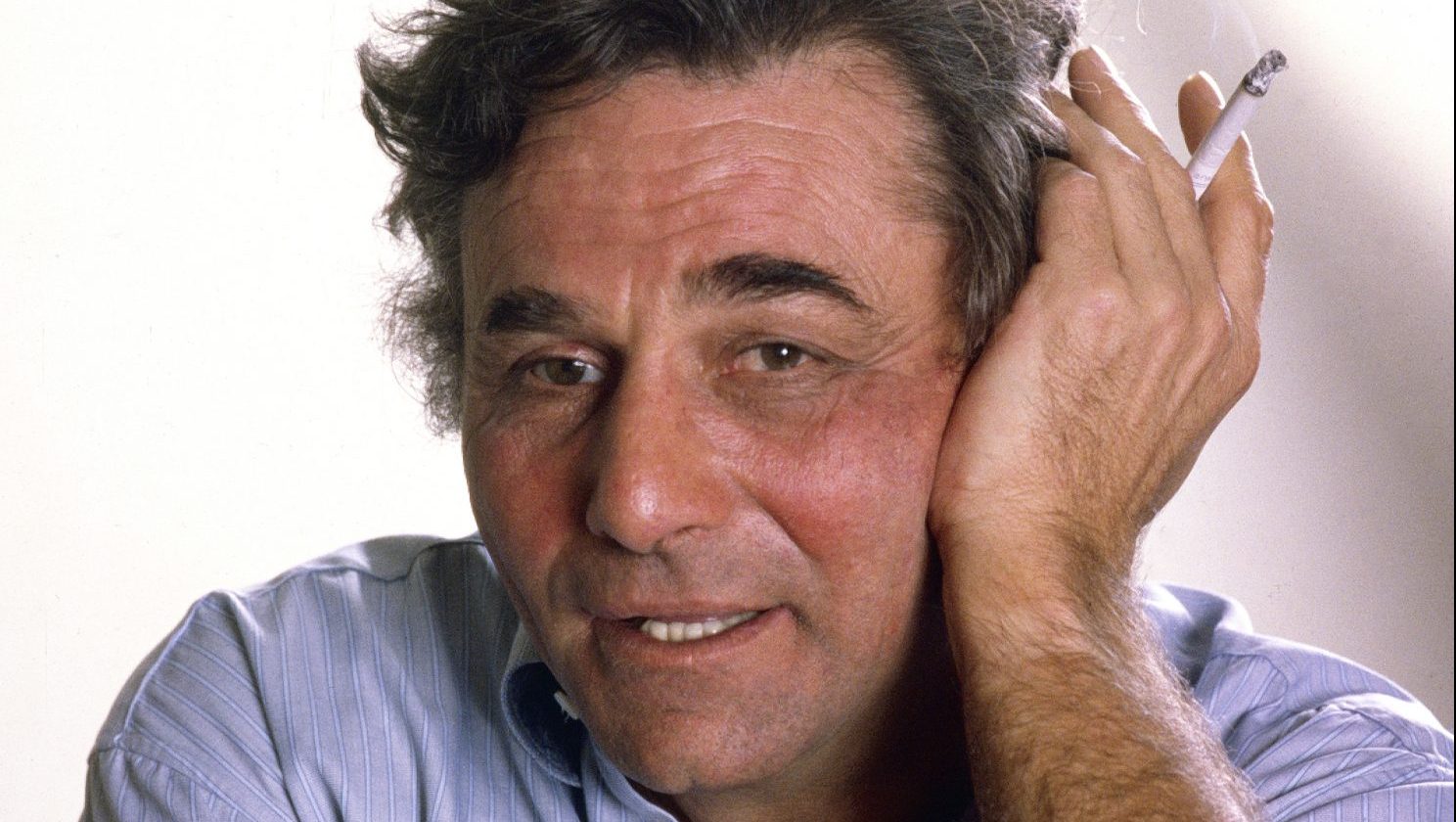

Nicolae Ceaușescu looked at the screen and grinned. On it was a rumpled face familiar worldwide, and especially cherished by the dictator, a communist critic of American culture who was a secret devotee of American television, especially cop shows.

Cherished too by those under the grip of Ceaușescu, who for very fathomable reasons felt a deep connection with the character played – a little man who picked apart the schemes and dreams of the rich, powerful and murderously corrupt. And who would have been delighted when they turned on their televisions one night in 1974 and saw him talking directly to them.

“Oh, excuse me – do you have a minute?” he said. “I’m Lieutenant Columbo. Sometimes I’m known as Peter Falk. When an actor plays a role, he hopes he’s creating a character the audience can identify with. And from what we’ve heard about Romania’s acceptance of the Columbo show, well, I guess we must have been doing something right…

“We would like to thank Romanian television for putting us on the air on Saturday and Sundays. But most of all, we want to thank all the Romanian people for their great response to our show. We’ll be seeing you again next fall.” Then Peter Falk smiled and said, in Romanian: “Goodbye and good luck.”

