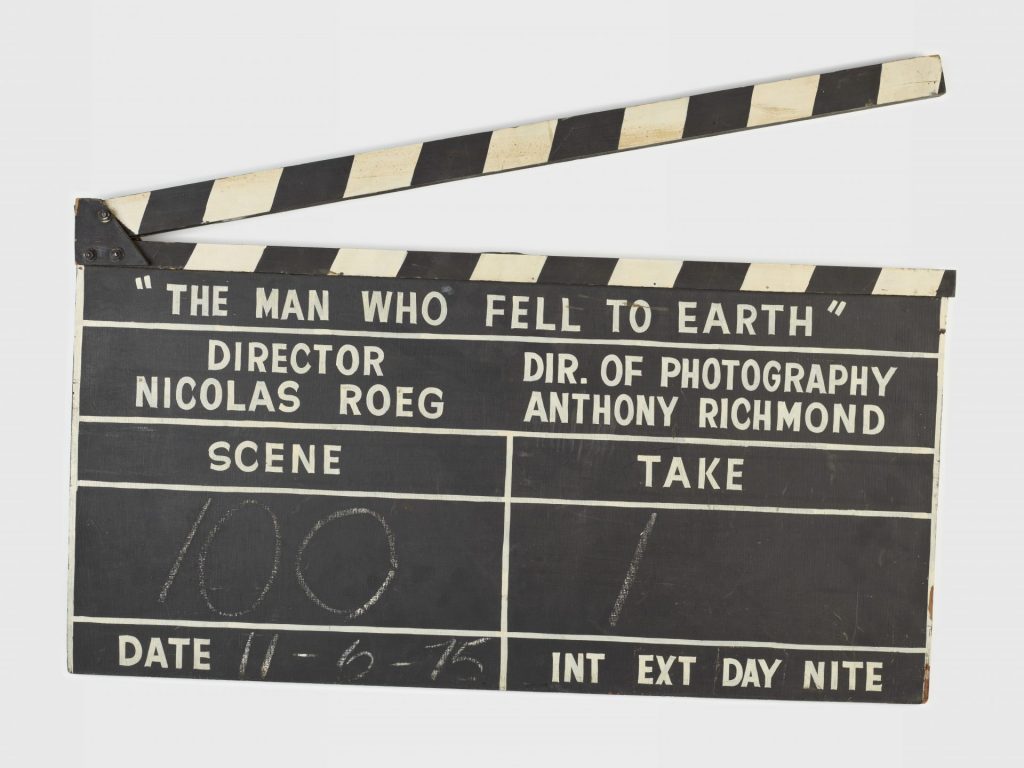

I’m staring at the chewing gum on the soles of David Bowie’s shoes and wondering why I’m finding it quite so thrilling. The David Bowie Centre, which opened on September 13 at the V&A East Storehouse, is the new permanent home of the rock icon’s 90,000-object personal archive, and it was via the groundbreaking Order an Object service, a facility open to all, that I found myself holding the size 42 black leather footwear in my purple nitrile-gloved hands.

A poster of Bowie wearing the outfit the shoes belong to – the “Thin White Duke”, as seen on his 1976 Isolar Tour – once hung on my teenage bedroom wall. This was quite exciting enough, but the discovery of that 50-year-old gum – an absurdly humdrum detail – seemed to open a portal to a time before I was born.

London’s love affair with popular music in its cultural spaces is in full swing. Right now in the capital you can see Kurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar and cigarette burn-covered cardigan from Nirvana’s 1994 MTV Unplugged performance (Royal College of Music Museum), tour Jimi Hendrix’s London haunts, starting from his Mayfair flat (Handel Hendrix House), and discover artefacts from the Blitz, “the club that shaped the 80s” (The Design Museum).

The David Bowie Centre is the latest and most spectacular in this trend, but it raises key questions about the relationship between audiences and cultural institutions and how we seek contact with stars through the objects associated with them.

The V&A East Storehouse, which opened in May, is mind-melting. Designed by Diller Scofidio+Renfro, the vast metal catwalk-lined atrium, where all four storeys can be seen at once via a vertigo-inducing glass floor, is architecture as full sensory experience.

As this is a working warehouse, most objects are packed away on the shelving, but the selection facing into the central space make for a kaleidoscope of juxtapositions across space and time – a Chopper bike next to a carved medieval altarpiece, a pair of 19th-century Japanese Imari vases next to a 1930s wood and steel chair by Marcel Breuer. This is where Ikea meets the Victorian cabinet of curiosities; it well rewards those who have ventured intrepidly into the dystopian, anonymous building site that is the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park to visit it.

Unfortunately, this dramatic space filled with light does the David Bowie Centre itself, confined to a dark corner, no favours. Neither do comparisons to David Bowie Is, the blockbuster exhibition which put items from the David Bowie Archive on display for the first time.

Opening in South Kensington in the summer of 2013, it then toured 11 global locations over the next five years. When Bowie died unexpectedly in January 2016, it turned from a celebration into an epitaph.

