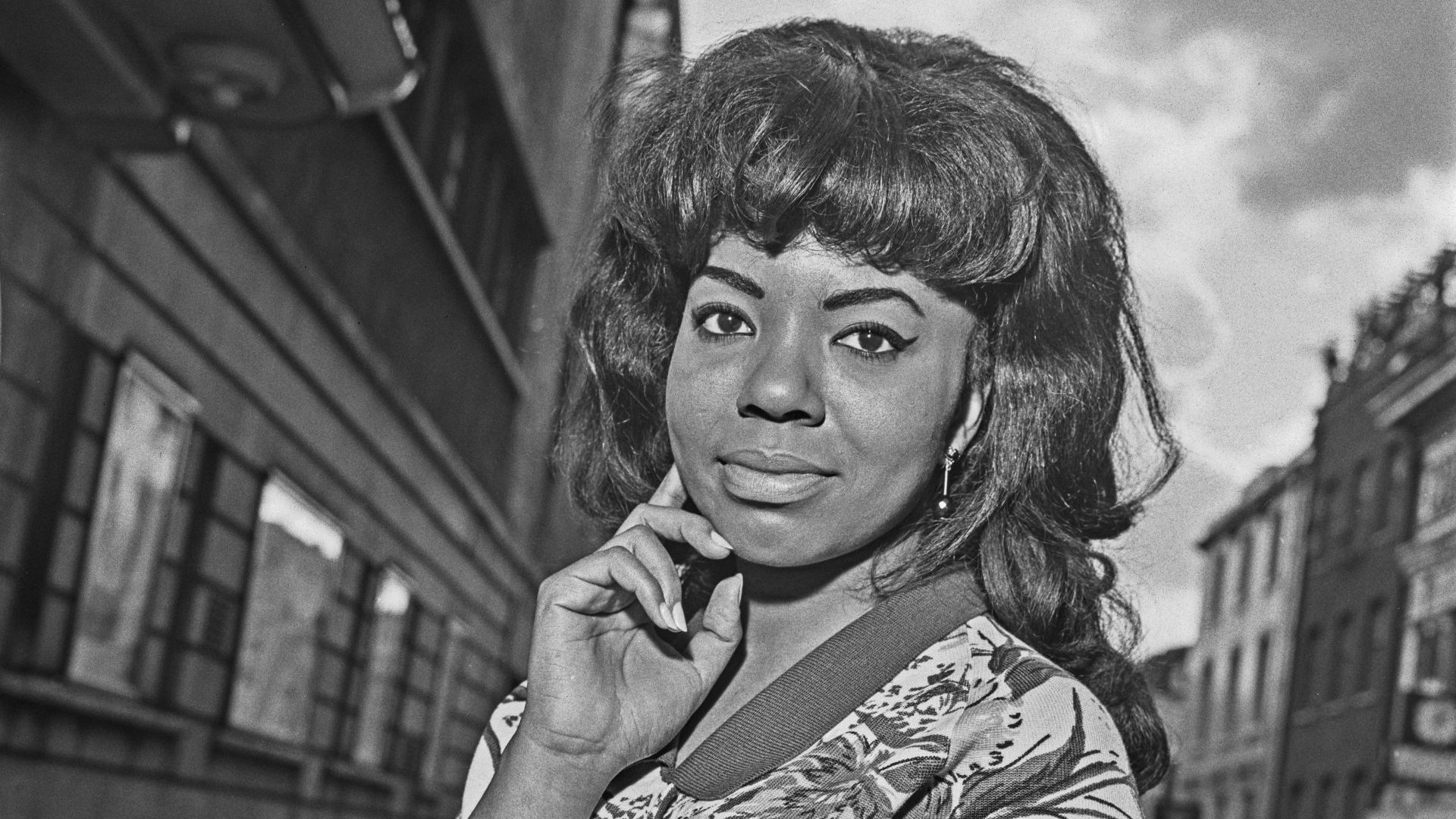

Mary Wells would not take no for an answer. Having turned up at Detroit’s 20 Grand nightclub with a song in her pocket, the man she’d arranged to meet told her he was too busy to hear it. But, she said later, “I was persistent.”

