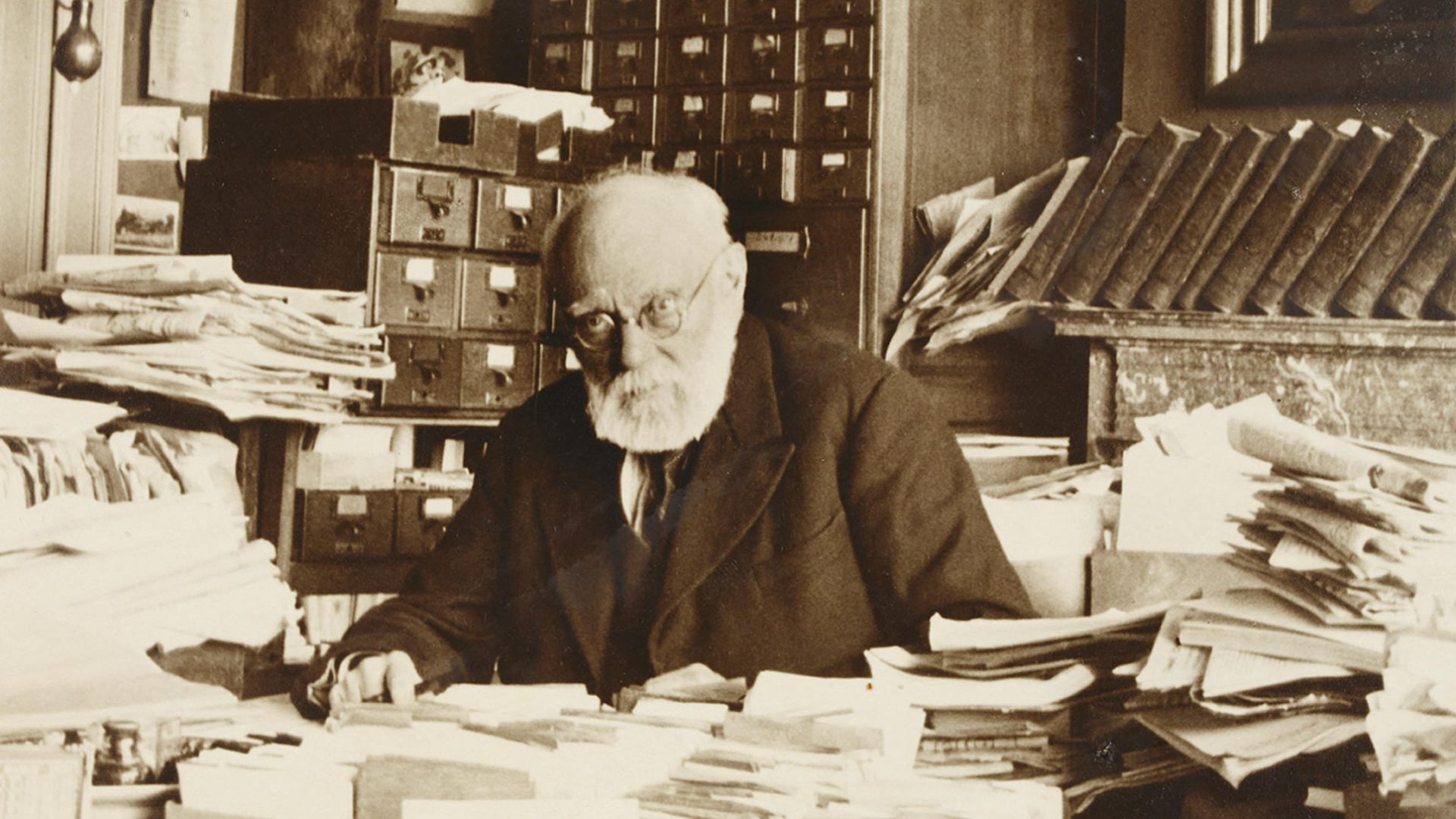

Paul Otlet was walking on a beach with his young grandson sometime in the 1920s when they came across some jellyfish washed up on the shore. Otlet, the very picture of the venerable scholar with his white beard and round glasses, stooped and stacked the creatures in a neat pile.

Then, taking an index card from his jacket pocket, the Belgian wrote “59.33” on it – the code for coelenterates in the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) system that Otlet, an important documentalist of his day, had spent much of the past three decades devising and promoting. He carefully placed the card on the gelatinous pile before sauntering away.

