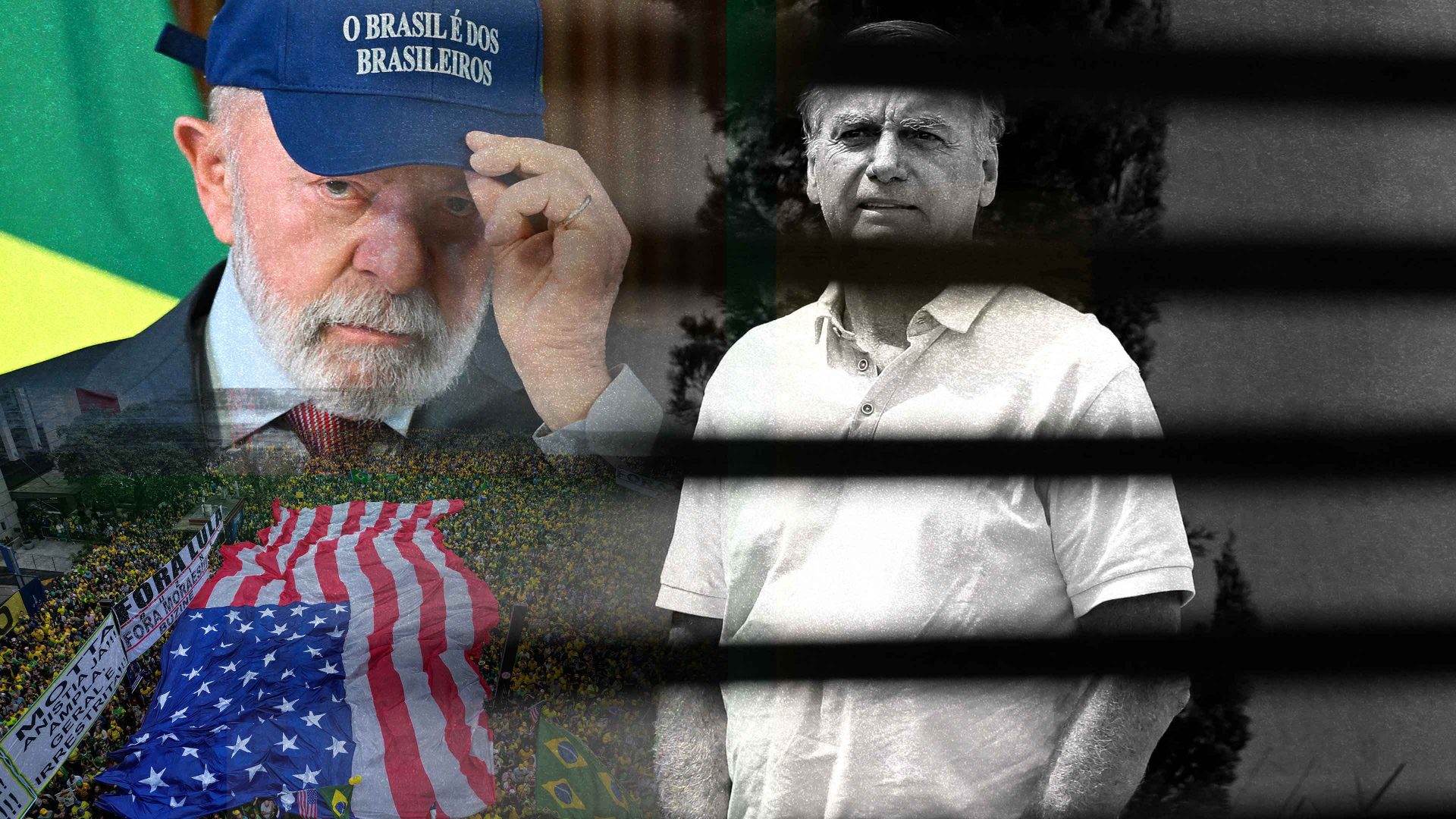

Jair Bolsonaro used to boast that “only God” could remove him from the presidency of Brazil. Now, confined to house arrest and reportedly “panicking” at the prospect of jail time, his authoritarian populist swagger has faded.

