Clatt Primary, St Dominic’s Catholic, Highbury Quadrant, St Peter in Chains, St Bartholomew’s CofE. A few years ago, these schools were full of noisy young children and their teachers. Now they stand empty, their playgrounds silent, weeds beginning to creep up the drinking fountains and climbing frames. The Education Policy Institute has estimated that several hundred more will have closed by the end of the decade.

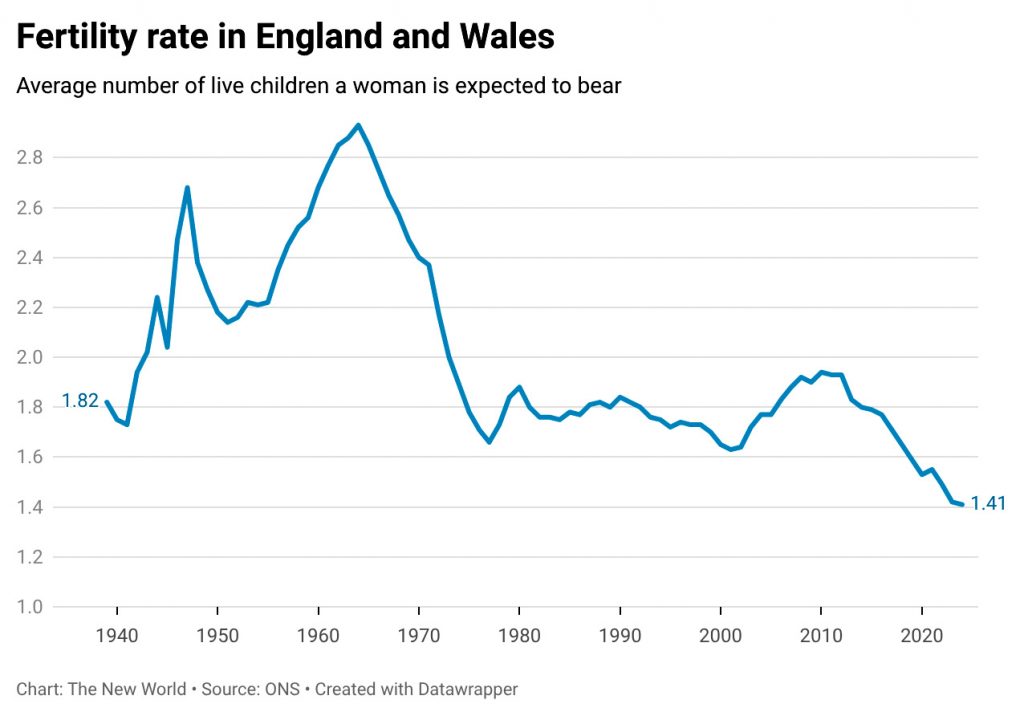

The birth rate in England and Wales was 1.41 last year, the lowest figure on record. In Scotland it was just 1.25 and in Edinburgh it fell below one. Only children, who used to be a slightly pitied minority, now account for about 44% of families with a parent. Without a lot of immigration, and unless the rate rises to just above two, the population of the UK will shrink.

Aunts and uncles will become rarer. In time, there will be fewer people to take on the burden of caring for elderly parents and supporting retirees. Immigration could bolster the overall population – although it has fallen sharply since the early 2020s – but it will make very little difference to the number of children, and is a short-term fix. We will be an older, more tired nation.

Do we care? Some people, especially on the left, do not. “One and done” is a thing on Mumsnet. Some prefer to look after one child generously rather than crowd two or three into a small house with a big mortgage, and struggle to pay for holidays.

Those who support the philosophy of degrowth – that by consuming less, we can preserve more of the world’s resources – think fewer bodies means lower carbon emissions. Recently, in the Guardian, a woman explained that she had aborted her third pregnancy due to climate anxiety, although she now regretted it.

Others argue that it is not the state’s business to encourage people to have more children, especially when it is down to women to shoulder most of that responsibility. Their view is that the left did not champion the right of women to work and control their own fertility, only to start nudging them back to the maternity ward and the playgroup.

It hardly helps that in the past decade, it has been Hungary – led by a far right government with a visceral loathing of immigration – that has implemented the most generous pro-natal policies in Europe. You tend to hear that they haven’t worked, although this is not quite true: the birth rate rose from 1.2 in 2011 to 1.6 and is now hovering around 1.4.

Some right wing pro-natalists certainly do indulge in nativism. Nigel Farage, who briefly supported restoring benefits to families with three or more children, has since changed his mind on the grounds that immigrants would benefit too. But in the last couple of years a few people on the left have begun to talk about the birth rate. One of them is Aveek Bhattacharya, who co-edited a report for the Social Market Foundation last year on “the progressive case for making it easier to have children”.

The education secretary Bridget Phillipson and Starmerite Labour minister Josh Simons have both described the low birth rate as a problem. “The fertility rate is the indicator of the health of a society,” says Bhattacharya. “If people don’t feel optimistic about the future, that is an indicator of something amiss in society.”

