It was supposed to be a routine, albeit clandestine, flight. On January 21, 1968, a US B-52 bomber, call sign HOBO-28, laden with four nuclear warheads, was in a holding pattern over the Thule airbase in northwest Greenland, deep in the Arctic Circle, when one of the crew members smelled burning rubber.

Foam cushions placed over a heating vent had caught fire. The crew desperately tried to extinguish the blaze, but it quickly became uncontrollable. They radioed down to the Thule airbase, the US’s most northerly military installation, for permission to make an emergency landing. But it was too late. The cockpit filled with smoke. The plane lost electrical power.

Six of the crew were able to parachute to safety; the seventh sustained fatal head injuries as he attempted to bail out. The pilotless bomber careened into the sea ice of Wolstenholme Fjord at 900km/h. When the bombs hit the ground, the conventional explosives detonated on impact, but there was no nuclear explosion. Even so, radioactive material was scattered across 30 square miles, and there was heavy plutonium contamination.

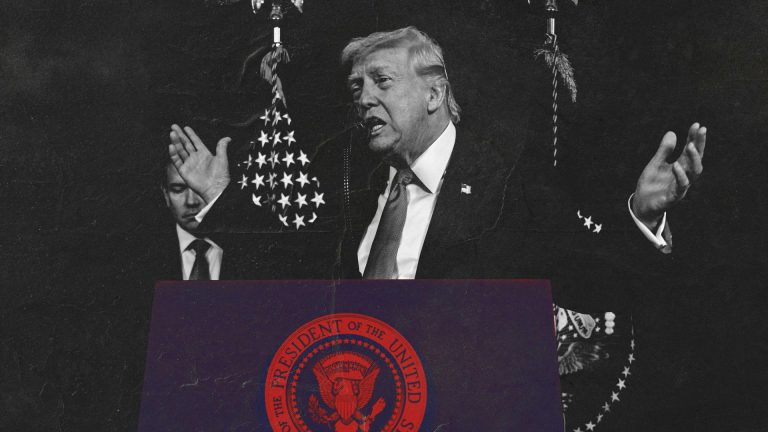

The crash left a scar gauged into the ice 700 metres long and 160 metres wide. It is a wound that is yet to fully heal, and that has ramifications for the complex three-way relationship between America, Denmark and Greenland that exists to this day. Donald Trump has made clear, once again, that he has ambitions to absorb Greenland. Speaking in the first week of January, Trump told reporters: “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security”. After the strike against Venezuela to the south, the chances that the US will make a move in the north now look all the more plausible.

Suggested Reading

The lesson of Maduro’s abduction: Europe must unite, or die

The US first established a military presence in Greenland during the Second

World War, when the Danish ambassador to the US, Henrik Kauffmann, asked Washington to protect its colonies following the Nazi invasion of Denmark 1940.

Greenland, effectively a midpoint between the northern US and northern Russia, became even more strategically important for the US during the cold war. “It was the place that you could get closest to the Soviet Union with a nuclear bomber,” says Ulrik Pram Gad, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute of International Studies. By permitting the base, Denmark “proved its value as an ally to the US”.

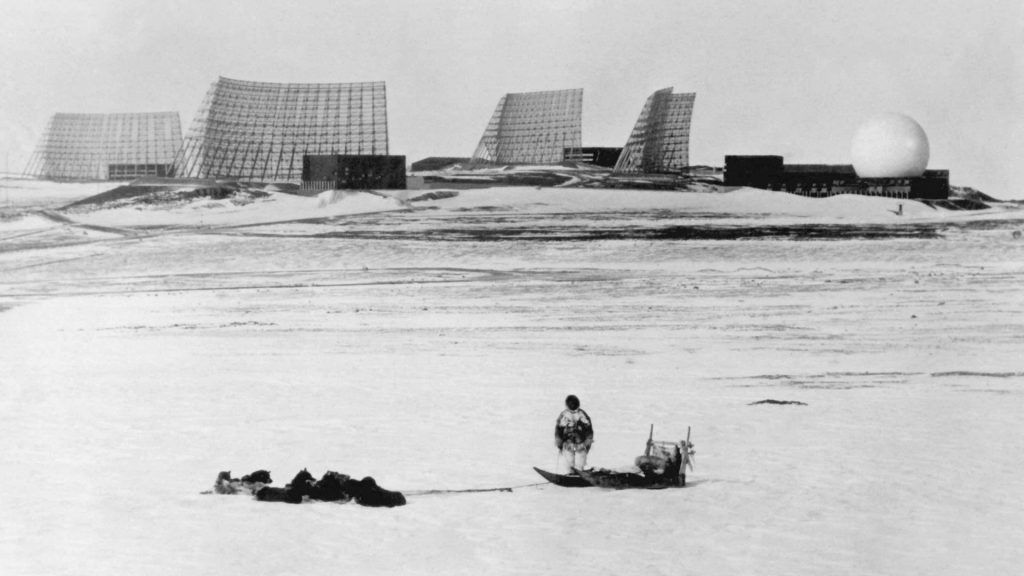

In 1951, the two countries signed a treaty allowing the US to build the Thule Air Base. Completed two years later, it is 750 miles north of the Arctic Circle, in northwest Greenland. Ice-locked for nine months of the year, when it is only accessible by air, the base once housed 10,000 military personnel.