In September, the hard right former president received a 27-year prison sentence for leading a failed coup attempt following his 2022 election loss to his bitter rival, the leftist Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva. Several senior military officials also received lengthy prison sentences for their role in the plot.

Citing ill health, Bolsonaro didn’t attend the hearings at Brasília’s Supreme Court Palace, a modernist landmark designed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer. On January 8, 2023, the building had been ransacked, along with the presidential palace and congress, by a mob of more than 1,000 frenzied Bolsonaro supporters, who vandalised priceless artefacts. Some of them even defecated inside.

The attack, considered the final push of the failed coup, drew comparisons with January 6, 2021 in Washington DC, when Donald Trump’s supporters stormed the Capitol after his 2020 defeat to Joe Biden. But as investigations have shown, Bolsonaro’s attempted coup was a far more serious threat to Brazil’s young democracy: some plotters were considering the assassinations of Lula, his vice-president and a Supreme Court justice.

According to Carlos Fico, a history professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the author of Brazilian Authoritarian Utopia, since 1889, Brazil has suffered 15 coups or attempted coups, none of which resulted in punishment for the plotters. “All failed coup attempts were pardoned and this impunity served as an incentive for new coups,” he said. “Coup plotters pardoned in one case later committed the same practice.”

Suggested Reading

The Brazilian motorway that thinks it’s a park

In the aftermath of the conviction, Bolsonaro’s allies in congress scrambled for an amnesty. They formed an alliance of convenience with Brasília’s power brokers, the so-called “big centre”, a vast bloc of right wing politicians skilled in the dark arts of shady backroom deals.

Late night in the lower house, lawmakers pushed through the so-called “immunity bill” aimed at curbing investigations into their own ranks. However, this backfired and after mass street protests, the measures were buried.

Meanwhile, Trump, of whom Bolsonaro has always been an outspoken fanboy, called the conviction terrible. Secretary of state and Latin America hawk Marco Rubio, said the United States would “respond accordingly to this witch hunt”. Brazil had already received 50% tariffs on a wide range of products in August, the result of lobbying by Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo in Washington.

But then, a surprise. At the UN general assembly, in the same corridors where in 2019 Bolsonaro told Trump he loved him, the US president crossed paths with president Lula.

“He seemed like a very nice man, actually. He liked me, I liked him… we had excellent chemistry. It’s a good sign,” Trump said of Lula, arguably Latin America’s most successful statesmen of the 21st century, who had just delivered a fiery speech defending Brazil’s sovereignty.

Bolsonarismo, the term coined to describe the former president’s insurgent, hard-right, violently anti-democratic movement that changed the face of Brazilian politics, appears on the back foot, at least for now. Next year’s elections, in which two-thirds of seats are up for grabs in the senate, will be a test of his movement’s legacy.

With or without Bolsonaro, Brazil’s path remains fraught with challenges. Embedded oligarchies, reactionary elites and cold war era ghosts remain active, and are prepared to mobilise when their interests are threatened. External factors, from commodity price fluctuations to outright meddling from foreign governments, as seen most recently with Trump’s tariffs, add to that sense of volatility.

Readers may be familiar with the overused cliché that “Brazil is the country of the future… and always will be”. That old line captures the frustration so many people feel with the age-old problems that Brazil has sought to overcome, often making important inroads, before suffering setbacks. On the face of it, the country should be a South American superpower. It is the world’s ninth-largest economy and has the seventh-largest population. It is endowed with spectacular natural resources across its vast, diverse territory.

It has world-class research institutions and leads global production in coffee, orange juice, iron ore and other commodities. Nearly 90% of its electricity comes from renewables and its central bank-backed instant payment system Pix has been so successful that Trump targeted it in recent sanctions for supposedly undermining North America’s own payments systems.

Yet Brazil is among the most violent and unequal societies of the G20 group of nations, a legacy that stems directly from its brutal colonial past. While the United States was fundamentally a settler colony, with all the atrocities that entailed, Brazil began as an extractive colony.

“Brazil began as a slave society, as a society geared up for exports,” said Thiago Krause, a historian of Brazil and the Atlantic world and associate professor at Wayne State University in Detroit. “That’s the first and most important colonial legacy, all of the others are derived from that.”

