The Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute in Bologna was originally built in the 1600s as a monastery, where monks studied medicine, botanics and alchemy. But it is no ordinary hospital – it’s also a stunning museum. Very few people, even Italians, seem to know this.

I never thought a place like this could exist. You don’t need to be a patient to go inside – the Rizzoli is open to the public. There are no gates, and the security guards at the entrance smile as you walk in.

As I walked along the internal frescoed cloister overlooking a flower garden with decorated wells where the monks used to draw water, you come across artistic wonders normally associated with a high Roman church, or an aristocratic palazzo.

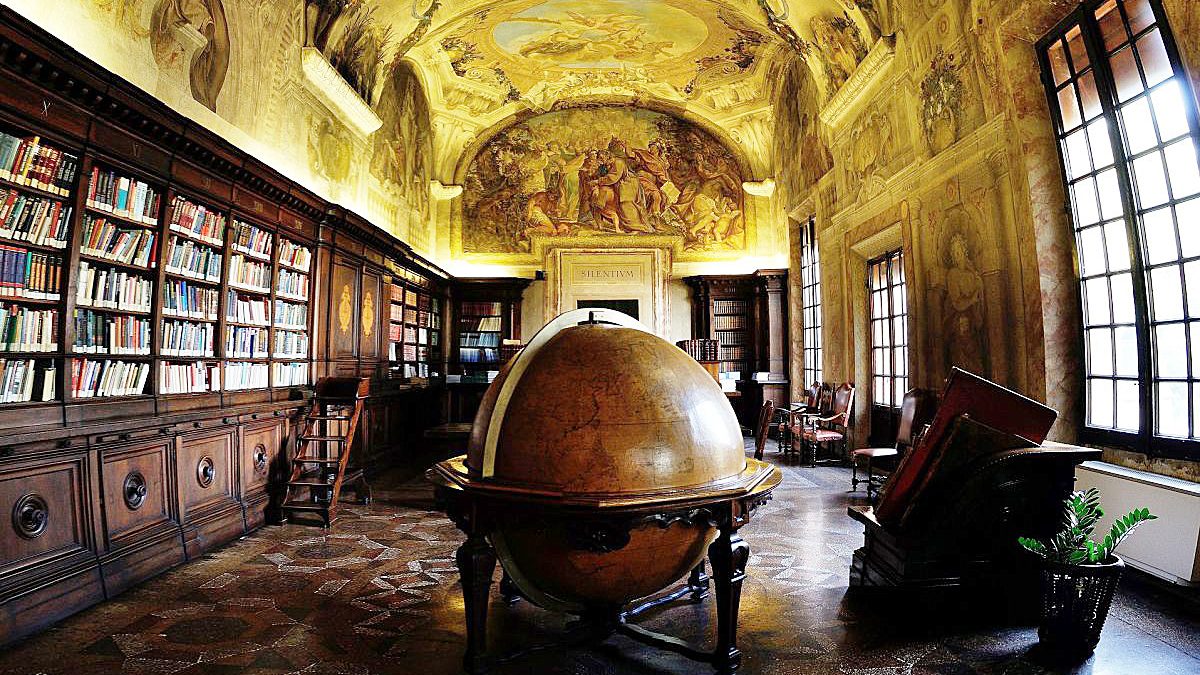

Professor Cesare Faldini, the director of the institute, gave me the grand tour. We passed by a few recovering patients on crutches, and he showed me bright Renaissance frescoes, stone statues of great past surgeons, a frescoed library stacked with medieval manuscripts on medicine and a map from the 1700s – without Australia on it. The brightness of the painted vaulted ceilings, some depicting mythological and apocalyptic scenes, was dazzling.

“I feel lucky to work here. The surrounding beauty is intoxicating. When I first arrived 29 years ago, I couldn’t stop staring at the frescoes, the cloister and the long corridors. It was like seeing the Sistine Chapel for the first time every single day. I could feel the history. The Rizzoli is not the usual dull, claustrophobic, cold hospital,” Faldini told me.

The professor is a piece of art himself, a hardcore Tuscan who can’t stand still for more than two minutes. He’s famous for dealing with extremely “delicate cases” rejected by other hospitals.

With over 200 patients across Italy, he operates 10 hours per day (spine surgery is his forte), tours the world to promote the Rizzoli’s achievements, leads humanitarian missions in Africa and in his spare time plays the trumpet.

He spoke and moved so fast I could barely follow him.

“In time, I came to understand that all this wonderful art and architecture convey the message that past scientific and medical heritage is the key to the future, to cutting-edge innovation and research in orthopaedics. The artistic beauty pushes me to do more in the field,” said Faldini.

We went into a narrow room with a squeaky wooden beam floor where early surgical instruments were on display along with accounts of how bodily deformities were treated centuries ago. There are photos of kids with hunch backs and women with crooked legs, while behind glass counters all sorts of terrible surgical tools are showcased. Those sent shivers up my spine.

Suggested Reading

The downside of living the Italian dream

But for me the icing on the cake was the second, hidden internal cloister I discovered behind this showroom. Exceptionally shaped like an octagon, it is painted in a reddish-brown, Pompeii-style pastel colour. I could see traces of worn out frescoes, blurry left-over images of once vibrant paintings.

A bunch of students – yes, the Rizzoli also hosts the faculty of orthopaedics of Bologna’s university – were chatting under the cloister’s vaults. I think most were oblivious to the beauty around them and had no idea how lucky they are to be studying inside a museum – perhaps after a while you take anything for granted.

At the end of the tour Faldini treated me to a cornetto with Nutella at the hospital’s bar, and I came across yet another marvellous religious wall painting located in front of a monumental marble staircase – so wide that a pair of horses could climb it. I asked around but apparently the artist responsible is “unknown” or considered minor, which seemed extraordinary.

When I walked outside into the hospital’s back yard, I was surprised to see it had been turned into a park with benches. There were people chatting under the shade of a huge Lebanese cedar and others walking their dogs while joggers passed by. A path led all the way to the centre of Bologna.

Overwhelmed by what I had seen, I sat. If only more Italian hospitals were made as welcoming as the Rizzoli, I think patients would be less scared to go inside in search of help.

Silvia Marchetti is a freelance reporter living in Rome