Renamed Pituffik in 2023, it is now home to less than 1,000 servicepeople, but its “top-of-the-world” location makes it an ideal place to situate an early warning radar weapon system.

The agreement to establish the base was made exclusively between Washington and Copenhagen. No politicians from Greenland were involved and there was no consideration given to the local Inughuit peoples, who were most directly affected. The base interfered with their hunting grounds and to make room for it, 26 households totalling 166 people were forcibly resettled around 65 miles north in Qaanaaq.

This took place less than two weeks before Greenland won autonomy from Denmark. At any point after that, a forced population move of this kind would no longer have been possible.

The HOBO-28 mission was part of Chrome Dome, a secret US military operation in which B-52 bombers with nuclear payloads stayed continuously airborne and on alert. There were various routes, one over north America, one over Europe. The Chrome Dome flights followed a figure-of-eight pattern over Thule, which meant the US could launch a retaliatory strike even if the base was destroyed.

The B-52 crash site was around seven miles from the base. First on the scene was a small group of Inughuit hunters. Then came hundreds of US military personnel and Danish support staff from the base. In the permanent darkness of the arctic winter, and in temperatures as low as -60C, they set about retrieving fragments of the destroyed aircraft plus tonnes of contaminated snow and ice.

The revelation that the US had been routinely flying nuclear-armed planes over Greenland severely strained its relationship with Denmark, which had declared itself a nuclear-free zone in 1957. This meant Danish law effectively prohibited the presence of any such weapons on any of its territories.

However, in 1995, it was revealed that the prime minister at the time, HC Hansen, had sent an ambiguously worded, handwritten note to the US ambassador that gave tacit approval for this to happen.

As one State Department official put it, this meant the US could do “almost anything, literally, that we want to in Greenland.” From 1958-65, the US housed at least 48 nuclear warheads at Thule.

Knowledge of the base and its nuclear function became an open secret. “Everybody with some specialism in academia, or military affairs or international relations knew,” said Gad. “Also, there were thousands of Danish workers at the base, and it was clear to them that it housed nukes. It was more a case that it was a very secluded place that was mentally not a part of Denmark, and in a sense not even a part of Greenland.”

It was one of a string of revelations that emerged after the crash. Danes and Greenlanders involved in the clean-up also claimed that exposure to radiation led to problems including premature ageing, extreme fatigue, undiagnosed skin diseases, and immune system deficiencies. Official investigations found no link, and even concluded that the problems were caused by the men’s lifestyles.

Despite the clean-up operation, a BBC report in 2008 claimed that one of the bombs had broken through the ice and sank to the sea bed, and that a submarine rescue operation failed to recover it. When US analysts examined the retrieved bomb parts, they found one of the secondary charges was missing. Experts believe the lost bomb poses no threat to inhabitants or the environment. Even so, there is a high likelihood that a substantial amount of US weapons-grade nuclear material remains lost somewhere on the seabed under the ice off North Star Bay, in northwest Greenland.

The most enduring controversy stems from the eviction of the Inughuit people, which only became public knowledge in the 1980s. In 2003, a small amount of compensation and an apology were issued by the Danish prime minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen.

“There are people alive today who cannot go back to where their ancestors came from,” says Gad. “Also, it’s a nomadic hunting community and the base dissects their hunting grounds, and they have to be afraid that it’s radioactive.”

Over the subsequent decades, the forced resettlement has become a central component in debates over Greenlandic autonomy, as it casts Denmark as callous imperialists.

It is also seen by Greenlanders as indicative of their wider maltreatment by Danish colonisers, an issue that continues to cast a long, dark shadow over relations between the two countries. “Parenting competence” tests on people with Greenlandic backgrounds were only banned in May 2025 after a years-long fight by campaigners and human rights bodies who argued that they were racist.

In September, the Danish PM Mette Frederiksen formally apologised for historic injustices against Greenlanders and proposed a reconciliation fund to compensate those affected. It includes approximately 4,500 women, some as young as 12 at the time, who were fitted with intrauterine devices without their knowledge or consent in the 1960s by Danish doctors in an attempt to reduce the population of Greenland. The island’s former prime minister Múte B Egede condemned the policy as “genocide”.

With recent polls suggesting almost 80% of Greenlanders back independence from Denmark, some see Frederiksen’s efforts as a cynical attempt to strengthen relationships between the two countries, but Gad believes they are genuine. “She’s been the prime minister who’s been most open to historical reconciliation and constitutional reforms giving Greenland more independence.

“I think she would have liked to move on earlier, but Covid came in the way, Ukraine came in the way; it’s only been pushed to the top of the agenda by Donald Trump. All the goodwill she was trying to show seems a bit too little, too late, so it’s difficult for Greenlanders to accept it with the goodwill they would have done a couple of years ago.”

The base returned to headlines in 2025, when the Thule base welcomed the US vice president JD Vance. The controversial visit underscored the strategic importance of both the base and Greenland. It was of importance in the fight against the Nazis, then the Soviet Union. But will Greenland now have to fend off another aggressor state, one that already has a military presence on its territory, one that, until recently, it regarded as a friend?