In this one action, the all-consuming passion of Otlet’s life – to catalogue the whole world, literally if necessary – was revealed. His card catalogue that attempted to do just this, the Répertoire Bibliographique Universel (RBU), would eventually consist of more than 15m entries, but Otlet’s projects went far beyond the mere organisation and dissemination of information. Seeing data standardisation as the key to global cooperation, Otlet believed it would usher in world peace and, ultimately, a universal enlightenment that would bring humanity to its most exalted state.

The birth of the World Wide Web saw Otlet, a forgotten figure for decades, rediscovered as a founding father of the internet, since his vision for a global communications system with endless possibilities for the searching and cross-referencing of information seemed to have uncannily foreseen it.

But today, as the private enterprises that control so much of our information have an ever-increasing influence on our thought and, therefore, the direction the world is going in, Otlet’s utopian dream of a world both unified and healed by the free flow of information seems more relevant than ever.

Paul Otlet was a true product of his time and place. It was an era when technology was advancing at a staggering pace, and his father – a member of the Belgian Senate in the years when Leopold II was making Belgium an industrial powerhouse – had made his fortune in trams.

When the latest developments in the telephone hit the news in 1885, the 17-year-old Otlet wrote in his diary, with characteristic reserve, “it is an admirable invention”, and it, along with the innovations that came in a flood in the following decades, would feed his dreams of a world connected through communications technology.

But Otlet’s first and enduring love was information classification. Charged with running the library at the Brussels Jesuit College he had attended as a teenager, he had already devised a system for the organisation of his personal library, and his passion for organising knowledge was only rivalled by a thirst for that knowledge itself. Underpinning this was Auguste Comte’s philosophy of positivism and the pre-eminence of scientific inquiry and empirically observable facts. Comte’s belief in the inevitable upward march of civilisation also informed Otlet’s eternal optimism about the future prospects of humanity.

Yet by his early 20s, Otlet was mired in a humdrum life that hardly reflected these lofty ideals. The family fortune lost in bad investments, and married with young sons, Otlet needed a steady job and went into the legal profession, but quickly abandoned it (“The Bar, what misery!” he wrote in his diary). He was at a crossroads.

At this crucial moment of transition, Otlet met a kindred spirit. Henri La Fontaine was an international lawyer, campaigner for peace (he would win the Nobel peace prize in 1913), Socialist senator and fellow bibliophile.

The two began a lifelong partnership after their 1891 meeting, and the following year Otlet laid out for the first time his vision for how the humble index card could be used to liberate the world’s information from between the covers of books, boil it down to facts, and make it infinitely searchable.

1895 was a key year. Otlet and La Fontaine began building their card catalogue, envisaged, with wild ambition, as “an inventory of all that has been written at all times, in all languages, and on all subjects”.

They discovered the Dewey Decimal Classification system, finding its “nomenclature for human knowledge, fixed, universal, and able to be expressed in an international language – that of numbers” revolutionary. With Dewey’s permission, they began expanding it into the UDC, a system that is still in use all over the world today.

That same year, Otlet and La Fontaine established premises, later to become their “Palais Mondial” – a collection of printed material of huge scope, from ephemera to massive tomes, conceived of as a repository for the world’s knowledge – and founded their Institut International de Bibliographie (IIB), a membership organisation which they hoped would standardise information internationally.

Although their plans were ridiculed as grandiose by their peers when Otlet and La Fontaine held their first conference in 1895, by 1900 the IIB had 300 members and their postal search service for the RBU – a kind of long-distance, painfully slow, proto-Google – was gaining more users by the month. Soon, no less a figure than Andrew Carnegie, one of the greatest industrialists of his day, was funding Otlet and La Fontaine’s projects. Their vision was being realised.

While Otlet immersed himself in the reassuring certainty of facts and strict order in his professional life, his personal life was falling apart. In 1907, his father died, leaving the family deep in debt. Two years later, Otlet divorced his wife, Fernande, who had never understood his obsessions. Less than three months into the hostilities of the first world war, his 20-year-old son, Jean, went missing at the Battle of Yser. Agonisingly, Otlet would not receive confirmation of his death until the end of the war.

Suggested Reading

Fanny Cradock’s austerity Christmas

But Otlet’s optimism remained unbowed, and he returned to earlier plans he had made with the sculptor Hendrik Andersen for the building of a “great human city, completely devoted to Peace”. Otlet soon presented this idea to the new League of Nations (itself anticipated by the Union of International Associations Otlet and La Fontaine had founded in 1910).

At its centre would be the “Mundaneum”, both a physical building and an organisation for “all men, all countries, all relations: the Earth, Life, Humanity”. By the late 1920s he was working with no less a figure than Le Corbusier to design a futuristic centre for the Mundaneum in glass and metal.

