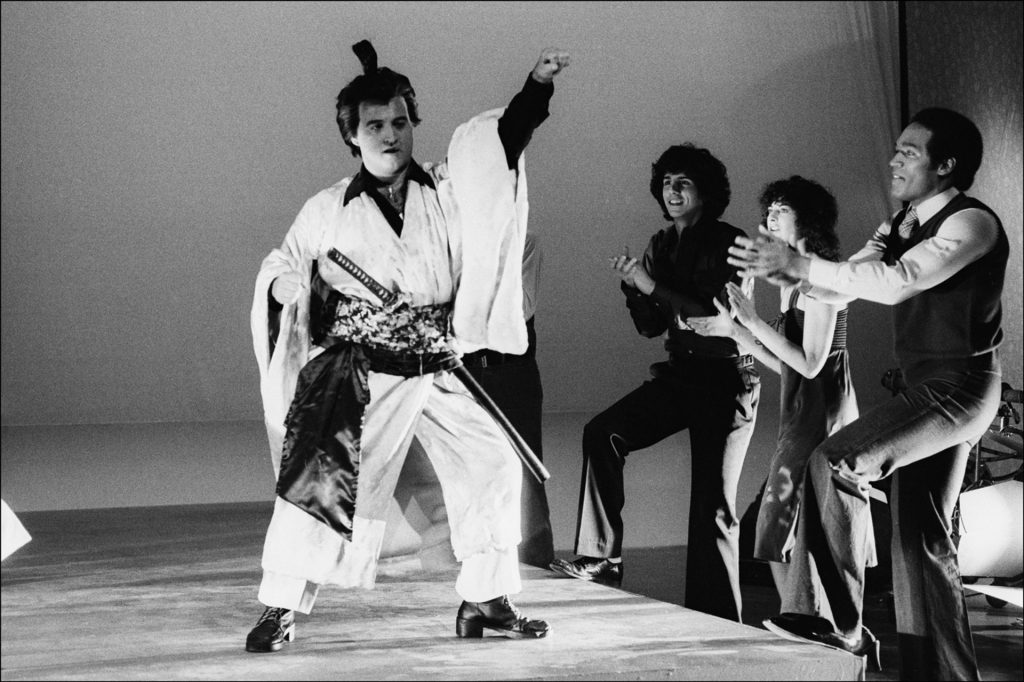

On the evening of January 17, 1976, now half a century ago, the writer and actor Buck Henry walked into a delicatessen and ordered a sandwich. The man behind the counter delivered it, and when Henry asked for it to be cut in half, the worker did so by bringing his katana – the curved, single-edged Japanese sword – down upon it with huge comic violence. The studio audience at Saturday Night Live, a fledgling show that had then been been running for only three months, went wild.

John Belushi had appeared as a samurai on SNL once before, opposite guest host Richard Pryor a month earlier. When Henry’s turn to host came, he had three suggestions for showrunner Lorne Michaels: start repeating characters from hit sketches to build a following, bring back Belushi as the samurai, and put him in ordinary situations. “Every comedy I’ve ever been involved with… depends on repetition of a kind,” Henry told writer Mike Sacks years later. “Why not do the samurai character in different situations over and over again? The repetition is funny in and of itself.”

“Samurai Delicatessen” was followed by another 14 sketches, including “Samurai Stockbroker” and “Samurai Hotel Concierge”. The character, now dubbed Samurai Futaba, helped make Saturday Night Live and its recurring grotesques a must-watch, and Belushi a Hollywood star. But it also granted icon status in the west to the samurai, the Japanese elite warrior class that rose in the 12th century before disappearing in the late 19th.

Today, samurai characters have leaked from manga, anime and the films of Akira Kurosawa, Takashi Miike and more into a shared global culture. The original warriors and their traditions are now the subject of a major exhibition, with a lavishly illustrated accompanying book, at the British Museum.

To modern audiences, Belushi’s samurai, with his pidgin phrases and cartoonish savagery, can be a difficult watch. Despite that, Futaba’s impact on perceptions of Japan in the US and the wider west was beneficial. Forty years before Belushi, images of samurai had featured in Imperial Japanese propaganda, as well as being co-opted by German and Italian fascists. Now, as Alisa Freedman writes in Samurai, a country that had been the enemy just a generation earlier was being redefined by “colourful, jokey versions of its historical figures and international exports, therefore shrouding any racism, economic tensions or historical memories of violence and war.” Japan was no longer evil, but cool.

Two months after “Samurai Delicatessen” aired, filming began on an American movie that nodded towards samurai aesthetics, borrowed freely from Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress and had at its heart a warrior elite who adhered to a code of discipline and morality while carrying specially crafted katanas made of light. Released in May 1977, Star Wars was a worldwide sensation, and 100 years after they disappeared, the samurai were back in earnest.

Images: The Trustees of the British Museum; National Museum of Japanese History; Museum of Oriental Art, Venice

Samurai is at the British Museum from February 3 to May 4. The accompanying book, by Rosina Buckland and Oleg Benesch, is published by the British Museum Press, £45