So, as he walked away down the corridor, she stayed in lockstep close behind him until he turned and ordered her to “sing it right now”. Mary did. A day later, on July 8, 1960, she was signing a recording contract in a scruffy two-storey house close to her home that would soon have a sign on its wall boasting that here was “Hitsville, USA”.

Having impressed Berry Gordy with her song and her determination, Mary Wells was now a Motown recording artist. By September, the song Bye Bye Baby was in the charts and both its singer and her label were at the start of a dizzying rise.

If the story suggests that Mary Wells’s life was as joyous and effortless as her most memorable recordings, nothing could be further from the truth. Born in the self-styled “Motor City” in 1943, her childhood was marked by crushing poverty and near-fatal cases of meningitis and tuberculosis.

Her real father may have been a white man of Italian heritage; her black stepfather was distant and frequently absent. Her own choices of partner were often unwise, as were her many of her business decisions. She chain-smoked cigarettes from an early age, contributing to the throat cancer that would end up silencing her for ever. There were affairs and lawsuits, suicide attempts and violence, including – at the height of her fame – an incident in a Manhattan hotel suite in which her ex-husband shot Wells’s would-be manager through the eye while she cowered in the bathroom. Astonishingly, the man survived and no charges were brought.

Wells was part of the huge cultural shift that brought black music to the attention of white audiences across the world. Her Motown career came to life when she was paired with Smokey Robinson, who, when he wasn’t recording smash-hit records, was busy writing for Gordy’s other artists.

A trio of top 10 hits in 1962 eventually led to the recording of the simple, sweet and timeless My Guy, which topped the US charts and reached No 5 in the UK. It would be a lesser song without the stuttering coda Wells added in the studio. More hits followed, in collaboration with Marvin Gaye.

Suggested Reading

Louis Armstrong, the man who spread jazz’s gospel around the world

And then, and at the peak of her success, Mary Wells left the most famous soul label in music history, the one Gordy was now billing as “the sound of young America”. In doing so, she displayed all the self-belief and determination that she had shown that day at the 20 Grand.

The problem was that Mary, despite being nicknamed “the queen of Motown”, was still on the contract she’d signed as an unknown 17-year-old, and was outraged to hear that her royalties from My Guy were being spent not on her next album but on Gordy’s new next big thing – the Supremes.

After accepting a one-time payoff of $30,000, Wells joined 20th Century Fox’s fledgling record label for a signing-on fee of $200,000 – a combined £2m in today’s money. What she no longer had was Gordy’s ear for a hit, or songwriters like Robinson on call. She never again had a top 20 hit on the US Billboard charts.

Mary largely retired from recording in 1974, dedicating herself instead to new loves beyond music. There were her children (she had three with singer Cecil Womack and one with his brother Curtis) and there was also heroin, which helped her deal with the misery of her financial affairs.

That Motown payoff had required her to sign away the rights to all future royalties from her time with the company, meaning that the future riches to be made from compilations, from licensing for TV and films and from new formats like CD, eluded her. In the last active years of her career Wells lived on the money made from frequent gigging on the soul nostalgia circuit, where despite the drink and drugs (she also used cocaine and methadone), she remained in strong voice.

Then, cruelly, she was diagnosed with throat cancer. Told that the best course of action would be to remove her vocal cords, she accused doctors of planning to “cut them out and give them to a white girl” who couldn’t sing. She went on to lobby against cuts in the federal cancer research budget, telling Congress in whispered but spellbinding testimony: “I’m here today to urge you to keep the faith. I can’t cheer you on with all my voice, but I can encourage, and I pray to motivate you with all my heart and soul and whispers.”

While her family and management lobbied Gordy to rip up Mary’s 1964 exit deal, former labelmates Diana Ross, Mary Wilson and Martha Reeves, plus musicians like Bruce Springsteen, collected $150,000 for her medical bills. Gordy, who had made millions from Mary Wells, chipped in £25,000.

Accounts differ about what else he paid Mary before she died; it may have been as little as $60,000 or as much as $1m. Wells herself claimed he owed her $10m, the equivalent of around £18m today. Gordy also paid for her funeral, at which he was castigated in barely couched terms by Little Richard.

She might have been taken by cancer, but like the girl in the song, Mary Wells cannot really be kept away from us. She was persistent, and she will persist.