Otlet’s imagination was indeed remarkable. In his masterpiece Traité de documentation (1934), he speculated intriguingly on the technology of the future in ways that have been likened to HG Wells and Jules Verne. He wrote of cinema being expanded in ways that anticipated the Imax, and predicted the personal computer by thinking about how separate technologies could be put “together in a single unit” (later his designs for his “Mondothèque” workstation consolidated this concept).

Ultimately, he wrote, human consciousness and machine would merge so that we might “be everywhere, see everything, hear everything and know everything”.

But it was in his final major work, called simply Monde (1935), that Otlet anticipated the internet most clearly, writing of a future where “electric telescopes” connected to a central information source would mean “everyone will be able to read text, enlarged and limited to the desired subject, projected on an individual screen. In this way, everyone from his armchair will be able to contemplate creation, in whole or in certain parts.”

He even foresaw social media, writing with eerie prescience of systems where users might “participate, applaud, give ovations, sing in the chorus.”

Like many men of vision, Otlet’s thoughts could be seen as veering towards the fascistic, walking a fine line between the libertarian democratisation of knowledge and a dictatorial drive to control it. His internationalist concept of a world government, binding all humanity in a “universal society” with standardised money, laws and language, seemed alarmingly totalitarian, risking crushing minorities and difference. As Otlet’s biographer, Alex Wright, has written: “All dreams of unification are vast simplifications, and contained squarely within the utopian is the dystopian.”

Several of Otlet’s fellow travellers were sucked into the orbit of fascist regimes, being unable to resist the opportunity they offered for remaking the world. Le Corbusier had links to French fascism and accepted commissions from Mussolini. Hendrik Andersen hailed fascist Italy as the place where the “world city” would come into being.

Meanwhile, Melvil Dewey, who shared Otlet’s obsession with standardisation, from the metric system to phonetically based spelling, was a man whose prejudices were apparent in the patriarchal, western bias of his classification system, and who put a racist ban on minorities at his private members’ club.

Otlet’s own attitudes to race and power were complex. He believed in the intellectual inferiority of non-whites, and praised Leopold II even well after the atrocities in the Congo were known (“a Worker, a Builder, a Man of Accomplishment,” he wrote).

Yet Otlet also believed in universal human rights and the protection of national sovereignty, and argued for the independence of African states. In 1921, he hosted a Pan-African Congress at the Palais Mondial, where radical sentiments of black liberation were expressed. In the end, Otlet prized justice and freedom, and even if his ideas for global unification seemed imperialistic, they were driven by a conviction that it was the only guarantee of world peace.

But Otlet’s dreams of global harmony definitively ended the day he came face to face with fascism. Hugo Krüss, the Nazi administrator of occupied Europe’s libraries, had been the head of the Prussian State Library, and the two men had met as colleagues at a conference just three years before.

When Krüss arrived at the Palais Mondial in December 1940, they stood as complete opposites – the preserver of knowledge versus the man associated with book burnings. The Nazis destroyed 63 tons of Otlet’s collection and put an exhibition of Third Reich art in its place. His life’s work hollowed out, Otlet died in the winter of 1944, aged 76.

Spared by the Nazis because of possible strategic use, today the millions of cards that make up the RBU remain nestling in vast banks of miniature drawers in the basement of the Mundaneum in Mons, a museum that is partnered with Google and is dedicated to exploring Otlet’s legacy. That legacy is a complex one.

Whether he can truly be said to have foreseen the internet when his top-down system was so unlike the ephemeral, chaotic world wide web shaped by us all is debatable, and the rise of AI – information eating itself – is the very opposite of Otlet’s drive to distil information into nuggets of unchanging, empirical fact.

Otlet’s idealism was echoed in the interest many later pioneers of computer science had in the liberating potential of information and the sense of a greater mission – just as there was the “search for a set of rules which will allow computers to work together in harmony,” Tim Berners-Lee, a hippy-adjacent Unitarian Universalist, wrote in 1998, “our spiritual and social quest is for a set of rules which allow people to work together in harmony”. Yet there is something of Otlet in the “tech bros” of today, if not in their bombast, in their wild visions for the future and drive for dominion over information.

For all his complexity, Otlet is ultimately a figure to inspire. Certainly, as Elon Musk tried to rouse the “reasonable centre” of British society to take up arms at last summer’s far right march in London, we may forgive Otlet his follies given his lifelong, heartfelt investment in the principle of peace.

Otlet’s unshakable belief in the limitless potential of humanity, in spite of living through two world wars and losing a son, is an inspiring lesson in courage. But above all, his steadfast belief in the importance of facts and cross-border cooperation, as well as his vision of technology being leveraged to humanity’s benefit, rather than militating against it, are attitudes we urgently need to rediscover.