun was rising, and my stepfather and I stood beside a battered pickup truck on a small road winding up into the French Pyrenées. “On va se promener un peu,” François told me happily. We’re going for a little stroll. I knew him well enough to find this statement highly ominous.

As wiry and sure-footed as a mouflon, a wild ram, François is in his sixties. The sun had yet to arrive above the surrounding peaks, so he and I and the secret world of forest creatures were still cast in shadow. I could almost feel their hearts beating in the undergrowth around us. I was acutely aware, too, that thirty armed men (and one armed woman) were assembling. Old men, most of them – one of them helped to his post with an oxygen tank in tow – in place of the jeeps and helicopters which would otherwise be sent by the government to conduct a cull.

Suggested Reading

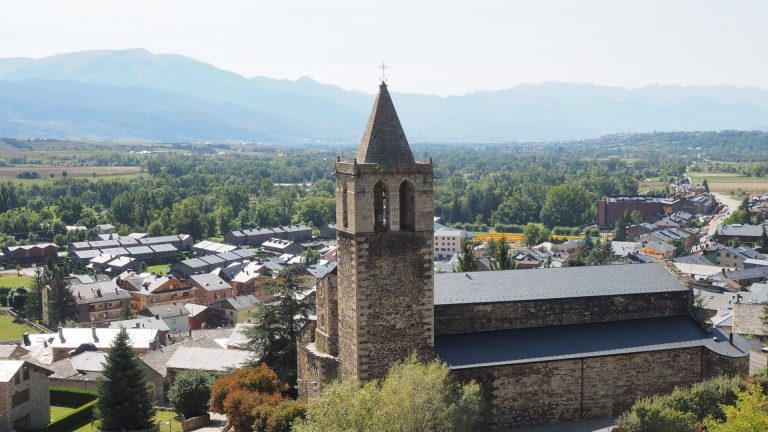

Visiting Spain – but in France

While we waited for confirmation that everyone was in position, François turned the car around so we could roll it back down the steep road to the village if necessary – the battery was on the blink. In the back, six terriers wearing fluorescent Kevlar vests trembled with excitement. They ignored my overtures, entirely focused on the sounds and smells of the mountain, so I went to stand at the lip of the steep, overgrown path I assumed we’d take into the forest. When the radio finally crackled into life, however, François simply shouted – “Allez!” – and leapt from the road into a ravine full of brambles. Swearing, I changed course and hurtled after him.

Before I knew François, the word hunter would have conjured up images of foxes being torn apart by dogs and tweedy aristocrats galloping through rolling fields. François is retired now, but it’s hard to imagine a life further removed from monied leisure. He left school to become a miner, nearly half a century ago. The pit closed a few years later, and he became a woodsman – helping carve out the agricultural terraces that make it possible to grow grapevines and other crops on the near-vertical slopes of this wild country. The local factory soon folded too (its hulking, rusted ruin still looms over the village) and the village shrank to nothing overnight. It’s a sleepy place now, with a shop, a bakery, and a café-bar where the old men sit drinking Ricard and playing cards. Forty years ago, he tells me, there were at least six cafés, a cinema, and a nightclub.

François is a piqueur, meaning that his role in the hunt is to run with the dogs as they flush wild boar out of their hiding places and into the path of the hunters’ guns. To be good at this, you have to forget a fundamental law of walking in the Pyrenées, which is that what comes down must go up — crashing down the rocky incline for hundreds of metres with no regard for the fact that you will have to sprint back up again moments later. And François is very good. Within an hour, my lungs were screaming in protest, I’d narrowly avoided twisting an ankle, and only the desire to avoid a second humiliating “Ça va, Sophie?” kept me trailing after him. From time to time, he stopped dead in his tracks, listening, on a still mountainside turned to molten gold by the dawn.

“Ouilé, ouilé!” cried François fiercely, shattering the silence. Where is he, where is he! And the dogs were off again, noses to the ground as they scrambled through bushes and up treacherous ravines. Until one of them found “him,” or his scent at least — alerting us with a high-pitched, pained sound, not quite a bark. An adult wild boar can weigh over 100kg, with tusks that can tear a stomach open like tissue paper, and your only warning of its arrival is the sound of breaking branches as it crashes down the slope towards you. I lurched to the right, clinging to a tree to avoid putting myself in this one’s path, and was temporarily deafened by the sound of François discharging his rifle.

The smell of smoke, and then blood. Gravity dragged the boar onwards even as he died, until his body tumbled to a halt at the bottom of a ravine. We approached cautiously, as wounded boar are at their most dangerous. He looked small in death, his slackened mouth open.

François took out his hunting knife and went to empty the body of its innards – a dark cloud of vultures would soon amass above this spot, the parts of the boar that humans would not use going to feed the other creatures of the mountain. My stepfather has never missed a hunting season, apart from the year he was going through chemotherapy. Later, at the village lodge, the hunters would fire up the decrepit coffee machine and break open bottles of cheap whiskey, reliving the day’s work as they butchered and divided up the meat to fill each other’s freezers. But killing is never easy. For one moment, as the smoke dispersed, the mountain was quiet.