In the summer of 2019, I visited Barcelona to carry out research for a novel, The Room of Lost Steps, that I was writing about the Spanish civil war. I intended for my young hero, Theo Sterling, to experience the exultation and terror of the days of street fighting and revolution that followed the army rebellion in July 1936, and I wanted to see for myself the locations where the principal events took place.

I found that most of the buildings were still there, but that there was little or no indication of what had happened in them, and as the days went by, I began to feel like an archaeologist digging down into an extraordinary past buried just beneath the surface of the modern city.

In the novel, Theo stays with his rich parents in the Hotel Colón, whose grand facade dominated the Plaça de Catalunya, the huge bustling square at the heart of Barcelona, where wealthy citizens promenaded on marble walkways amid classical statues and fountains. The city was in a state of high excitement because the People’s Olympiad was due to begin there on July 19, and foreign athletes thronged the streets.

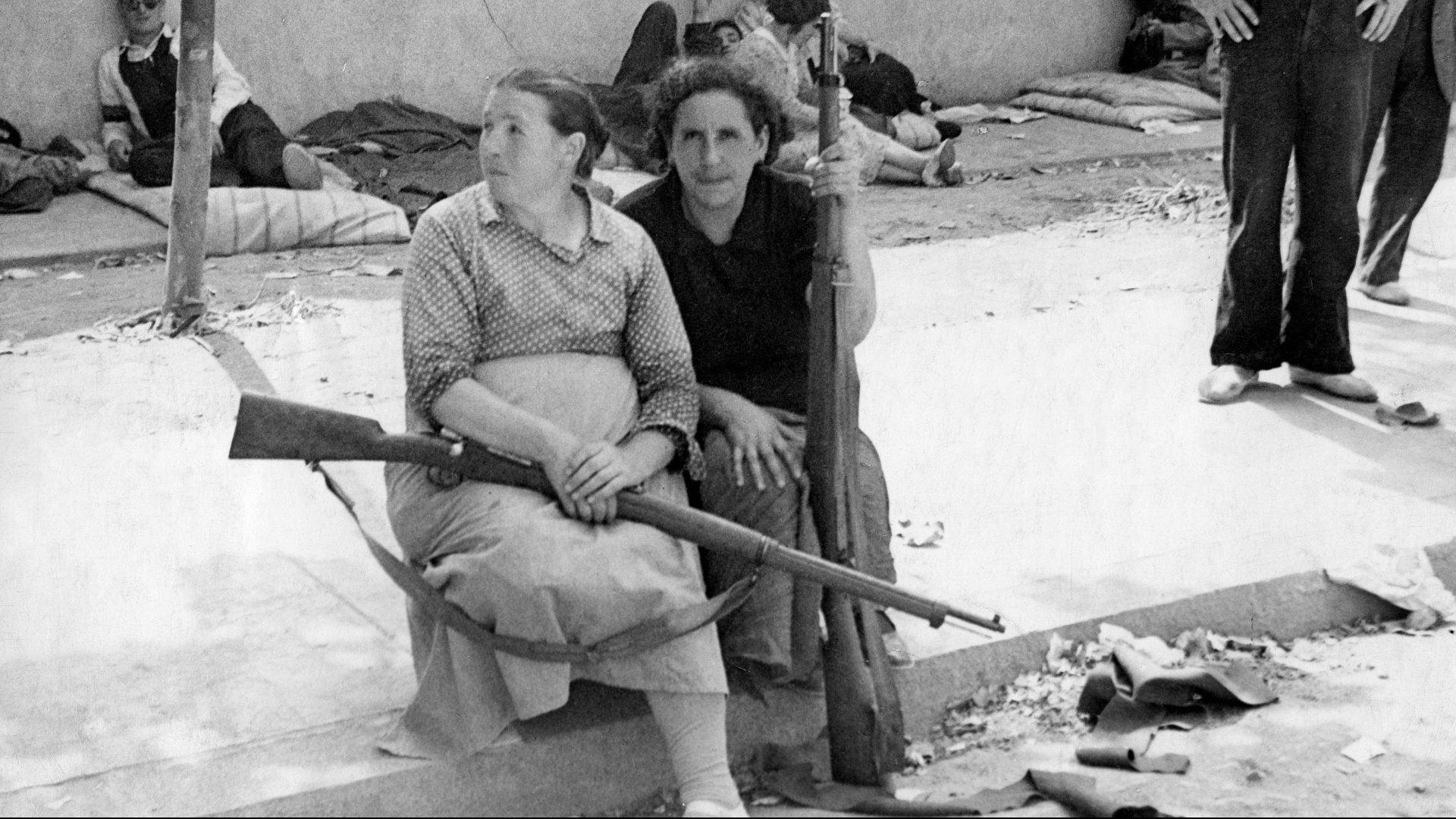

But the Games never happened, because the Spanish army attempted a dawn coup, and the boulevards and squares were transformed into a vicious battleground over which the soldiers and the Anarchist factory workers fought for control. Men and women used pickaxes and crowbars to break up the pavements, passing cobblestones down human chains to build barricades at strategic points that kept the different military units from joining forces, and slowly the soldiers were forced back.