While David Bowie Is was an immersive, rock concert-adjacent experience by virtue of wraparound multimedia installations, the David Bowie Centre is very much not that, and neither should it be expected to be. Billed as “a space for research and critical reflection on Bowie’s diverse legacy”, its glass-walled study and reading rooms are meant as its principal spaces.

The area with nine displays from the archive that will change periodically and which is sold out until late October has sombre lighting, floor-to-ceiling locked cabinets of archival material, and just one screen showing music videos at a discreet volume. Where David Bowie Is had a complete aural landscape and a constant sense of movement, the new Centre is static and sedate, and this is appropriate to its mission.

The curatorial approach is more problematic. David Bowie Is started with a quote from Bowie’s 1. Outside album liner notes – “There is no authoritative voice, there are only multiple readings” – but the inaugural displays at the Centre are far keener to tell us what to think. Five decades on from the emergence of the “new museology”, which argued that curators should look to the wider social and cultural contexts of artefacts and make them subject to the visitor and the community rather than the other way round, it seems we are at a place where museum collections can be bent to breaking point to fit an external agenda.

The David Bowie Centre displays were devised in consultation with 18-25-year-olds from the four Olympic Boroughs of Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets and Waltham Forest. Unhappily, curators found that many of them had never heard of Bowie, but they remained undeterred, and V&A East head curator, Madeleine Haddon, has confirmed that “This finding has significantly informed our curatorial approach”.

The effort to engage the young and uninvested is responsible for the very first thing you see at the Centre – a scruffy display of CDs, DVDs, magazines and photographs meant to show the breadth of Bowie’s legacy (the museum ambitiously calls this an ‘interactive installation’). Every big name in pop of the last two decades is here, from Beyoncé to Harry Styles, however loose their connection to Bowie’s body of work.

Bafflingly, there’s also DVDs of children’s film Happy Feet Two and the Friends TV series (Bowie featured, briefly, on the soundtracks, it turns out). This attempt to carve out arguments for Bowie’s cultural significance for a young audience has resulted in something that is both trivialising and inelegant.

The V&A’s wider efforts to “decolonise” a collection built in Britain’s age of empire has also led to an obvious and strenuous attempt to compensate for Bowie being a white male. There is an insistent emphasis on the black artists Bowie worked with: Luther Vandross, Ava Cherry and Robin Clark, the backing singers who gave the Young Americans LP its sound; Nile Rodgers, producer of Let’s Dance and Black Tie White Noise; Goldie and A Guy Called Gerald, collaborators during the 1990s; and a whole vitrine dedicated to Bowie’s long-time bass player, Gail Ann Dorsey.

While some might argue that this is an important reflection of the diversity of the local community, others may call it curatorial shoehorning, and Bowie’s relationship to race was hardly straightforward. Contrast the panel which overreachingly claims that Bowie was “one of the earliest white mainstream artists to engage seriously with Black music”, with Bowie’s own self-reflexive, irony-laced words from 1976: “Young Americans is, I would say, the definitive plastic soul record. It’s the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey”.

Suggested Reading

David Bowie, the Great Curator

Emphasis is put on the Let’s Dance video highlighting the oppression of Aboriginal Australians, but such overt “messaging” was an aberration in Bowie’s career, and the statement that “Bowie used his music, films and videos to critique social issues like homophobia, colonialism, racism and war” gives a wholly false impression of explicit political intent.

As assistant curator of David Bowie Is, Kathryn Johnson, has written, “Bowie gives us a medium rather than a message”, yet here he is co-opted as a crusader for social justice, with all the dull moral certainty that implies. While broadening access and representation is undoubtedly important, the flattening of Bowie’s complex multivalence in its name is more than unfortunate.

