On December 4 1972, Chile’s socialist president, Salvador Allende, addressed the United Nations. The US authorities pointed out that, even though Allende was at UN headquarters in New York City, he was not officially visiting the US. It was a sign of the White House’s intense disdain for Allende. In the eyes of US president Richard Nixon, he was already a non-person.

Before Allende, the most celebrated left wing Latin American leader to address the UN was Fidel Castro, who spoke for four-and-a-half hours. But there was little danger of the bespectacled intellectual Allende haranguing anyone. Instead, over the course of 90 minutes, he explained how American mining firms had drained Chile of its most valuable resources – principally copper.

“More than 80% of our exports [are] in the hands of a small group of large foreign companies that have always put their interests ahead of those of the countries where they make their profits.” Muffled applause drifted across the assembly.

“These same firms exploited Chilean copper for many years, made more than $4bn in profit in the last 52 years alone, while their initial investments were less than $30m… We find ourselves opposed by forces that operate in the shadows without a flag, with powerful weapons from positions of great influence,” Allende said, before coming to his sharpest ideological point. “We are potentially rich countries, yet we live in poverty. We go here and there, begging for credits and aid, yet we are great exporters of capital. It is a classic paradox of the capitalist economic system.”

The president humbly accepted a standing ovation, one peppered with cries of “Viva Allende!” from Latin American delegates. Even the US ambassador to the UN, George HW Bush, saluted the speaker. In a dark irony, Bush would later go on to run the CIA – the very organisation that was, at the time, working to destroy Allende’s government. In the end, the CIA would succeed.

The public life of Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens spanned four decades. Born into an upper-middle-class family in Santiago in 1908, his early passions were football and medicine, and as a student he developed a strong belief in the necessity of socialised medicine, which was considered outrageous at the time.

In 1931, he was expelled from medical school. There would be further trouble after Allende completed his training and took up a position at Santiago’s Van Buren hospital. As leader of a physicians’ union, he fell out with the authorities and even briefly wound up in prison.

Suggested Reading

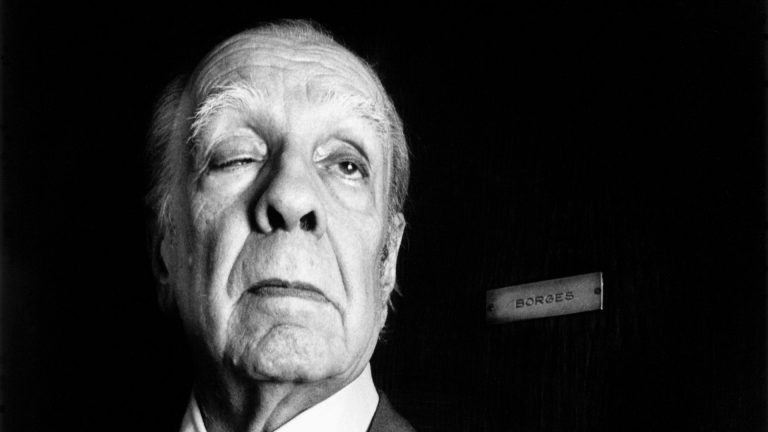

Jorge Luis Borges, a doppelganger in Buenos Aires

From the late 1930s onwards, he worked his way up on the Chilean left, and held government posts including health minister. He first ran for president in 1952, and lost, but further defeats in 1958 and 1964 did nothing to dampen his conviction that socialist ideas could propel Chile forwards.

Allende finally won the presidency in 1970, promising “the Chilean path to socialism”. The US immediately registered his administration as a profound ideological threat and the effort to destabilise and remove him began. Six weeks into his tenure, the Chilean general René Schneider was shot and killed in a botched kidnapping attempt in Santiago. Schneider was head of the army and had refused to participate in a CIA-sponsored attempt to oust Allende. He was succeeded as head of the army by general Carlos Prats, who was killed in Buenos Aires by a car bomb so powerful that it sent debris up to the ninth-floor balconies of the surrounding apartment blocks.

Allende’s political view was that capitalism could be ended peacefully in Chile. But his decision to nationalise the holdings of US corporations, along with his political affinity for the Soviet Union, were too much for the Nixon White House, which was embroiled in the worsening anti-communist conflict in Vietnam. Another Marxist government could not be allowed to take hold, especially not in the US’s own “back yard”. Nixon, along with secretary of state Henry Kissinger, dedicated a secret budget of millions to getting rid of Allende.

The beginning of the end came in June 1973, when a tank commander surrounded the presidential palace and demanded that Allende leave. In August there was a constitutional crisis brought about by a political challenge to Allende in the courts, followed in September by the final coup, which was led by the new commander of the Chilean military, general Augusto Pinochet.

Just as he had used the power of rhetoric at the UN, as the military closed in Allende gave a live radio broadcast. Unlike the other “traitors” of his government, he said, he had not fled from the presidential palace.

“I will not resign,” he told his fellow Chileans. “Foreign capital – imperialism united with reaction – created the climate for the army to break with long-held tradition. Long live Chile! Long live the people! These are my last words. I am sure that my sacrifice will not be in vain… it will at least be a moral lesson, and a rebuke to crime, cowardice and treason.”

There is some uncertainty about exactly how it happened, but it seems that Allende took up a rifle and shot himself. The coup leaders arrived and his body was taken to hospital that evening, where it was examined by one of Allende’s former colleagues from his student days at medical school.

The firearm that Allende had apparently used was an AK-47. It had a gold plate embedded in the stock, bearing the inscription, “To my good friend Salvador Allende from Fidel Castro”. But now he was gone – and the authoritarian Pinochet was in charge.