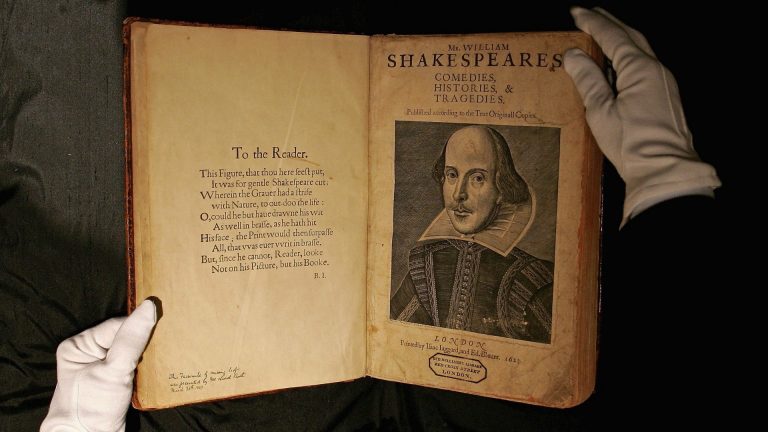

They’d always been there. Forty or so slim volumes in musty red, gold swirly writing on the spines. They belonged to my father’s father, who died before I was born, then my father had them. All of Shakespeare’s plays, a series published by Cassell and Co in 1908. Most of them a bit battered. Most of them read, some of them much-read.

After my father died, I took them home. It seemed wrong to consign them to the skip, and they weren’t worth much to anyone except me, for they represented three generations of Shakespeare fans. I had read Hamlet to my father when he was on his deathbed: “’tis bitter cold and I am sick at heart”.

The books stood to attention on a shelf in the spare room for a couple of years, and I was pleased to see them there. Then one day I thought: well, better read them then. Read them in chronological order. So I started with The Taming of the Shrew and several months later and a couple of weeks ago I was reading the final lines of Two Noble Kinsmen, which Shakespeare wrote in partnership with John Fletcher. That’s 39 plays.

The Cassell edition is excellent. The books fit nicely in the hand, the text is clear and readable: no poncing and above all, no notes. A bit of a glossary at the back, that’s all. You have no option but to read the damn play.

I wasn’t studying Shakespeare. I wasn’t reading Shakespeare to pass an exam. I wasn’t reading Shakespeare to drop quotations into conversation. (Fancy some midnight mushrumps?) I wasn’t reading Shakespeare to write an academic essay: the theme of loss in Hamlet, or Shakespeare and the idea of kingship. Last time I wrote an essay about Shakespeare – 1971 – I received a gamma, with the implication that gamma minus would have more appropriate.

No. I just read the damn plays and I enjoyed the damn plays. Great stories, great characters, great language. Finish one and there’s another just as good or even better.

But what about the horrors? The really dull plays that nobody ever reads? What about Titus Andronicus and The Comedy of Errors? Well OK, they’re not as good as Macbeth or A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but that’s true of every other play ever written, apart from a few others on the same shelf.

The fact is that Shakespeare’s bad plays are better than most people’s good plays, and even his callow youthful efforts have hints of greatness. The tangled romping of the two sets of twins in the Comedy is sharp and clever and agreeably silly: sort of primordial PG Wodehouse.

Titus is so grotesque it’s silly in a different way: in the climactic scene, Titus’s enemies are baked in a pie and consumed at a great feast. But even here Shakespearean greatness breaks out almost uncontrollably with Aaron the Moor’s unrepentant ardour for evil.

What’s more, every single play is an essential chapter in one great story: the arc of Shakespeare’s genius. In one 14-month period he wrote King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus. Any single one of these plays would be enough to secure any other playwright’s reputation for all time.

I soon learned that reading Shakespeare is not actually difficult. Perhaps we think it is because most of us read him at school. But adjustment to the language of Elizabethan and Jacobean England is simple enough: almost imperceptibly you’re accepting that humorous means moody – affected by the humours – rather than jokey, that trow means know and want means lack.

Some of the comedy scenes require a little pause for thought or a little judicious hurrying past, but there’s much that’s clear enough, and even funny. In Measure for Measure, Pompey the pimp is asked about Mistress Overdone. “Hath she had any more than one husband?” “Nine sir. Overdone by the last.”

And then you turn a page and you’re off on the great soaring heady tides of language: deep, disturbing and at times overpowering: swept away by a tsunami of words: “this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o’er-hanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire – why it appeareth no other thing to me than a vile and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man…”

There’s another joy of reading Shakespeare: no bloody actors to get in the way. I’ve nothing against actors – after all, I married one – but I went to a recent highly praised production of the Dream at the Royal Shakespeare Company and found that most of the actors were unable or unwilling to speak verse.

Perhaps they had lost faith in the audience’s capacity to enjoy Shakespeare, or perhaps they wanted to put their own personal stamp on every line, but mostly they SHOUTED AT THE TOP OF THEIR VOICES or gabbledsofastyoucouldn’tpossiblyunderstandthem.

Better still, the reader has no directors to worry about. Clive James wrote about watching Peter Hall’s Troilus and Cressida, “previously known as Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida”. Directors like to present Caliban as a heroic freedom fighter against the vile forces of colonialism, never mind his attempted rape and his plot to commit murder.

