The Lebanese civil war was less than a year old when, on January 18, 1976, hell came to La Quarantaine. Deadly exchanges between the militias of the PLO-supporting left and the Christian, right wing Phalange had begun the previous spring. Each week seemed to bring new tragedy to the streets of Beirut: a drive-by shooting at a baptism, an ambush on a bus taking activists home from a rally, a long-running battle that raged through the city’s hotel district.

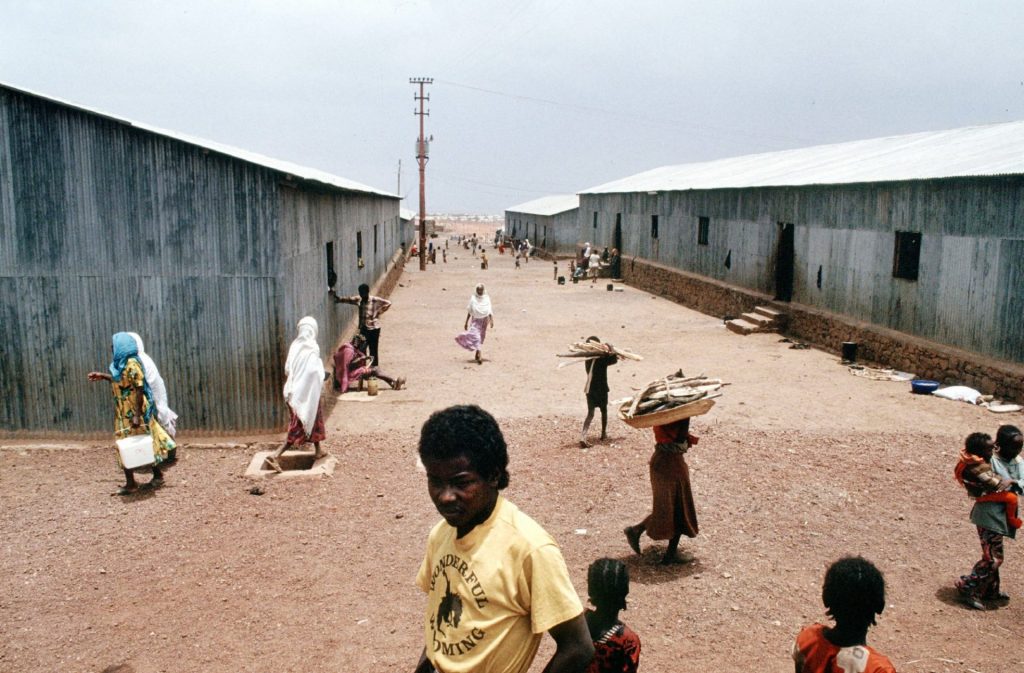

Now, the Phalangists raided a favela of Palestinian refugees in the eastern area known to locals as Karantina, also known as a base for PLO paramilitaries. The locals were supposed to have been cleared out earlier, but many – evidently – had stuck around. Anywhere between 600 and 1,500 died, and the Washington Post reported: “Many Lebanese Muslim men and boys were rounded up and separated from the women and children and massacred, while the women and young girls were violently raped and robbed.”

The defining image of the La Quarantaine massacre was taken by Françoise “Fifi” Demulder, a tall and glamorous Parisian who might have found a home on the catwalk but instead was, said a friend after her death, “never far from the front line”. Her photograph seems to have the composition of a Renaissance masterpiece: The woman pleading with a masked Phalangist, who is holding a second world war rifle, the burning building behind her – possibly the woman’s home, the parents and children scurrying for safety.

It is a portrait of despair and of what Demulder called the all-consuming “demented hatred” of war. It consumed the militia man with the rifle, who she later learned had killed himself in a game of Russian roulette. By then, the image had made her the first woman to win the World Press Photo of the Year award.

Suggested Reading

Robert Longo’s black mirrors

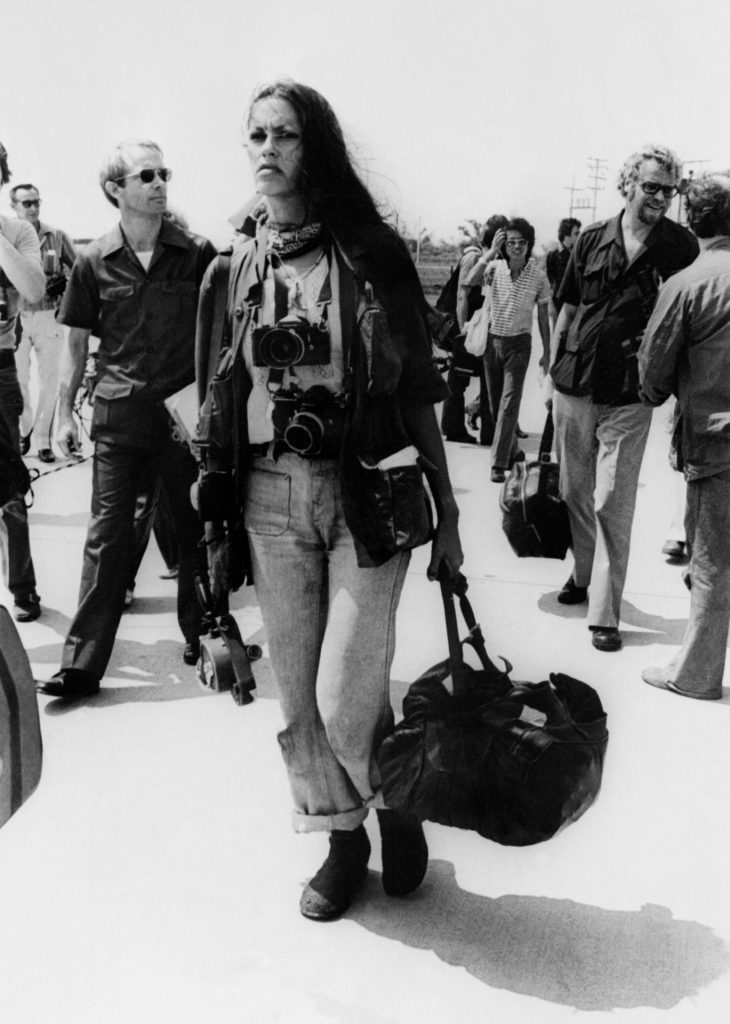

Fifi Demulder was a philosophy student and a model when, in the early 1970s, she followed her photographer boyfriend Yves Billy on an assignment to Vietnam. “From that point on her life was no longer her own. After that, all she did was ‘see’,” wrote her friend, the renowned French journalist Jacques-Marie Bourget.

Her new life took her to war zones across the world, through which she strolled, Bourget wrote, “like Moses through the Red Sea… her eye would light on what she knew was essential, in that split second; there would be one click and then a smile. She was from a different realm, had the elegance of a ballerina, and passed virtually unnoticed, nothing more than a little bird landing on a branch.”

Sadie Harper is a journalist from Connecticut, USA