November 2006 and in front of an audience at New York’s 92nd Street Y, Gore Vidal is on a roll. In the crosshairs this evening is an old foe, Truman Capote.

“The last time I was here, I was afflicted by a fly,” Vidal informs the rapt audience. “It was an awful fly. Every time I started to speak, it buzzed. And I kept [swatting at] it and missing it.

“And then… do you remember that movie The Fly where that little voice comes out begging ‘Help me! Help me!’? Well, that’s when I realised it was the late Truman Capote come back to taunt me!”

The fact that Capote had then been dead for over two decades didn’t matter to Vidal, who relished a feud. William F Buckley, Norman Mailer, Bobby Kennedy, pretty much anyone who had the temerity to write while he still drew breath – he loved, even lived for, verbal jousting.

If the situation with Capote was on a different level to most of his spats, it was because Truman had opened the door on one of Vidal’s other lives, that of the political heavyweight who just happened to be Jackie Kennedy’s half-brother.

It was an area from which Capote was largely although not entirely excluded. As Vidal famously wrote, “Truman Capote has tried, with some success, to get into a world that I have tried, with some success, to get out of.”

Gore had little good to say about Camelot, but he wasn’t one to ignore a slight. So when Capote gossiped to Playgirl magazine about his rival having been kicked out of a Kennedy family party, the author of acclaimed historical novels like Burr, Lincoln and The Golden Age issued a writ with speed similar to that with which he dispensed bon mots.

Though he won the case, Vidal didn’t receive the million-dollar windfall he sought; Capote having run out of money just as he had run out of friends. Still, those who knew him said they’d rarely seen Gore happier. It wasn’t the prize that mattered to Gore Vidal – it was the winning.

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal spent a lot of his life winning. What defeats there were came at the ballot box – he unsuccessfully ran for both the Senate and the House of Representatives – or in the domain of romance.

Vidal had relationships with actresses Joanne Woodward (later to marry Paul Newman) and Diana Lynn, and perhaps with writer Anaïs Nin. But he also claimed to have slept with Fred Astaire and Dennis Hopper and spent 53 years with writer Howard Austen. The love of his life, though, was probably boyhood friend James Trimble III, who died at Iwo Jima.

Suggested Reading

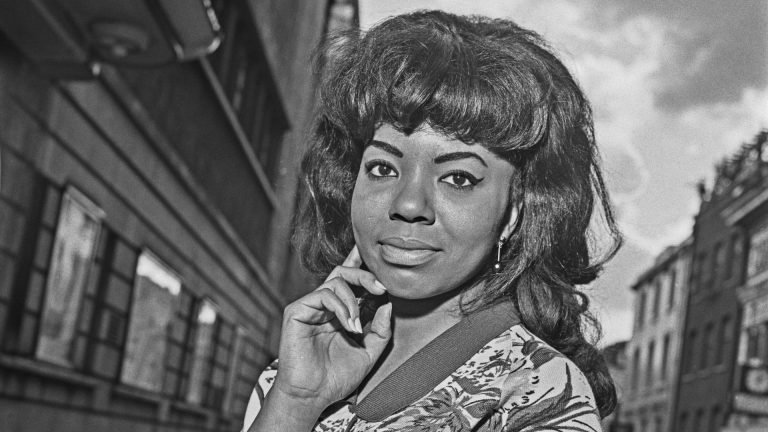

Mary Wells: The Queen of Motown who renounced her throne

Such were the circles Vidal walked in, even youthful tragedies had an epic dimension. If losing his mother to alcoholism was one thing, it was nothing compared to how upset he was when his father, Bureau of Air Commerce director Eugene Vidal Sr, failed to wed the love of his life, the pioneering Amelia Earhart.

The grandson of Senator Thomas Gore, no one was surprised that politics ate up so much of Vidal’s life. More of a shock was his fascination with – and his success in – as low-rent an art form as screenwriting.

With 40 pictures to his name, it’s rather ironic that he didn’t receive credit for his most significant work, the script for William Wyler’s Oscar-hogging remake of Ben-Hur. With the fee erasing whatever pain this oversight might have caused, Gore also wrote for the stage. The Best Man – his play about a political convention – has been regularly revived on and off-Broadway.

The Best Man was also adapted – by Vidal, naturally – for the cinema. Alas, the same can’t be said for Myra Breckinridge, the infamous satire that was turned into an unwatchable film starring Raquel Welch as a transgender woman.

Gore dedicated the last four decades of his life to avoiding both the picture and any discussion of it, although being a great gossip, he cheerfully described it as “the second worst film ever made.” In case you’re wondering, Gore thought the worst film ever made was Tinto Brass’s Caligula, the script for which was written by one G Vidal.

Far more respectable was Vidal’s literary output, consisting as it did of weighty and stylish books about everything from the Roman Empire to contemporary politics, together with epic historical fiction. There were also compelling semi-autobiographical works such as The City and the Pillar – one of the first mainstream books to freely discuss homosexuality, dedicated to Trimble – not to mention several essays and short stories. On his death, Vidal was hailed as a great and pioneering American writer.

What Vidal was perhaps best at, though, was being himself. An unashamed member of the educated liberal elite in the days when small-town America might be charmed and amused by such people rather than reaching for the nearest pitchfork, he parlayed his wit and access into a career of TV interviews, speaking engagements and debates.

He portrayed animated versions of himself in The Simpsons and Family Guy and more or less played himself in Tim Robbins’ hugely prescient Bob Roberts (1992), in which his self-satisfied incumbent Democratic senator is swept aside by an aggressive and duplicitous young populist. It was in keeping with his view of himself as the last member of a dying breed.

When Vidal died in 2012, it was the alcohol that had undone Gore’s mother that also finished him. As many took glee in pointing out, the bottle – combined with narcotic excess – had also beaten his rival Truman Capote.

Still, if there was a baron of bad taste, that title surely belonged to Gore Vidal. For what was his response on learning of Capote’s passing? “Good career move.”