Born in the Bronx in 1927, Peter Michael Falk had a lifelong affinity with the underdog. It made him a supporter of left wing causes, a trade union member and the kind of man who could be persuaded – by the US state department, no less – that he might improve detente by recording a personal message for the people of Romania, caught behind the iron curtain.

His own outsider status had been conferred on Falk at the age of just three, when he lost an eye to cancer. Devastating as this must have been, it didn’t prevent the young man from excelling at sport. When the family moved out of New York City and his father found work repairing prison uniforms in a large upstate facility, Peter found himself playing baseball against, and identifying with, the inmates.

His misfortune bred in him a fearlessness and restlessness. His missing eye prevented him from joining the navy but couldn’t stop him from signing up for the Merchant Marine. He travelled in Europe, laid railway tracks in the old Yugoslavia and, on return to the US, attempted to join the CIA but was rejected, a byproduct of his lapsed membership of the Merchant Marine’s radical union.

Suggested Reading

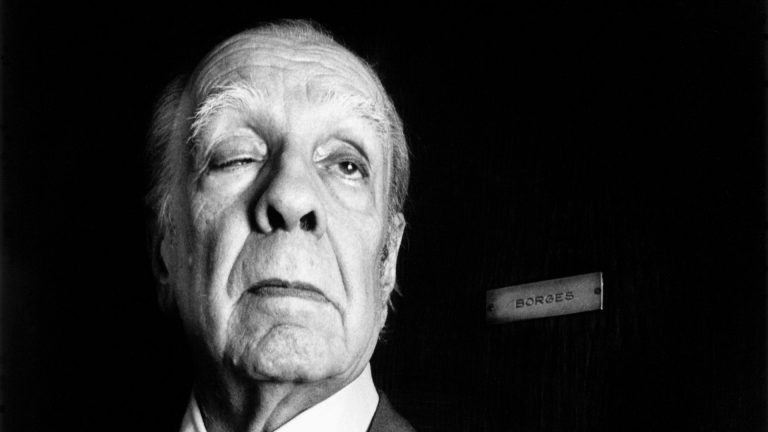

Jorge Luis Borges, a doppelganger in Buenos Aires

Though he’d acted in school productions – including as a detective – his talent bloomed late. He was 30 when he appeared on television for the first time, 33 when he made his movie breakthrough in Murder Inc, winning him a best supporting actor Oscar nomination and embarrassment when, at the ceremony, Falk saw the envelope opened, heard the name “Peter…” called and stood up, only for the presenter to complete the name “… Ustinov”.

Rather than the big-name producers and directors who feted him, Falk’s closest friend was John Cassavetes, first a rival actor who “took every job I wanted on TV” and later a director of remarkable independent films. Any list of Peter’s greatest movie performances is incomplete without mentioning Husbands (1970) or A Woman Under The Influence (1974), the latter that rare film where the leading man, Falk, so loved the script that he stumped up half the budget.

It was the Columbo money that made such generosity possible. Falk first played him in 1968, bringing his own raincoat to the role, along with his trademark squint and his belief that what makes the detective so appealing is the dogged determination beneath his dog-eared appearance, a quest to show that the everyman can be every bit as exacting and quick-witted as the wealthy man. The first full episode was directed by none other than Steven Spielberg, just a few years before his success with Jaws.

Away from Columbo, Falk had excellent comic turns in The Brink’s Job (1978), The In-Laws (1979) and… All The Marbles (1981) and impressed in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987) as an angel who chooses to live as a human. Wenders said: “When he wasn’t filming, Peter would go off into the corner and sketch people. I found that very touching and rather angelic. It was more proof that we’d found a former angel to play the part of a former angel.”

For most, the ultimate Peter Falk moment will always be a series of moments – the occasions when, apparently flummoxed by the careful plotting of one of his supposed betters, Lieutenant Columbo made to exit a room, then turned and announced: “Just one more thing…” But what sums him up best is possibly the greatest acceptance speech in the history of gong-giving, delivered when Falk was nominated for best actor at the 1972 Emmys – and this time, did hear his full name called.

“It’s terrific to win,” he began. “I’m trying to figure out some way to appear humble… It’s not going to work.

“I was in New York yesterday… I had some business in the morning, I did some shows. Then I grabbed a cab and I raced to the airport trying to catch the 11 o’clock. I figured I’d miss it, and I did. So I laid over in Kennedy for three hours to catch an Eastern out to Atlanta. I was there for two hours, then caught a Delta into Dallas. I was two hours there to get a TWA into LA…

“Look, I know it’s not a very interesting story (huge laugh). I only mention it because I wanted to point out that, in regard to whether or not I wanted to be here, I was relatively indifferent.”