Portuguese explorers arrived in 1500 and exploited Indigenous labourers to harvest and export brazilwood timber. After brazilwood, from which the colony would earn its name, the Portuguese planted sugarcane, as they had previously done in their Atlantic island colonies of Madeira, Cape Verde and São Tomé.

Brazil’s lush tropical climate, fertile soil and endless land provided the ideal conditions, and by the mid-1500s, the Portuguese began importing large numbers of enslaved Africans. Brazil’s sugar boom entrenched inequality, most evidently in the deeply uneven ownership of land. Life on the plantations was brutal, with high mortality rates.

It was also harsh in the mines. During Brazil’s 18th-century gold boom, Portugal extracted over 800 tons of the metal, which it used to pay for British imports, including textiles. That money flooded into British banks, which helped fund the Industrial Revolution and turn London into a financial powerhouse.

When, in 1822, Brazil finally declared independence from the Portuguese crown, the new state preserved the former colonial structures and retained the practice of slavery, which expanded greatly. Overall, Brazil imported some 4m enslaved Africans, more than ten times the number brought to the US.

Large numbers of those slaves escaped and went on to found fierce resistance societies, and if part of Brazil’s history is defined by the brutality imposed from the central authorities, then another, equally important part is determined by popular resistance. In 1888, Brazil abolished slavery, the last country in the western hemisphere to do so. A year later, Brazil’s first republic was formed via a military coup that deposed the monarchy.

That period of authoritarian rule lasted, on and off, until the military dictatorship of 1964-1985, which began when generals forcefully deposed left-leaning Joao Goulart, with backing from the US. Inequality had declined modestly in the post-war period, but it went up sharply in the early years of the dictatorship. Hundreds of political activists were killed or disappeared, and thousands were tortured. In the country’s vast interior, peasants and indigenous people were killed or driven from their land. Brazil’s military regime contributed to the development of repressive tactics that were later integrated into Operation Condor, a Cold War-era campaign of transnational state terror supported by the United States.

“The US backed military coup of 1964 was seen as a success and a model both by foreign policy officials in the United States and right-wing forces in other countries in South America,” said Vincent Bevins, author of The Jakarta Method, a study of US anti-communist foreign policy.

However, unlike Argentina and Chile, Brazil never held trials of those responsible for atrocities during the periods of dictatorship. In 1979, Brazil passed an amnesty to political prisoners, exiles, and dissidents who were persecuted during the military regime. But crucially, it also shielded military officials and state agents from prosecution for crimes including torture, forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

Bolsonaro himself has always been an outspoken advocate for the most violent and depraved elements of Brazil’s dictatorship, often paying homage to the notorious torturer Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, whom he called “a national hero”. But having defined his political career with violent anti-democratic rhetoric, Bolsonaro’s authoritarian tendencies have now caught up with him.

Currently, it seems the best he can hope for is a reduction in his sentence. However, at 70 years old and in declining health, it’s unlikely he would serve much meaningful jail time.

Such is the unforgiving nature of Brazil’s murky right-wing machine politics that, in Brasília, it’s widely reported that the establishment right-wing wants Bolsonaro’s case wrapped up quickly so it can move on and back a different right-wing presidential candidate in 2026.

Having left the presidency in 2010 with record approval ratings, jailed in 2018 on corruption charges that were later overturned, then making a stunning comeback by winning close-fought elections against Bolsonaro in 2022, Lula leads in the polls. Yet at 80 years old, the former trade unionist understandably says another run depends on his health. But his unique standing in Brazil’s political history, which derives from his defiance of the former military government, makes it all the more difficult to find a suitable successor. Next year’s race will likely be as close as in 2022.

What is certain is that Bolsonaro’s conviction marks a historic shift: Brazil has finally held coup plotters accountable. There is a cautious sense of optimism that Latin America’s largest economy might turn the page on recent political upheaval and break from its authoritarian past.

But democracy is a never-ending battle. It seems Brazil’s fate is to be permanently on the frontline.

Sam Cowie is a British journalist based in São Paulo, Brazil. He is a regular contributor to the Guardian, Al Jazeera and the BBC, where he has a bi-weekly radio slot