In the Plaça de Catalunya, they took shelter in the Colón, and the novel mirrors history as Theo watches the Civil Guard commander form his men into a cordon to keep back the Anarchists and allow the soldiers to be evacuated one by one out through the hotel’s revolving entrance door, while out in the square, “ambulance men and stretcher-bearers picked their way through clouds of swarming flies as they sorted the wounded from the dead.”

Now, 90 years later, the hotel is long gone, knocked down after the civil war and replaced by a bank. The ground floor now houses an Apple Store, and there are no memorials in the square or the surrounding streets to commemorate the workers’ extraordinary victory over the might of the Spanish army. It’s as if that day has been deliberately forgotten.

The Civil Guard was not so successful the next day. Another group of soldiers had taken refuge in the Carmelite monastery on the Diagonal boulevard, and this time the Anarchists were able to break through the evacuation cordon, murdering the officers and throwing smoke bombs into the crypt to force out the friars who had been hiding there.

In the novel, Theo sees them coming out on to a side street disguised in ill-fitting civilian clothing and tries unsuccessfully to stop the Anarchists from shooting them as they tried to escape. The Carmelite church was burned like so many others in the city, and outside several, “disinterred, desiccated corpses were propped up against the pillars flanking the entrance doors with their skeletal legs dangling as if in a danse macabre, while a crowd laughed and jeered at this proof that eternal life was a lie peddled by the Church to keep the common people in thrall.”

Suggested Reading

László Krasznahorkai’s long and winding Spanish tale

Nothing could contain the Anarchists’ hatred of those whom they considered to be their oppressors. The Moulin Rouge on the Parallel Boulevard had been famous for its burlesque shows, but the revolutionaries made it the seat of the People’s Tribunal.

Three judges sat behind a long table set up on the stage, covered with two pieces of black and red cloth, handing down death sentences in scenes reminiscent of the French Revolution. The condemned were taken out to waiting lorries and driven up into the hills above Barcelona to be shot.

Nowadays, the building has been restored as a home for cabaret and jazz, and no trace remains of its other history. The churches too have been rebuilt, and the quiet, unprepossessing exterior of the Carmelite monastery gives no hint of the terrible events that once unfolded there.

In my novel, Theo returns to Barcelona a year later, after fighting for the International Brigades on the Madrid front, and finds the city utterly changed. The heady days of revolution are over. The poor are no longer able to eat for free at the Ritz Hotel and the bourgeoisie have gone back to wearing hats and ties and smart summer suits, no longer feeling the need to disguise themselves in their servants’ clothing.

The Spanish Communist Party and their Russian paymasters have infiltrated the government and made the Hotel Colón their headquarters. A huge poster of Stalin hangs down over the window of the room where Theo once stayed with the Anarchist girl Maria, whom he loves.

The communists have set up secret prisons or chekas all over the city where they murder and torture the Anarchist workers and anyone else who stands in their way. By a terrible twist of fate, Theo is forced to act as an interpreter to help persecute the very people whom he went to Spain to fight for.

In Barcelona in 2019, I saw where these chekas had once been: in Gaudí’s extraordinary architectural creation, the Güell Palace off the Ramblas, where I found the room of lost steps and set the climax of my novel, and in Montjuïc Castle, the 17th-century fortress built on a hill overlooking the city. I will never forget the moment when my guide took out an old key and led me down a winding staircase into a dark basement where “bad things had happened during the civil war.”

The dank windowless rooms were empty, but I sensed the ghosts of a cruel past waiting in the shadows. Here as elsewhere, history lies hidden, and in my novel, I have tried to bring it back to life.

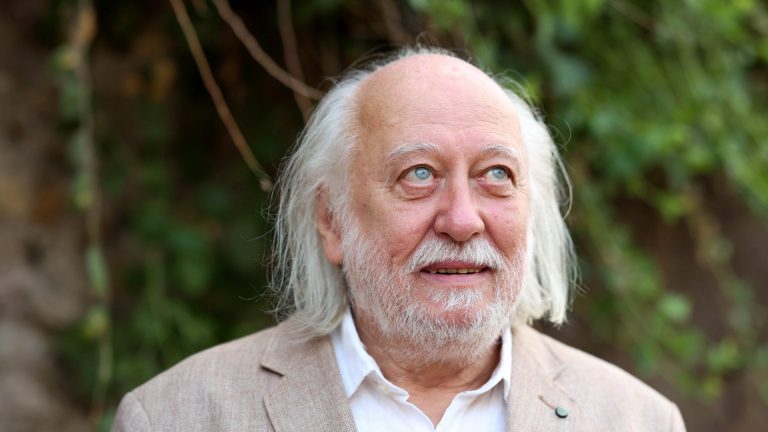

The Room of Lost Steps is published by Lake Union. Simon Tolkien is the grandson of JRR Tolkien