But whatever is amiss does not only apply to the UK, nor even just Europe. Jamaica, South Korea, Chile and Thailand have lower birth rates than Britain. It would be logical to draw the conclusion that women who can do paid work and enjoy financial independence simply do not want to have many babies.

Paul Morland, a demographer and the author of No One Left: Why the World Needs More Children, questions that assumption. Surveys suggest, he says, that women tend to want two to three children. They end up having fewer because the state does not support them. “We need to completely re-orient the welfare state around families and children, with tax cuts for people with children,” he says. Shrinking societies do not prosper: “We are much better off now there are eight billion of us. We eat more and better. Infant mortality is lower. And the reason for that is we are more inventive. Within reason, a large human population is very good at resolving its issues. When it was a small population, it was much worse.”

Sex education in schools, he believes, should focus on pregnancy as a potential aspiration for the future rather than something to be avoided for as long as possible. Companies should provide nurseries rather than gyms. “It’s not a woman problem, it’s a human problem. Men obviously have to play their part, and grandparents, as my wife and I now do. Part of the cultural shift that’s needed is for young men to feel that being there for a young family is the best thing they could do.”

Suggested Reading

The wellness scam economy of the algorithm age

A cultural shift like that is something that many people on the left instinctively distrust. To them, it smacks of tradwives, MAGA-style evangelism and, potentially, an erosion of the right to abortion. It feeds into reactionary narratives about selfish women who prize their own success above child-rearing. In countries with a strained or inadequate welfare state, it implicitly puts the onus on women to sacrifice their autonomy, rather than on the state to make it easier to look after children.

But Bhattacharya believes the left needs to wake up to the consequences of plunging birth rates. “For most of human history, falling fertility rates have been something to welcome because they’ve led to greater opportunities for women. We’re at a pivotal point where the implications are more challenging.

“The way to square that circle a bit is to say that [having children] is socially important work, and at a societal level we should care about this without restricting people’s choice.”

But it is not entirely clear what policies would actually encourage people to have more children. Things that used to work – medals for fecund mothers in late 19th-century France, for example – are not going to inspire a woman who is paying half the mortgage. People do not always respond to the signals politicians send them. The two-child benefit limit was supposed to deter poor families from having children. In fact, many of those affected were unaware of it or had their third child when times were good, only later finding themselves in hardship.

Many countries already have pro-natal policies, but in the context of almost universal falls in birth rates it is hard to work out which are the most effective. Bhattacharya says the best evidence suggests that cash subsidies work. “You are going to have to throw a lot of money at it.” Britain does pay child benefit to most parents (it tapers off once at least one parent earns more than £60,000) but it is spread over the whole of childhood.

Phoebe Arslanagić-Little, who is head of social research at the Onward think-tank and has founded a campaign called Boom that wants to “make choosing to have children easier, for everyone” – she rejects the description “pro-natalist” – thinks it would be better to front-load the benefit to reflect the expense of childcare.

She dismisses the idea that the climate crisis and a degree of nihilism about the future of the world is making people less likely to have children. “Overwhelmingly, the thing that influences whether a person has children is their personal circumstances… The greatest demographic change in modern history, the baby boom, began in the late 1930s. I don’t think we are living in a uniquely bad world. It’s important to say that.”

And while childcare and housing costs have gone up, so has the amount of free childcare available. Fifteen years ago, only a fifth of mothers of small children worked full-time. Now 39% do. Working from home has transformed many parents’ ability to earn money.

Britons rightly feel their standard of living has not improved for nearly two decades, especially if they are paying off student loans and struggling to afford a place to live, but the fact that birth rates have fallen all over the world suggests that money is not the sole explanation.

For Bhattacharya, the problem is that society does not value people who look after children, just as it dismisses social care as low-skilled work. “That’s the political shift we ought to be making. It’s a longstanding feminist critique that its value is not adequately recognised, and we shouldn’t be surprised that when it’s not recognised, people choose not to do it.”

As children spend more time indoors, families get smaller and relatives live further away, parenting is largely done alone. But the result is that maternity leave can be a uniquely isolated and exhausted time, when women’s income plummets and the freedom they used to enjoy comes to an abrupt end. Nor is there much indication that men are ready or able to share the burden. Shared parental leave became available more than a decade ago. Fewer than one in 50 fathers take it up.

And perhaps there is another explanation, one that we might not want to confront. Was it in fact scarcity, disease and the fear of being abandoned in old age that led us to have plenty of children – as well as the fact that there was no reliable way of stopping them?

Since we broke the link between sex and reproduction and offered men and women the same opportunities, humans have an urgent question to answer. What if, as life gets better, our urge to reproduce is fading away? The concept of pro-natalism makes many people wince. But they will be hearing a lot more about it.

Ros Taylor hosts the More Jam Tomorrow and Oh God, What Now? podcasts