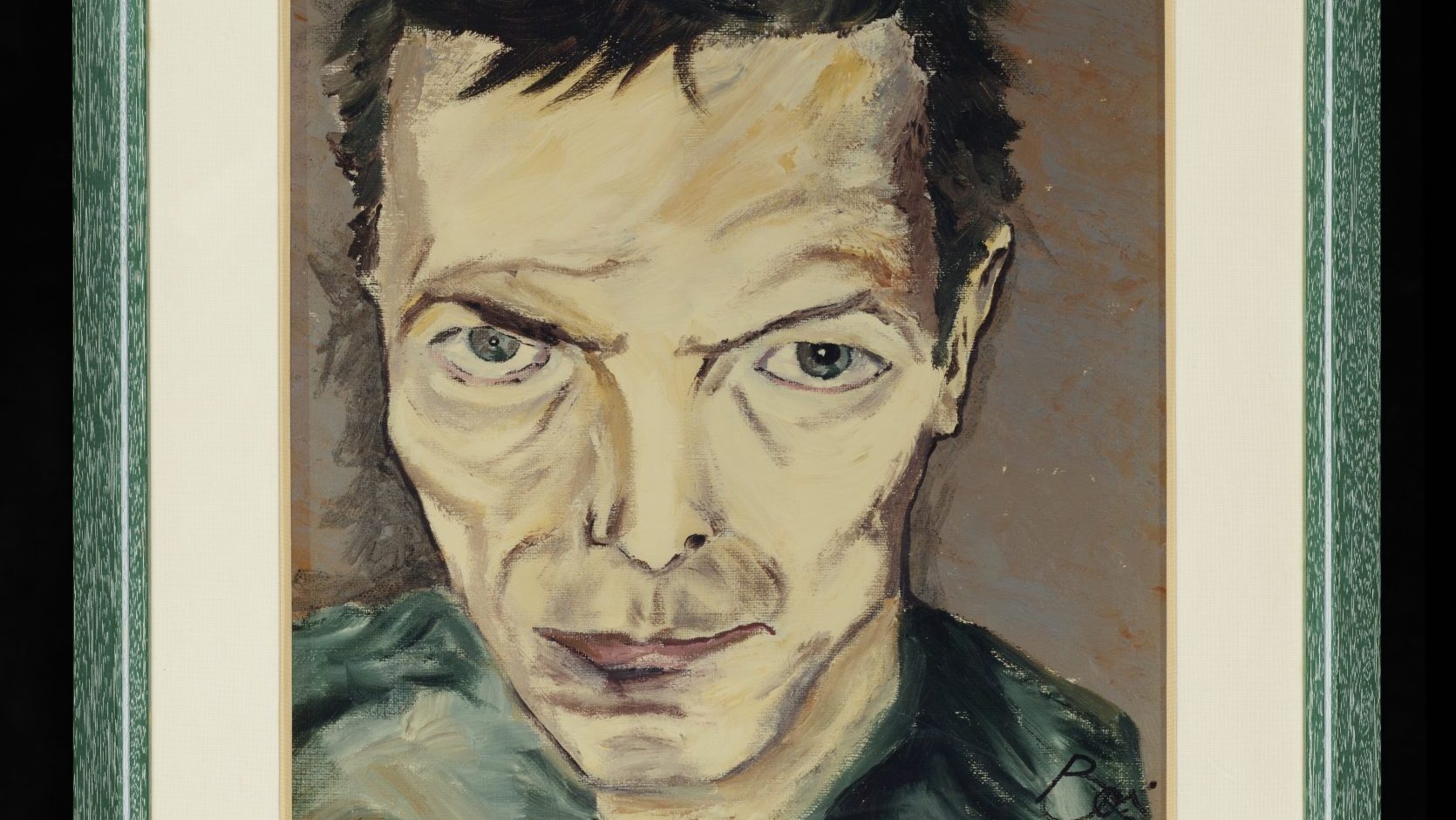

That a pre-conceived message was rarely the point of Bowie’s work, which privileged the creative process above the end result, is proven by the vitrine focusing on unrealised projects. This contains newly discovered material from the Archive and is the undoubted highlight of the displays.

There are notes for “Leon in India,” a performance project with Brian Eno which ultimately morphed into the album 1. Outside. A Staples notebook and hand-written post-it notes dating from Bowie’s final months brainstorm ideas for a musical inspired by the colourful and the grotesque characters of 18th- century London. His originality to the last is definitively proven.

But it is the Order an Object service that makes the David Bowie Centre truly worthwhile. I chose objects spanning four decades – alongside the monochrome Isolar outfit there was the voluminous Ziggy Stardust white silk cape designed by Kansai Yamamoto, the light blue Freddie Burretti suit from Live Aid, and the Vivienne Westwood silver skeleton earring Bowie wore when he received the Outstanding Contribution award at the 1996 Brits. These objects are discovered anew when encountered in person, from the authentic gig grime on the hem of the cape, to the delicate figurative design on the Live Aid tie, and the fine textured raw silk of the Thin White Duke’s waistcoat.

And here perhaps is the key to the soaring popularity of music exhibitions. In an economy of expensive and scarce concert tickets, such displays afford easy access to stars (the V&A’s Taylor Swift Songbook Trail display of costumes supplied a demand the sold-out Eras Tour could not meet), and they hold the promise of new audiences and revenue streams for institutions (David Bowie Is was the fastest-selling exhibition in the V&A’s history).

But in the end, the aura of authenticity – of being in the presence of the real thing – is the real motivator. This drives every visitor to every museum, but when we add to that the sometimes life-defining relationship fans have to their idol, it becomes a genuinely profound experience.

Ultimately, just as the Storehouse strips back the layers of the museum to reveal the bare bones underneath, the David Bowie Centre affords glimpses of the man beneath the star. The fifth object I ordered was the plastic saxophone that was the first musical instrument Bowie ever owned. It was bought for him by his father for Christmas 1961, when Bowie was 14, and it finds its companion piece in a reference letter written by his father, which is on display. “I do not think I could have taken all the setbacks he has taken and come up smiling and still full of confidence and fight,” it reads.

Suddenly, we have come face to face with David Jones, a bright teenager from suburban Bromley with a driving determination to just do something, and a father who had a touching faith in his son. The man underneath the personas, the glitz and the adulation is in fact waiting to be discovered in this corner of an east London warehouse.

The David Bowie Centre is now open at V&A East Storehouse, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, Hackney Wick

Sophia Deboick is a freelance writer who specialises in music and cultural icons