There was an otherwise excellent television film of the Dream directed by Russell T Davies, taking a break from Doctor Who. It had Maxine Peake as a terrific Titania and Matt Lucas as a wonderfully sweet-natured Bottom. But it also had Theseus as a mad dictator and his wife-to-be, Hippolyta, (literally) wheeled on to the set bound, gagged and wearing a straitjacket. I’m researching a book for directors: 100 Ways of Improving Shakespeare. It will comprise 100 blank pages.

But readers face no such irritations. We are the director as well as the leading actor and best supporting player. We have no reason to lose faith with Shakespeare. We aren’t restricted to a single interpretation of any theme or character: we can savour them all at the same time and be as myriad-minded as Shakespeare himself.

It’s supposed to be heresy to say that Shakespeare is better for readers than for audiences, but at least there’s only one’s own egomania and vanity getting between Shakespeare and his dear readers.

We’re all so busy these days that impossible wonders often seem humdrum: hurrying over London Bridge looking at St Paul’s, a busker playing Bach, a Starry Night fridge magnet. We tend to accept Shakespeare’s genius in the same way: sure, of course he’s great, but I’m in a hurry.

But the plays are an unending astonishment when you sit down and read them. So many plays and so many of them quite unspeakably brilliant – and they all came from the hurrying quill of a single inky-fingered hand. No sooner had he finished the joyous As You Like It than he was writing the murder of Julius Caesar, the troubles of Brutus and the triumph of the arch-politician Mark Antony.

Shakespeare could turn – and turn on a sixpence – from tragedy to comedy, and be a master of both. As soon as Duncan is murdered, the drunken porter is off on a mad fantasy about keeping the gates of hell. He then discusses the effects of drink: “It provokes the desire, but it takes away the performance.”

As you read, you soon set aside the childish need to seek goodies and baddies. We want Prospero to be wholly admirable, but soon discover that he is wrong as well as wronged. We want Iago to be repulsive, and yet he is so brilliantly evil that there’s something sneakily attractive about him. Perhaps there’s an Iago and an Othello in us all.

The so-called problem plays are problematic only if we’re looking for a single moral thread to guide us through the maze. Things become clearer on a leisurely reading: in Measure for Measure everyone is clearly mad, and in Troilus and Cressida all the noble characters are complete shits.

Such verdicts are the luxury of the reader with no deadline to meet, no audience to please and no tutor to impress. When you try to get clever with Shakespeare you can end up like poor TS Eliot, who somehow managed to convince himself that Hamlet was “an artistic failure”. We mere readers can unashamedly read because we love the story, because we have a passion for the sexier characters, because we want to be one of the cooler characters, because we are utterly seduced by the grace of language and don’t give a stuff about analysis.

What was the best bit about reading Shakespeare? The wisdom of Juliet, the wit of Rosalind, the amorous folly of Titania, the glory of Cleopatra – there must have been some wonderfully talented boys in The King’s Men, that Shakespeare could entrust such roles to them. But the choice goes on: the intellectual rigour of Hamlet, the loving marriage of the Macbeths, the apparent impotence of Othello.

Life is perfect and wholly joyous at the end of the great comedies, and we have no doubt at all that “Jack shall have Jill, nought shall go ill, the man shall have his mare again and all shall be well”. And yet when we step out on to the heath with King Lear we accept that the only truth is that life is bad and then you die, and the only sanity lies in the brutal one-liners of the Fool: “Marry, here’s grace and a cod-piece; that’s a wise man and a fool”.

Suggested Reading

Shakespeare conquered the world elsewhere

It was Ben Jonson, a playwright who wrote some fine satires but couldn’t write a tragedy to save his life, who said that he loved Shakespeare “this side idolatry”. The term Bardolatry has been coined for those with a too fervent and uncritical admiration for Shakespeare.

But bardolatry is the only sane and balanced response to a reading of those 39 plays. Who can compare with Shakespeare? If we restrict the competition to mere playwrights, it’s Real Madrid against Barnet, Woking and Hartlepool in the National League. No one has written an individual play half as good as Hamlet or As You Like It. No one else has a dramatic oeuvre that even gets close. No one has produced characters that ring and echo down the ages: and I haven’t even mentioned Falstaff, Richard III, Portia, Viola and Edmund.

Who are you offering in competition with all that lot? The stilted tragedies of Racine and Corneille, the so-so comedies of Molière, the rambling of Goethe’s Faust and the ranting of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, the claustrophobic horrors of Ibsen, the self-admiring cleverness of Shaw?

If you seek comparison with Shakespeare, you must step outside drama – perhaps even wondering if drama isn’t a second-class art in any other hands – and look at the great writers in other forms: Joyce, Proust, Dante, Milton, Melville. Or at other arts entirely: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, van Gogh, Botticelli, Leonardo.

It’s not idolatry to accept that the works of these artists inspire not admiration but awe. When you read Shakespeare from beginning to end, you begin to grasp the extent of his greatness – not as received wisdom, but as lived experience.

I’m tempted to take one tiny thing to stand for all the immensity of that 39-volume voyage. Perhaps the moment when Hamlet describes his own play, The Mousetrap: “Marry, this is miching mallecho”. Or perhaps when Rosalind, a woman who is played by a boy and is now disguised as a man who is pretending to be her own lover’s lover, and she (he?) tells him: “Come woo me, woo me, for now I am in holiday humour and like enough to consent.”

But the fact is that the best thing about reading Shakespeare is the ineffable everythingness of it all: the glory and wonder of words and characters and stories and love and hate and love and words, words, words.

How can I follow this, one of the great reading experiences of a lifetime? That’s easy. I have just finished The Taming of the Shrew again.

One down, 38 to go.

Simon Barnes is an author and journalist